Today’s post is the second from a feature I wrote for The Assembly, a statewide magazine that publishes deep reporting on power and place in North Carolina. It’s about a small town’s resilience in the face of crisis – and the changing nature of hurricanes here today. After getting whomped by Hurricane Florence, tiny Pollocksville used grit, grants and gumption to recover – and created a model for responding to rising water. A+A is pleased to publish it :

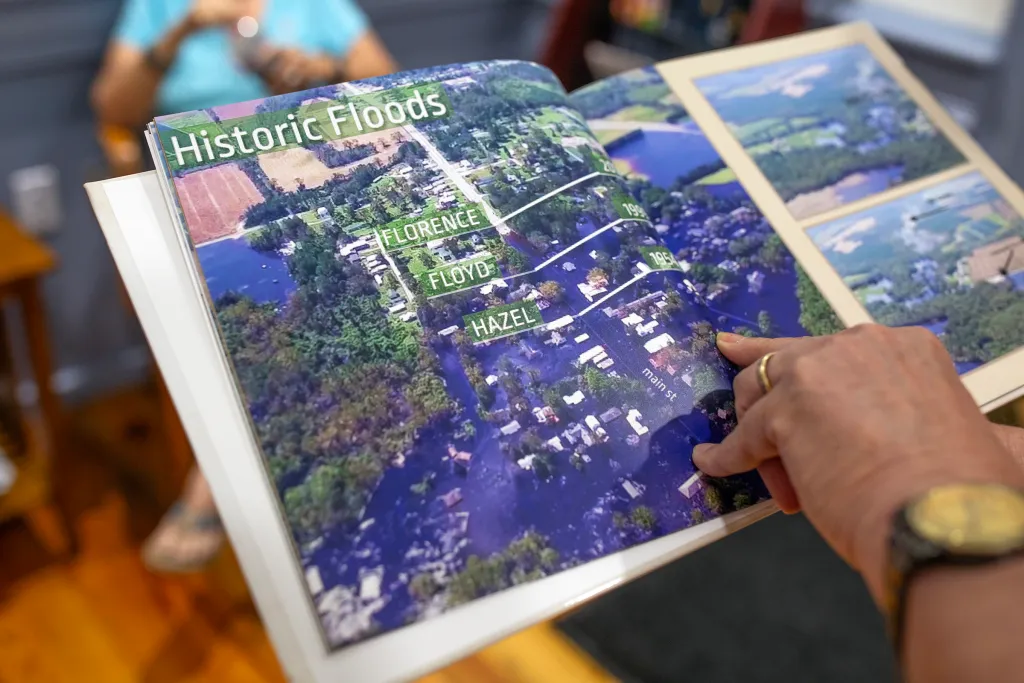

Hurricanes are moving slower across North Carolina than they once did, according to the North Carolina Sea Grant program, a research and education group affiliated with N.C. State. Sluggish tropical storms increase the likelihood of extreme rainfall and raise the risk of rivers flooding.

The amount of precipitation that falls during heavy storms has increased 27 percent over the last 60 years in the southeastern United States, and that trend is expected to continue in a warming climate. Higher intensity storms are projected to increase inland flooding by up to 40 percent by 2050 in North Carolina.

The lessons learned from Pollocksville’s continuing recovery can be applied to other communities across the state, said Fox, the lab’s director.

It’s important to find trusted partners, because small towns can’t go it alone.

Also, small recovery projects—and lots of them—add up to big change. One priority is to recognize what’s special about a community, and use that when thinking about adapting to the new climate reality.

“Why a place matters—its history, culture, riverfront or historic structures—can be used as a springboard to recovery, as opposed to giving it all up,” Fox said.

‘A Big Success Story’

Slowly but surely, structures in Pollocksville are being raised off the ground. Private funding elevated the Barrus House, built circa 1825, to 4 feet on brick piers. It’s architecturally significant, with a two-tiered front porch enclosed on one end and a front bay containing exterior stairs, a style common in Charleston, S.C., but not often found in eastern North Carolina.

In a floodplain about a block south of the river on what the mayor calls “Disaster Street” (actually Barrus Street), one home has been raised high on cinderblock walls. But five others nearby, all rental properties, will probably be bought by the state.

Should the owner accept, the houses will be demolished, the town will own the property and leave it undeveloped. They’ll replace the houses with publicly accessible park space, including bioretention areas—more depressed spaces where water can collect. “When a hurricane comes through, they’ll be underwater and then dry out,” said Fox, the NCSU lab director.

Last year, the lab won an award from the American Society of Landscape Architects for its work in Pollocksville.

“It’s a big success story,” Fox said. “Given how small a town it is shows what can be done.”

The work in Pollocksville isn’t done. Bids opened on July 13 for a Main Street enhancement project adding new sidewalks, plantings, and bioretention areas. The town has a $1 million grant from FEMA to elevate six downtown buildings. The hope is that the revitalized area will lure commerce back.

Entrepreneur Eddie Jenkins, a 60-year-old resident who lives in his great-grandmother’s house, had two businesses upended by Florence. He established his Grilling Buddies restaurant on Main Street eight years ago as the go-to place for breakfast and lunch. Years before that, he created a lawn service business, Mowing Buddies.

During the hurricane and subsequent flooding, his lawn service was inundated with 5 feet of water, and his restaurant with 6. But he was determined to get his restaurant back up and running.

A recent grant from the local electric company helped with a patio, tables, and umbrellas out front. Inside, another grant from The Sunday Supper in Raleigh, established in 2016 to help families and businesses affected by Hurricane Matthew, helped pay for a freezer and grill cover.

“We were blowed away,” Jenkins said. “It was somewhere around $25,000.”

When commissioner Barbee was growing up in Pollocksville in the 1950s and ‘60s, downtown was bustling with a bank, a grocery store, and furniture store. Most of the businesses were run by locals. When their children left town and didn’t return, all that commerce declined.

Immediately after Florence, about 50 people didn’t come back to town, reducing its population to 268. But the 275 people there now are determined to rebuild Pollocksville.

That includes Barbee. She may have lived in a FEMA trailer in her backyard for 18 months while restoring her home, but she stuck it out and found help from others. The Eight Days of Hope Church, a nationwide group with a rebuilding ministry in New Bern, sent volunteers to town and cleaned out her house.

Now that her home’s rebuilt, she’s got an optimistic eye on the future. She’d like to see a farmers market and a downtown coffee shop. Two years ago, a campground for the RV community opened on a manmade lake on the outskirts of town. “People come from all over—they’re full all the time,” she said.

And downtown, the once-popular Trent Restaurant, closed in the 2000s, has been bought. Barbee hopes to see it reopen and serve dinner to the out-of-town campers, its apartment above occupied.

“We have a bright future, but we’re still in recovery mode,” she said. “We’re small, but we’ve got heart—big hearts.”

For more, go here.