A three-day design charrette in Raleigh, N.C. will commence tonight, as five leading New York architects, planners and landscape architects join about 70 of their North Carolina counterparts at the Contemporary Art Museum in the city’s burgeoning warehouse district. Each of the New York designers – Michael Samuelian from The Trust for Governor’s Island, Marianne Kwok and Claudia Cusamano from KPF, Thomas Woltz from Nelson Byrd Woltz and Andre Kikoski of Andre Kikoski Architect – will be giving 20-minute, TED-like talks this evening. Tomorrow, all will break up into teams to rethink an 81.2 acre site in the center of downtown and on Sunday afternoon, they’ll present their findings to the public. Today, A+A is reprinting this writer’s May 4 “Skyline” column about “Connections 81.2” from The News & Observer in Raleigh:

As Raleigh, N.C. begins to think seriously about what it is and where it’s heading, it’s a good time to shift the focus to an area that should be central to that vision.

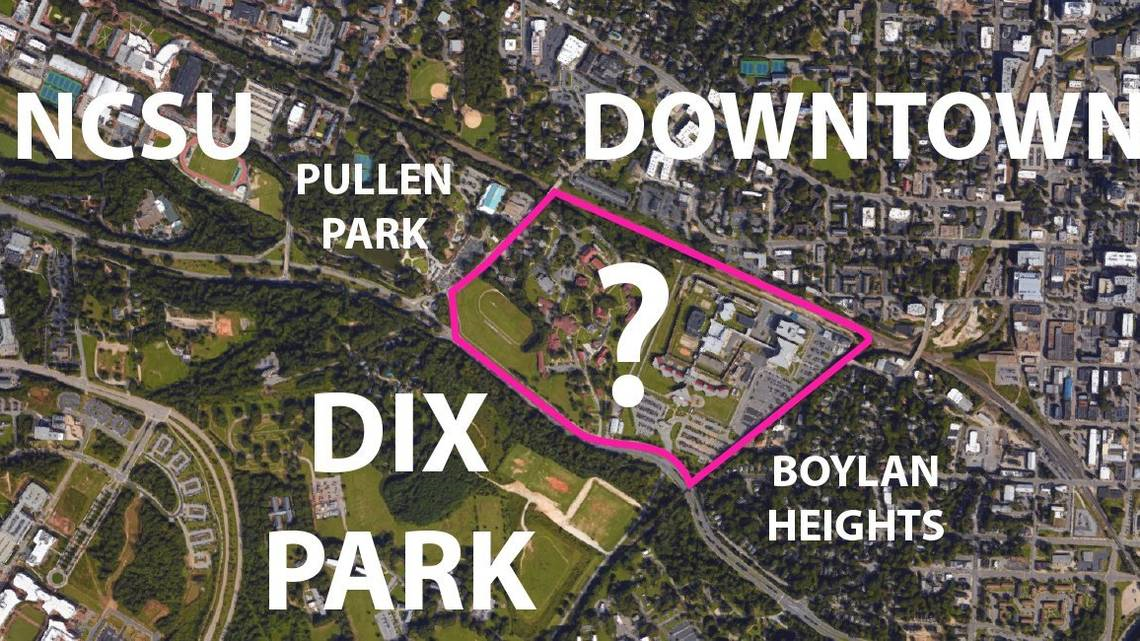

That area is 81.2 acres now occupied by Central Prison and Governor Morehead School for the Blind — off Western Boulevard — that’s considered a connective tissue between downtown and Dix Park.

And for three days this month, local and nationally known architects will lead a rare conversation about design excellence for downtown Raleigh, bringing a fresh perspective as they focus on new solutions and hypothetical ideas for the large property.

“It serves as a hinge point between so many things — Dix Park, N.C. State’s Centennial Campus, Pullen Park, historic Boylan Heights to the east and the Kirby-Bilyeu neighborhood,” says Erin Sterling Lewis, architect and organizer of the event.

Five leading designers, planners and landscape architects from New York City will join North Carolina architects from May 18-20 for a weekend of events. Organizers are counting heavily on public participation at some of the events.

“There’s a need for downtown and Dix Park and N.C. State to really be seen not separately as they are today, but joined in an intense urban community,” says Clearscapes’ Steve Schuster, a former Raleigh planning commission chair.

The designers will break out into eight teams May 19 in what’s called a charrette – a 19th-century French term that’s shorthand for an intense, day-long effort. This charrette, called “Connections 81.2,” is aptly named.

The public is invited to bring their ideas to two of the events. Friday evening, May 18, there will be a series of TED-like talks from the New York visitors. On Sunday, May 20, there will be presentations of the designers’ solutions from the charrette.

The weekend is organized by AIA Triangle and this website, Architects + Artisans.

“It sounds like an enormous opportunity,” says Michael Samuelian, urban planner and president/CEO of The Trust for Governors Island in New York. “A big site is something you rarely get — usually it’s block-by-block, but we’re designing an entire city here.”

Samuelian is one of the five New York designers who will participate in the charrette. He is responsible for planning New York’s Hudson Yards — first for the City of New York and then for The Related Companies. It’s the largest mixed-use development in Manhattan since Rockefeller Center, and the largest private development project in the history of the country. Five of its towers are under construction — from 1,000 to 1,300 feet tall — all built atop a working rail yard 200 feet below grade.

Others include Thomas Woltz, a North Carolina native whose Lenoir County roots go back to the early 18th century. He is a landscape architect designing a 5-acre park at Hudson Yards.

Two designers from Kohn Pedersen Fox will participate: Marianne Kwok, design director for 10 and 30 Hudson Yards, and Claudia Cusamano, KPF Director and project manager at 30 Hudson Yards. Also on hand will be Andre Kikoski, interior architect for One Hudson Yards, Chelsea’s newest rental building adjacent to the development.

A massive site

Raleigh’s 81.2-acre site is roughly three times the size of Hudson Yards’ 26 acres. The thinking among local planners is that Central Prison will eventually move from the site, opening up possible opportunities for mixed-use development.

“That’s one of several hundred-million-dollar questions,” says Schuster. “Do we invest significant dollars to put it somewhere else? Or does part of it stay? That’s one of a series of long-term issues to decide.”

Design teams will be required to include a re-imagined Governor Morehead School for the Blind into the hypothetical development, including programatic elements of their campus currently located off site, Lewis said.

Local architects anticipate a fresh set of New York eyes looking at downtown, as well as a different blend of experience and expertise — and no small amount of buzz.

“They bring, under certain circumstances, a little star power that builds momentum – or at least publicity, and that’s not to be undervalued,” says Mark Hoversten, dean of N.C. State’s College of Design.

There’s inspiration too, as the local community begins to ponder the difficulties of developing the site.

“One of the ideas of bringing them down here, with Hudson Yards in particular, is how absolutely impossible it seemed to ever develop that site and at the same time make it beautiful,” Lewis says. “We want our New York friends to inspire us and encourage us to aim high.”

North Carolina architects will bring knowledge, commitment and compassion to the table – as well as substantial design talent. Plus, there’s enthusiasm borne out of a commitment to their home town.

“They’ve got an awareness of North Carolina as a place you can live well in, with its climate, people and aspirations,” says architect Frank Harmon.

Public input

Question and answer sessions will be held Friday and Sunday. And questions already abound — like the potential for market-rate and affordable housing, offices, restaurants, retail and open space — all directly across Western Boulevard from Dix Park.

“This is an ideas workshop,” Harmon said. “People from this area have thought about this site, and the city is thinking about what will happen with this piece of land. People want to live here. They come here by the hundreds every week, and we can’t keep building roads and houses on quarter-acre lots – and we need a healthy city.”

“Connections 81.2” promises the beginning of a conversation about that city’s design. It’s not planned as a one-time event, either. Rather, it’s viewed as the first of many discussions about what Raleigh’s physical environment will look like in 10, 20 or 50 years. It’s significant in its status as an initial step for North Carolina’s design community.

“If we as architects and planners don’t think about the city’s design, it will be done by capitalism, and capitalism doesn’t always make a good city,” says Harmon. “This way, we take responsibility for it and not do what’s always been done in Atlanta, Charlotte and Richmond. What we need is a living model – one that’s about how we live together – not a profit model.”

To be sure, the development community will be engaged actively in this charrette’s discussions, because they’re the risk-takers for any design project’s construction. The ideal outcome though, will be a marriage of public wants and needs, developers’ return on investment and excellence in design from the architecture community.

“The genius of this charrette is that it will be met with compassion and care from that community,” says Kikoski, the architect from New York. “Great conversations and ideas can happen from what residents and developers feel, think, need and aspire to.

“We’re all humanists – nobody goes into architecture saying: ‘I just want to make pretty things – leave me alone.’ Everybody in this profession cares about people.”

Great design for downtown Raleigh may be challenging, but it’s not impossible. Consider Hudson Yards. That project started with four planners in 2008. Now there are 300 on staff, working daily on a new skyline for New York City.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=1915]