The online edition of Metropolis magazine recently featured an article I wrote on the work of N.C. State’s Coastal Dynamics Design Lab, an active, outreach element from the College of Design. The group has helped more than 30 communities across the state of North Carolina recover from flooding and hurricanes, rebuild to withstand future catastrophes and play to their strengths with culture, history and natural assets for economic development. A+A is pleased to repost it today:

Established in 2013 by architect David Hill and landscape architect Andrew Fox, a team of six landscape architects from the Coastal Dynamics Design Lab (CDDL) at the NC State University College of Design help communities rebound from storm damage—and plan for resilience.

So far, the CDDL has helped over 30 towns—from the Smoky Mountains to the coastal plains. North Carolina is a state crisscrossed with rivers and communities that were built along the waterways, which were once the primary mode of transportation and commerce. “Over time, development moved from limited high ground into lower-lying areas vulnerable to the natural cycles of flooding associated with these ecosystems,” Fox says.

Today, the state is increasingly affected by heavy downfall from slower-moving hurricanes and tropical storms. Post-flooding, the CDDL steps up to analyze a community, help it recover, and create a plan for resilience. “Our work helps a town reimagine what its lands can be, whether park space or restored back to a flood plain with reforestation,” he says.

First, the lab meets with local politicians, staff, and citizens to assess damage and resources. It drafts short-term rebuilding strategies, and long-term resiliency planning for recovery. Then it creates a floodprint—an in-depth analysis and step-by-step plan designed to mitigate damage from future storms.

It builds long-term relationships to create connections between needs and outcomes, and through funding, implementation, and management. “This form of ‘slow’ engagement and transformation fosters a deep trust between all partners, and that trust leads to a shared willingness to support change over time,” he says.

The lab operates on an annual budget of $600,000, covered by external grants and gifts (it does not charge the communities it serves) and writes grants to help communities rebuild—often using their own recreational, agricultural, and cultural resources as future economic recovery tools.

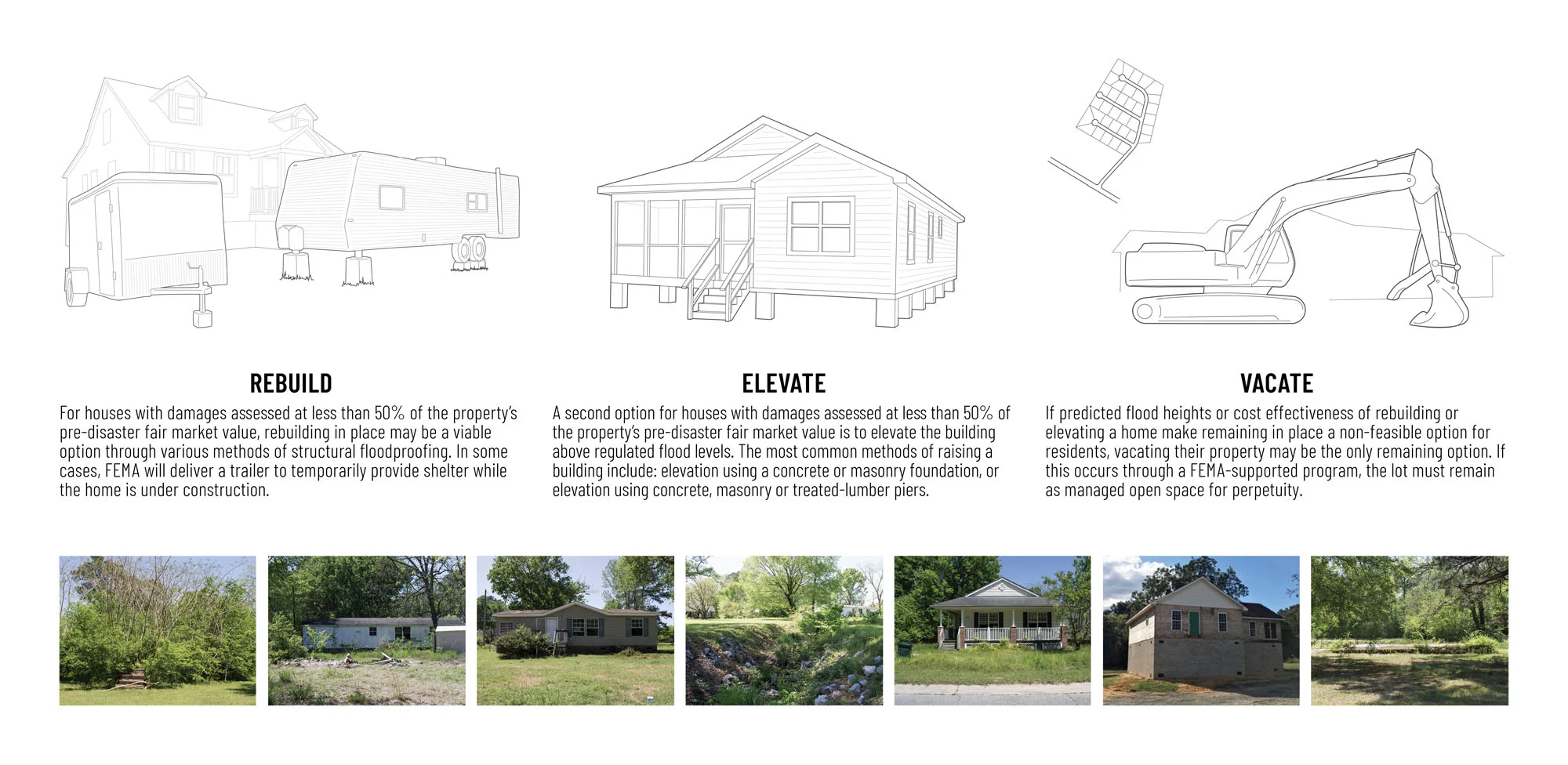

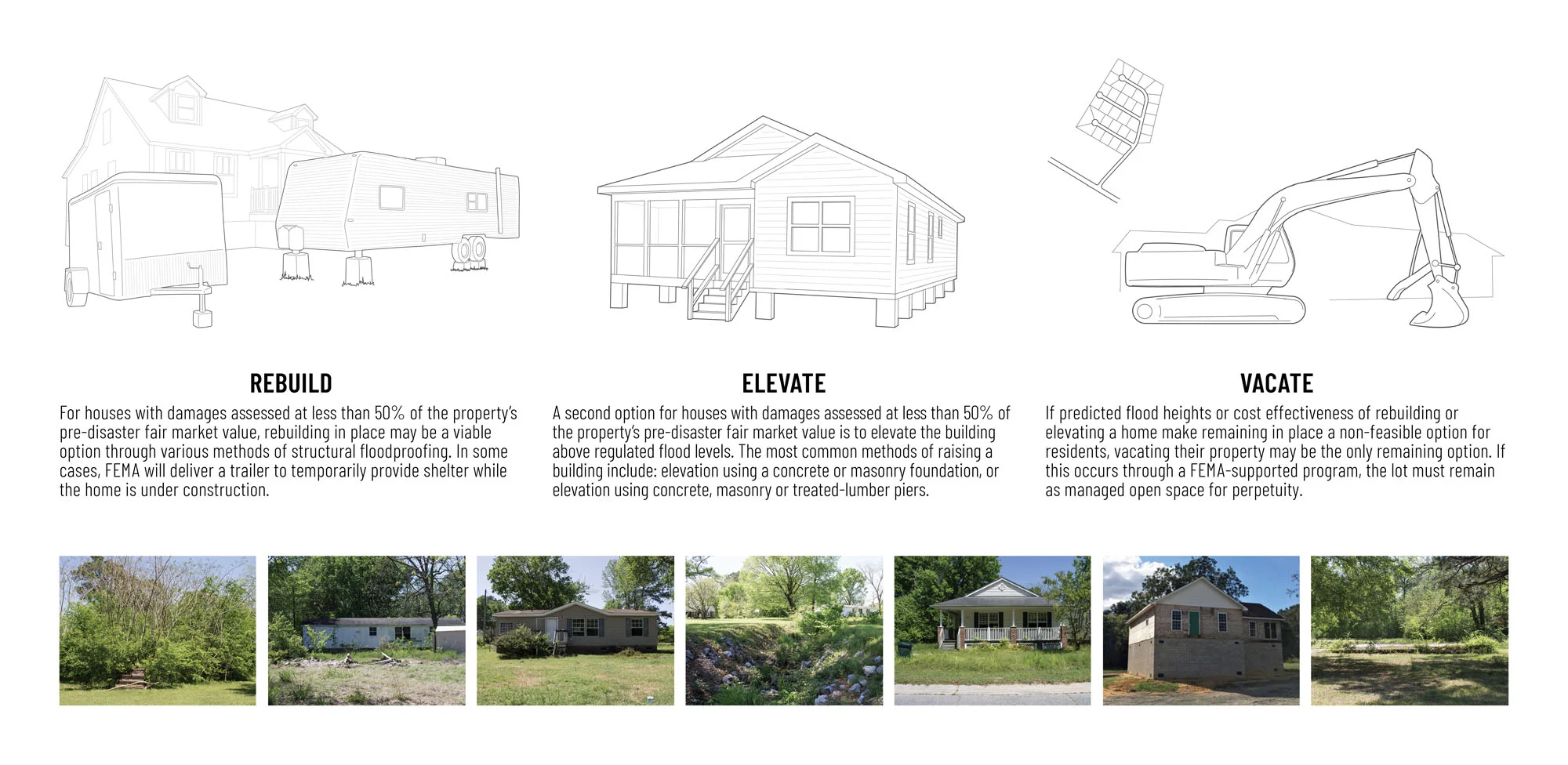

Its floodprints identify buildings in flood plains to be purchased by the state, then demolished, and replaced with rain gardens or open space. The hope is to keep people in town and contributing to the tax base.

“Residents can be safe,” explains Fox. “They can elevate, or sell and move to higher ground in town.” CDDL suggests other buildings that can be raised up above the base flooding elevation, out of harm’s way, offering solutions like redesigned riverfronts with bioretention areas and native plantings that soak up stormwater, which is then cleaned and slowly returned to the river.

Canton, a mountain town in Western North Carolina, suffered extensive damage from Tropical Storm Fred on August 17, 2021, when a 19-foot-high wall of water roared down the Pigeon River, killing six people.“It was like a bulldozer,” says David Francis,Haywood County’s director of community and economic development. “It channeled a new river.”

Canton lost one municipal building and a number of homes, in town and upriver. The lab is now studying how to mitigate future damage, and may write applications for FEMA grants to restore the town.

“We’re assessing flood damaged properties that could be designed to serve as both public open space and overflow areas,” Fox says. “Our goal in Canton is to integrate this work into larger economic development strategies.”

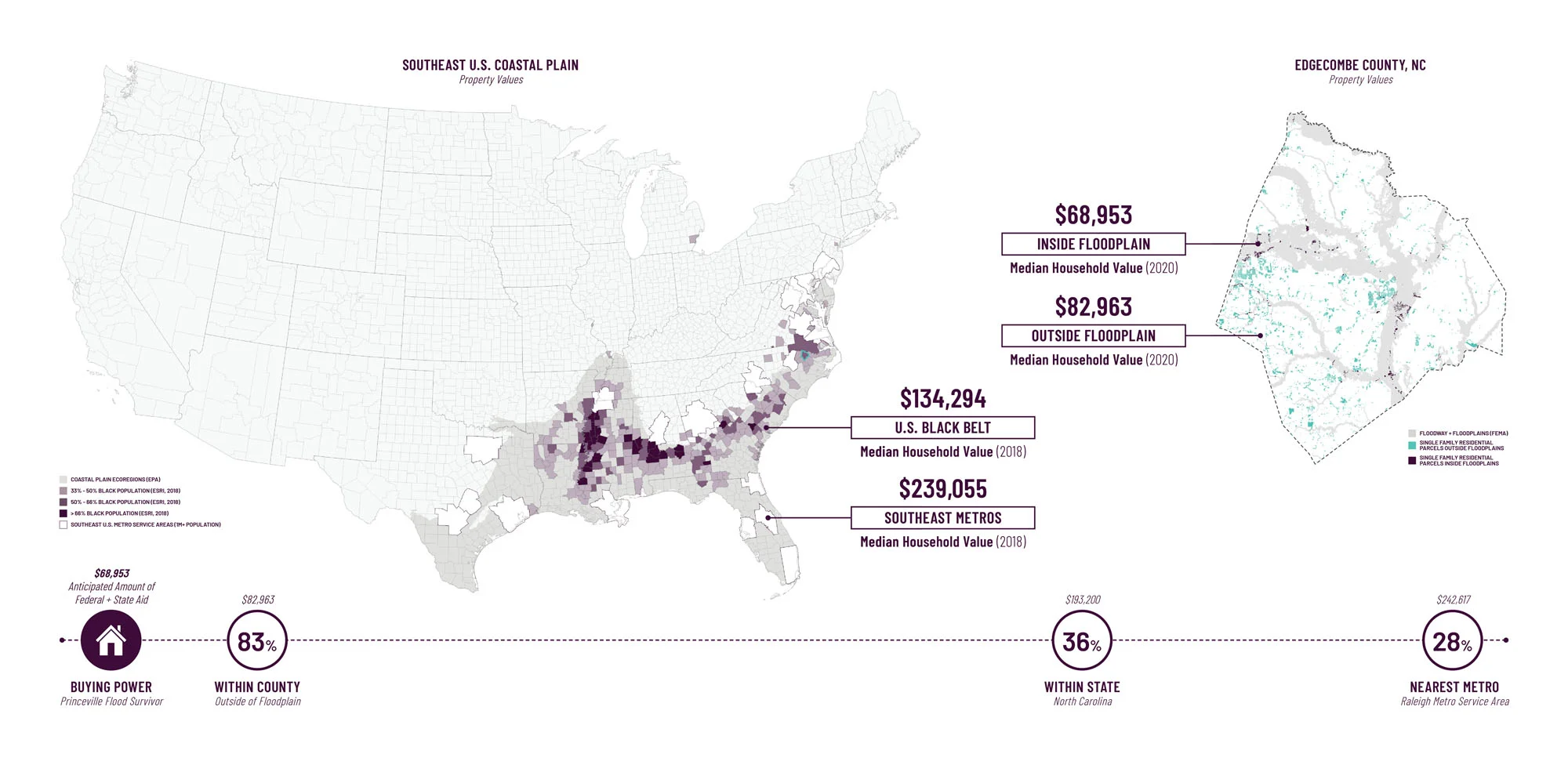

Princeville, a town with a population of 2,000 on the Tar River on North Carolina’s coastal plain, is recovering from flooding from two hurricanes. After Hurricane Floyd hit in 1999, the entire town had to be rebuilt. Matthew struck in 2016 with more flooding, but less destruction.

Still, a senior center had to be torn down and rebuilt; CDDL helped write a grant to build educational raingardens at the elementary school. Twenty-two homes in the floodplain were bought by the state, and replaced by community gardens. Three new homes have been built, with two more to come. “The lab is helping the people build back for themselves, and giving them inspiration,” says Bobby Jones, Princeville’s mayor.

The Princeville Mobile History Museum now celebrates Princeville’s status as “America’s oldest incorporated Black town.” Ellen Cassilly, is an architect and one of three NC State instructors

who ran a summer design/build studios at NC State for 13 years at the suggestion of David Hill, co-founder of CDDL and now head of NC State’s architecture department.

Fifteen students worked on the museum over the summer of 2019. “They went from conception to interviews, sketches, design, client design review, then more drawings, ordering materials, cutting steel and assembling the whole thing,” Cassilly says. “It was prefabricated in Raleigh and trucked down there— it’s trailer-based.”

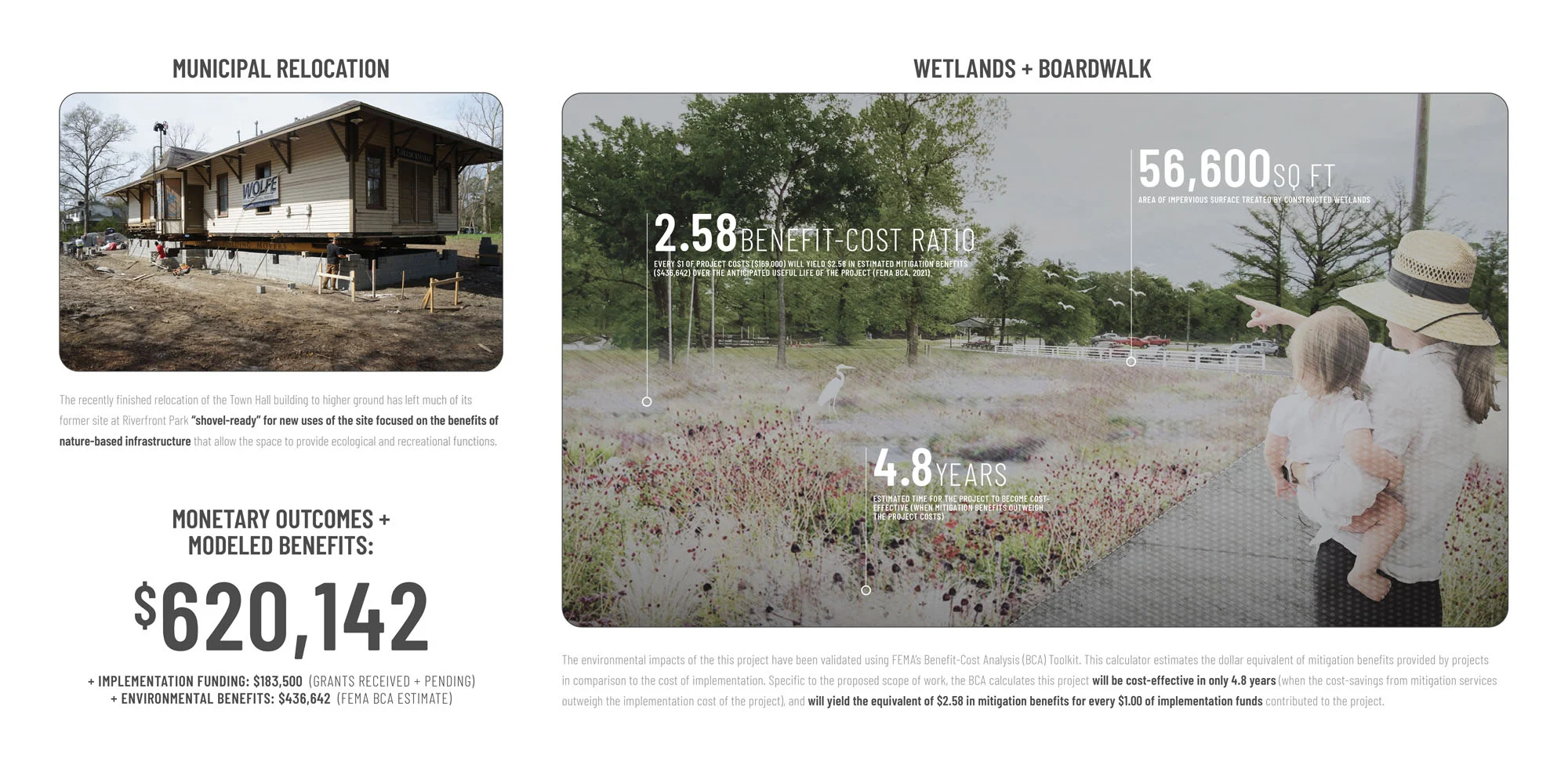

Pollocksville is a community of 275 people on the Trent River, in Eastern North Carolina. It suffered mightily from flooding during Hurricane Florence in August 2018, when the Neuse River backed up from New Bern into the Trent. On August 15, a ten-foot surge of water slammed upriver into town. Then three days of rain brought more water downriver, flooding the town and the bridge that leads into it.

The town has received $15 million in grants to recover and brace for future floods. Town Hall was moved away from the riverbank to higher ground, with almost an acre of bioretention areas now in its place—along with public boat ramps, benches, and kayak access. Some homes are being raised, while five others are eligible for state buyouts; open public space likely will take their place. New sidewalks, trees, and raingardens are planned for downtown.

The way Fox sees it, a town’s size doesn’t matter. “With great planning and strategic effort, the smallest of places can find a way forward,” he says.

His lab is a beacon that’s proving that every day.

For more, go here.