Joseph Giovannini is a practicing architect who’s written about architecture and design for more than 30 years as a critic for major newspapers and magazines, coast-to-coast. He has a new book out from Rizzoli called ‘Architecture Unbound: A Century of the Disruptive Avant-Garde,’ developed 20 years ago but put on the shelf after a conflict with publishers at Knopf. Thankfully, Giovannini and Rizzoli have granted the book a reprieve. A+A interviewed him last week by phone and email. Today’s post is the second of two based on those remarkable, insightful interviews:

Why choose chaos as the topic?

Chaos suggested the topic. I didn’t choose it. It was there to uncover and discover, and it led to many other subjects dealing with change, chance, uncertainty, and non-linear thinking and phenomena.

Philip Johnson’s reaction to your idea of Deconstructivism?

After I told him in the spring of 1987 that I was doing a book on an architecture of fragmentation and chaos, naming the principle architects, he called me at The Times about six months later and told me he was doing a show about the subject of my book. (Aaron Betsky had suggested a similar idea about fragments, so Philip had two critics.) Then he asked me what the title of the book was. I said, The Deconstructivists. After a pregnant pause, he said, “That’s it.” The term gave him themes on which he could develop a show: deconstruction and Constructivism, two influences coursing through some of the work. He asked me for names of other architects, which I did not give him. I did not tell him about other influences also coursing through the work, so his show was stuck in a limited understanding of the movement.

Knopf’s reaction to your book—and yours to them?

My editor at Knopf acknowledged that I had done a huge amount of work, but she asked me to put the 400 pages in chronological order. I had written it as a collage of progressive themes outside any chronology. There was, however, a throughline and logic that was cumulative. I felt she fundamentally misunderstood the movement if she thought I should put an architecture about non-linearity into a linear format. Besides, the influences were simultaneous and ongoing, and teasing out any linear sequence would have yielded a spurious understanding of the architecture.

Why pick up the book on disruptive avant-garde architecture again, after 20 years on the shelf?

Because it was too good to go unread. It had become history rather than current events. I just had to change the verbs from present to past tense. But it wasn’t as simple as that. I had to bring the events about which I had written forward to encompass architecture that had evolved from the ideas I had already identified, and I had to bring those ideas back to confirm roots in a longer history of the artistic avant-garde. What I had previously identified as a Deconstructivist movement was part of a longer history within which it could be situated and better understood. I had to three-dimensionalize the text.

What do you mean when you say that there’s been a fundamental shift in our culture, and that architecture needs to reflect that?

From the 19th century on, the very concept of space changed: after the topological mathematicians (Gauss, Poincaré) and, of course, Einstein, it was no longer Euclidean or Cartesian. Nietzsche declared the death of God, and mankind lost its organizing magnet. After the First World War, there have been paradigm-shifting events in culture—deeply disruptive changes in science, arts, religion, and (of course) history, including two world wars, Hiroshima, and the Holocaust. Abrupt upheavals eroding history, once perceived as a gradually evolving whole, of course had to affect architecture, which is, after all, a social construct. In 1931, the U.S. came off the gold standard. Late in the 20th century, the computer and 3-D modeling introduced differential calculus into design, confirming the notions that space, like history and life itself, is a matter of flux, change, and difference.

The contributions of Claude Parent and Robert Venturi?

Venturi identified problems with Modern architecture: that it was simple to the point of being simplistic. Function defined Modernism’s raison d’être in an ideology that streamlined anything non-conformist from the design equation. Venturi understood architecture in terms of words, symbols, and meanings, taking it out of the realm of experiences into a world of signs on billboards. He flattened architecture, de-spatializing it. Parent, who espoused the “function of the oblique,” basically returned architecture to the realm of space and experience, to architecture that was sensed and known through the body. A person felt the tug of gravity ascending an oblique plane, and its push, descending.

Of Gehry?

Gehry cracked open the profession by escaping architecture into art. He abandoned the parallel rule and the other instruments that regulated the drafting table. He sculpted buildings in models, testing designs, challenging the notion that the plan was the generator, and that the right angle was, as Corb had said, divine. He exchanged Apollonian architecture for a freer, more wild Dionysian architecture that was no longer static but outside stasis—ecstatic. His intuitive architecture tapped into deeper roots of architecture’s subconscious.

Of Hadid?

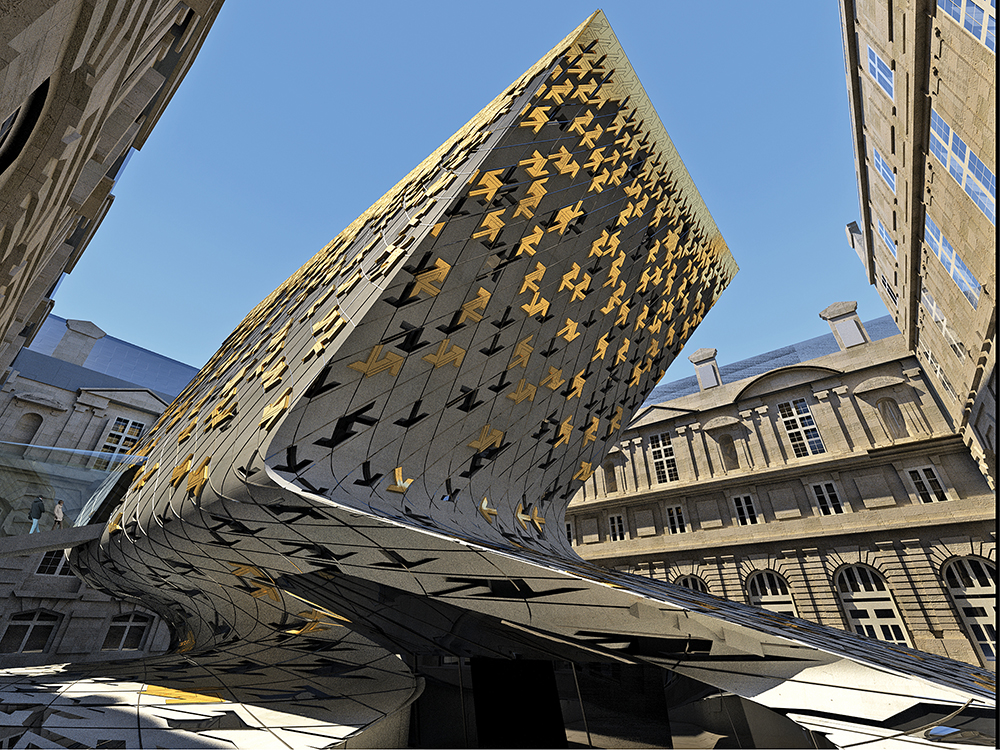

Hadid opened the history books again to develop ideas that history had aborted. She found Russian Suprematism especially promising, and realized its strange and four-dimensional concepts of space in buildings that Suprematists had never succeeded in building. Devising her own methodologies, she explored painting as a way of finding a new kind of warped Einsteinian space, which led to the fluidity of the plan, and eventually, especially with the computer, to liquid architecture. Her vision, already radical before the computer, intersected with the new technology to make major leaps of the imagination into new architectural territory, even at very large scale. In addition to her towering talent and impeccable eye, she had great organizational abilities that powered her office to its extraordinary international successes.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2414]