As anthropologists ponder the meaning of Charlie Sheen’s recent chair-smashing fit at The Plaza, and a course at the University of South Carolina meanders off into the sociology of fame – looking closely at Lady Gaga, nee Stefani Joanne Angelina Germanotta – others elsewhere are delving into a far more intriguing enigma:

Thomas Jefferson’s use of symbolism in his entablatures at Monticello, Poplar Forest, and the University of Virginia.

“What’s he saying with these? I don’t think he ever comments on why he used one versus another,” says Travis McDonald, director of architectural restoration at Poplar Forest, Jefferson’s Palladian retreat near Lynchburg, Va. about the variety of figures there.

“Why mix them up? I’m sort of at a loss,” says Bill Beiswanger, director of restoration at Monticello. “They’re beautiful forms. But always with Jefferson, it’s not what we know now, but what he knew then.”

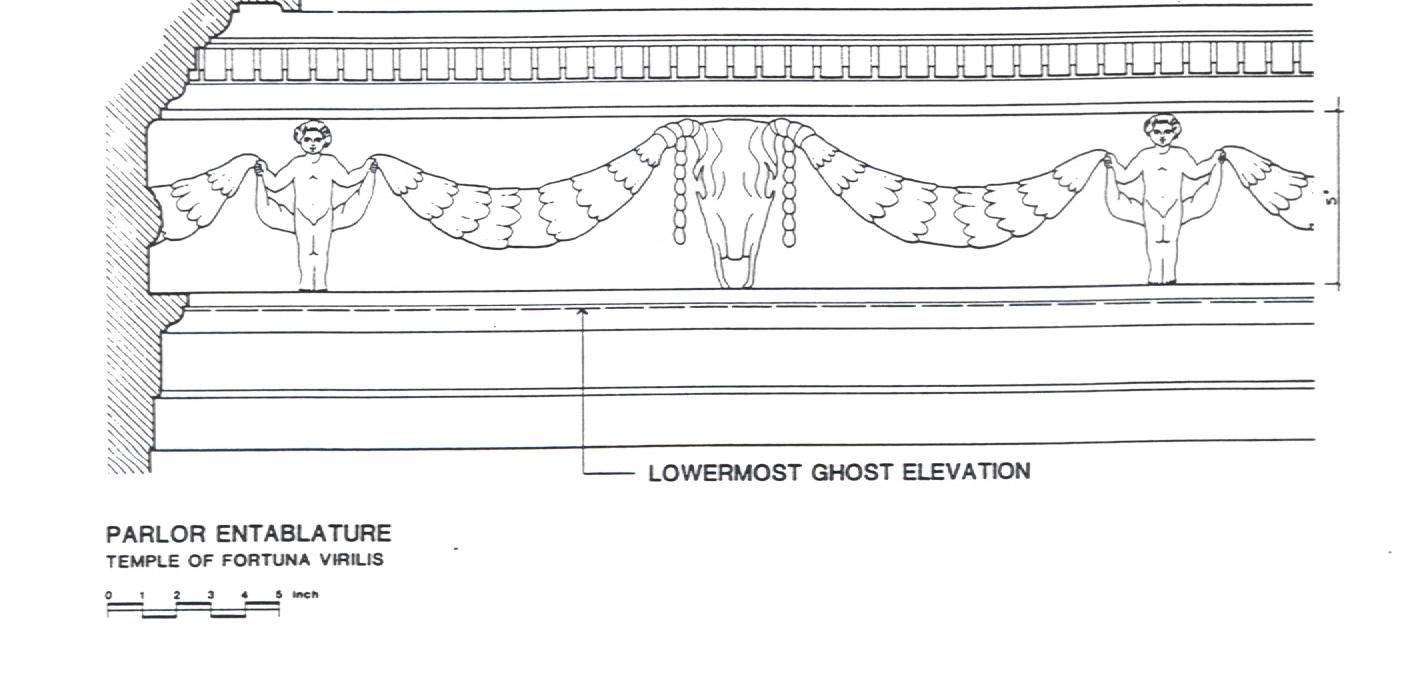

Among the symbols is Apollo, the Roman god of light associated with the sun, and the patriarch of poetry, music and creative arts in general. Then there’s Fortuna Virilis, the powerful Roman goddess of manly luck. She stood for the tandems of riches and poverty, pleasure and misfortune, blessings and pain. She was also the protector of cities, and could deliver fertility.

And what of the tiny Putto (In Latin, a putus is a little man) or Amoretto? “They’re form merged with the genii of Roman religion, guardian spirits that protected a man’s soul during his life, and finally conducted it to heaven,” McDonald says.

And finally, there’s the skull of a bull or ox, which the Romans associated with sacrifice, self-denial and chastity, but which also stood for agriculture, foundation-laying, and patience personified.

Jefferson was deliberately mixing and matching symbols of the ancient architectural orders, though not in his public buildings like those at U.Va. But at his private residences, he didn’t hesitate.

That’s particularly true at his most mature masterpiece, Poplar Forest, which he designed in the shape of an octagon – a form that itself is the symbolic, regenerative link between square and circle, earth and sky, terrestrial and eternal.

“You are right…those of the Baths of Diocletian are all human faces…” he wrote to sculptor William Coffee in New York, who created the icons for his entablatures. “But in my middle room at Poplar Forest I mean to mix the faces and ox-skulls, a fancy I can indulge in my own case, altho in a public work I feel bound to follow authority strictly.”

“He felt obligated to explain why he would deviate from the order to Coffee – and even to himself,” Beiswanger says.

But there’s no evidence that he used them to speak to the ages with them.

“I find it hard to say that Jefferson is talking in true symbolism, and using architecture as a story,” he says. “He was looking to the beauty of the form and the ornament of antiquity. We have yet to find him referencing them as symbolism.”

Still, they’re freighted with meaning that’s all too rare in our public discourse up here in 2010.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=240]