An array of wall paintings, sculptures, mosaics, cameo glass and silver vessels created in Roman Italy between 100 BC and AD 250 will soon be on display at the San Antonio Museum of Art in Texas.

Among the paintings are frescoes from Pompeii – preserved by the ash and debris from the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D. “The mural paintings came from masonry buildings and plaster walls,” says Jessica Powers, SAMA’s curator of art of the ancient Mediterranean World. “For the paintings to survive, the walls had to survive.”

Tomb paintings started out underground, so they were preserved there, then removed as early as the 17th century for the Italian Royal collection of the City of Naples.

Powers organized the exhibition, plunging into SANA’s collection of more than 3,000 ancient Greek and Roman artifacts. She also reached out to curators in London, Munich, and Paris to add to his displays – with a number of items that have never set foot in the U.S.

“It was an idea that I developed, and came out of work that I have done over the years in Pompei and Rome,” she says. “I’m increasingly drawn to landscape paintings with trees and buildings, and shrines people are coming to.”

The 66 works are not large, but they are intricate, with a great deal of inventiveness in them. “The paintings are from the first century B.C. and the first century A.D.,” she says. “They are two thousand years old, and all Italian.”

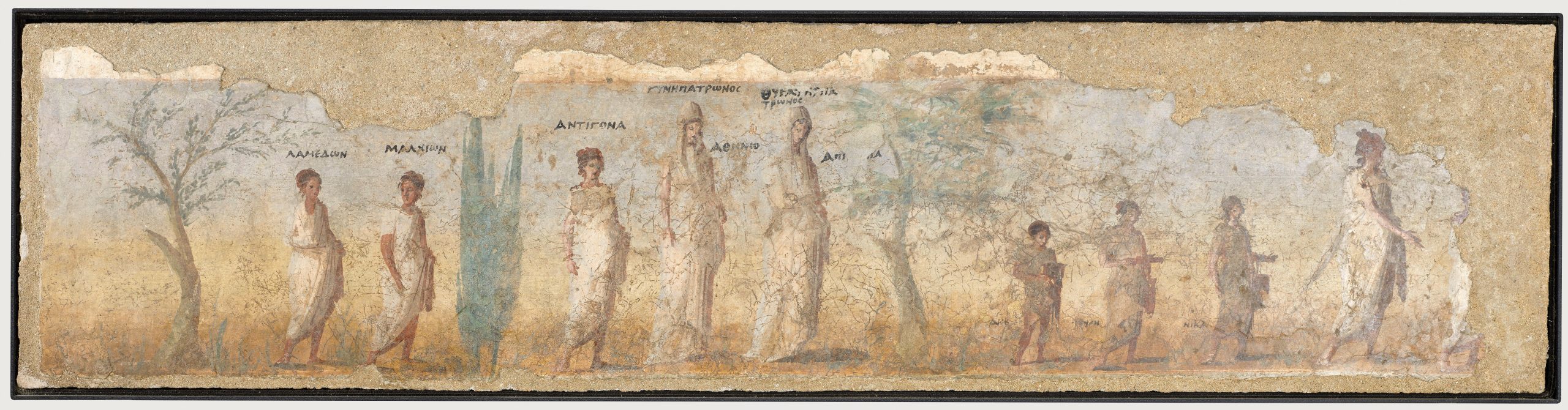

Much of the exhibition examines the development of landscape architecture in Roman art and how Romans viewed their relationship to it, as wealth poured into the empire. Part of that was a sense of nostalgia to preserve buildings, shrines, and ancient trees. “It looks at spaces like mountains, springs. and the forest, with humans encountering gods in nature,” she says. “A lot are impressionistic in style, where a squiggle of white or red becomes a person in light or shadow.”

The exhibition re-examines the imperialist nature of the empire too, with the idea of colonies maintaining their identity while adapting to the Roman concept of conquest. It’s about how the Romans celebrated these areas – while reiterating their control.

“The Roman bureaucracy was never as large as we think of today – I perceive it as spotty in some areas and interested in others, with the Romans not able to manage and control things the way we are accustomed to today,” she says. “The empire had hugely different languages and cultures, and for the most part they continued under Roman rule.”

At home, the Romans were very much aware in the first century B.C. that their civilization was located on a peninsula with limited land of maximum value. There was land confiscation by the government, and much promised to war veterans. So land was a valuable, contested asset.

At the same time, the empire was becoming extensively wealthy with lavish villas built and landowners thinking about how the enormous structures could be sited for maximum views of the water.

“They would build on a hilltop so it would fit within the landscape,” she says. “And it was a productive landscape as well, so they incorporated gardens into the house itself with courtyards and lightwells to bring nature in.”

All of this is demonstrated in the SANA exhibition, along with mythmaking that accompanies life in the early Roman landscape. “It’s quite interesting – you see painters setting the stories out in the wilderness,” she says. “In the middle of the first century B.C. and later, there was mythological painting and landscape and humans encountering dangerous situations with monsters and gods who might eat or attack them.”

That includes depictions from the late first century B.C. into the early first century A.D., where Actaeon was hunting in the mountains and witnessed the goddess Diana bathing. “It was a mistake and he was turned into a stag and his dogs attacked him,” she says. “We have three different ways of artists showing this story, and a sculpture of Diana with a deer.”

“Roman Landscapes: Visions of Nature and Myth from Rome and Pompeii” opens on Feb. 24 and runs through May 21. But it will not travel; if you want to witness it, hop on a plane, train, or automobile and head for Texas in the spring.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2509]