Fresh out of Harvard’s GSD in the late 1980s, Naomi Pollock suddenly found herself face-to-face with a new academic advisor at Tokyo University’s graduate school of architecture.

She was there because her husband had been offered an opportunity in Japan – which gave her the opportunity to survey the local design landscape.

Her advisor asked what she wanted to study about Japanese architecture, and her response was succinct:

“Why Japanese buildings look so weird,” she answered.

She didn’t understand, she says, the strangely shaped roofs that didn’t relate to each other, and the scale of a city that seemed so variable.

Her advisor’s response: “If you want to understand the current buildings, you have to understand the traditional ones.”

Going back to Japan’s roots made sense. She looked to its rural farmhouses and their thick, thatched roofs. “I was interested in their use of materials,” she says.

But she still had an interest in what was going on with contemporary buildings. Luckily, she found that Japanese architects had a practice of holding open houses before turning a building over to a client. “They invite everyone they know, including family, architects and students,” she says. “I got invited to a lot and went to as many as I could.”

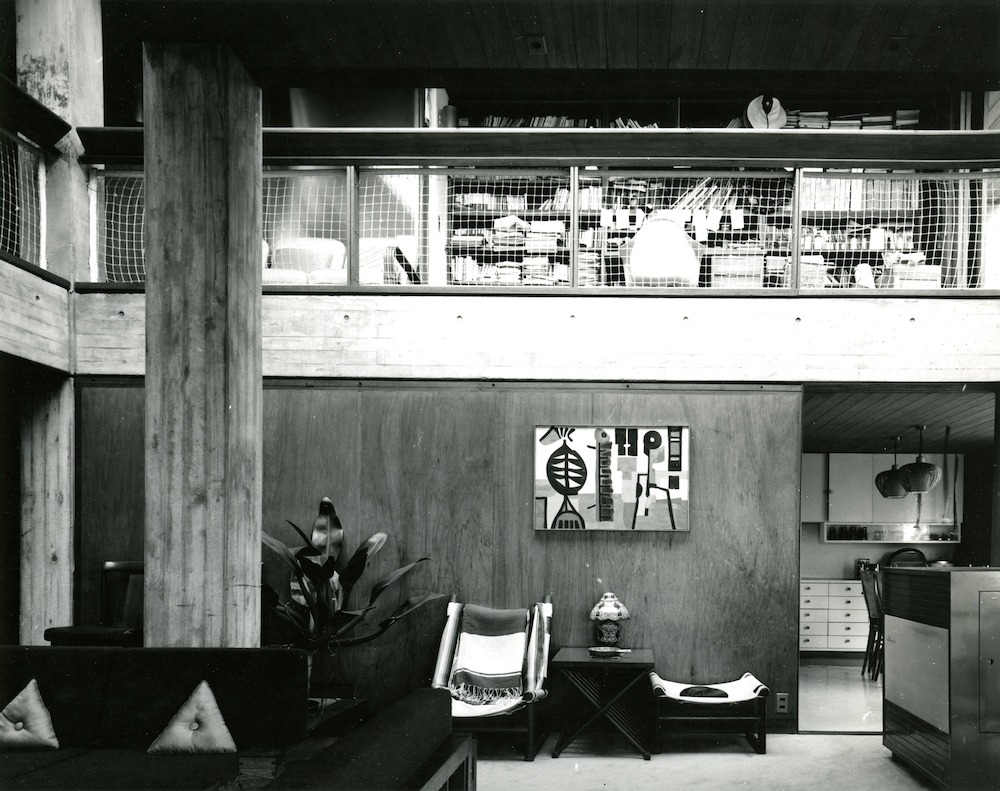

By 1999, she was writing a catalog for a Chicago exhibition. Her first standalone book was in 2003, called “The Modern Japanese House,” offered about 25 houses compiled from her work as a graduate student.

She found that her calling lay with writing, and not design at all. Eight more books would follow. The newest is from Thames & Hudson, called “Japanese Houses Since 1945,” and covers the waterfront of Japanese single family homes. “I thought that if I could take 100 of the most important houses built since 1945 to the present, then what would my lineup be?” she says.

The book’s divided by decades, each featuring a selection of houses that were impactful in their time. “I wasn’t looking for the zebras, but the thoroughbreds with a lasting impact,” she says.

Scale and proportion are themes throughout. “In the West we think bigger is categorically better,” she says. “In Japan, quantity is not equated with quality.

A Japanese single-family home has no backyard. There may be a lone flower in a pot out front, where it’s admired as much for its singular beauty as an entire field’s.

No one, she notes. complains about size, because they’re more interested in the quality of their spaces. “They want to be able to sense the presence of other family members – the sense that ‘My mother’s home,’ or ‘My child is home,” she says. “Audible cues are very important. But doors? Not so much.”

Materials are important too. Concrete is used frequently, as are paper, plastic and metal. “Japan has always used a wide range,” she says. “That thinking about what a building could be made of, the possibilities, has always been very broad.”

And her advisor was right. Understanding the traditional is a key to understanding the contemporary. Even today, the Japanese will come home, take off their street shoes and put on their indoor slippers. “The history they come from is still alive and well,” she says.

In her new book Pollock is defining a modernism that’s been evolving for 80 years.

But alongside that evolution, the intrinsic Japanese culture endures.

For more, go here.