When JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon says that for every 100 employees, the bank will need seats for only 60 in future offices, he’s painting a different picture for the future of New York‘s commercial real estate market.

The bank’s is going to move forward with its new headquarters though, and Google, Facebook and Amazon plan to expand their presence too.

That’s because New York still symbolizes success, says Manhattan-based architect Carmi Bee, president of RKTB. “That’s the reason why years ago Walter Chrysler built the Chrysler Building, and Woolworth also – it’s the symbolic nature of the buildings,” he says. “New York’s a port of entry for all kinds of goods from Europe, it’s the center of arts and culture – and it’s a big center.”

Now it’s a big center with an abundance of empty office space. In 2020, office leasing volume in Manhattan declined by 51 percent from 2019, according to the New York CityBizList. And Bee, a 1970 graduate of the Princeton School of Architecture – whose firm has converted 10 to 12 office or light manufacturing buildings into residences – sees a similar trend for the future.

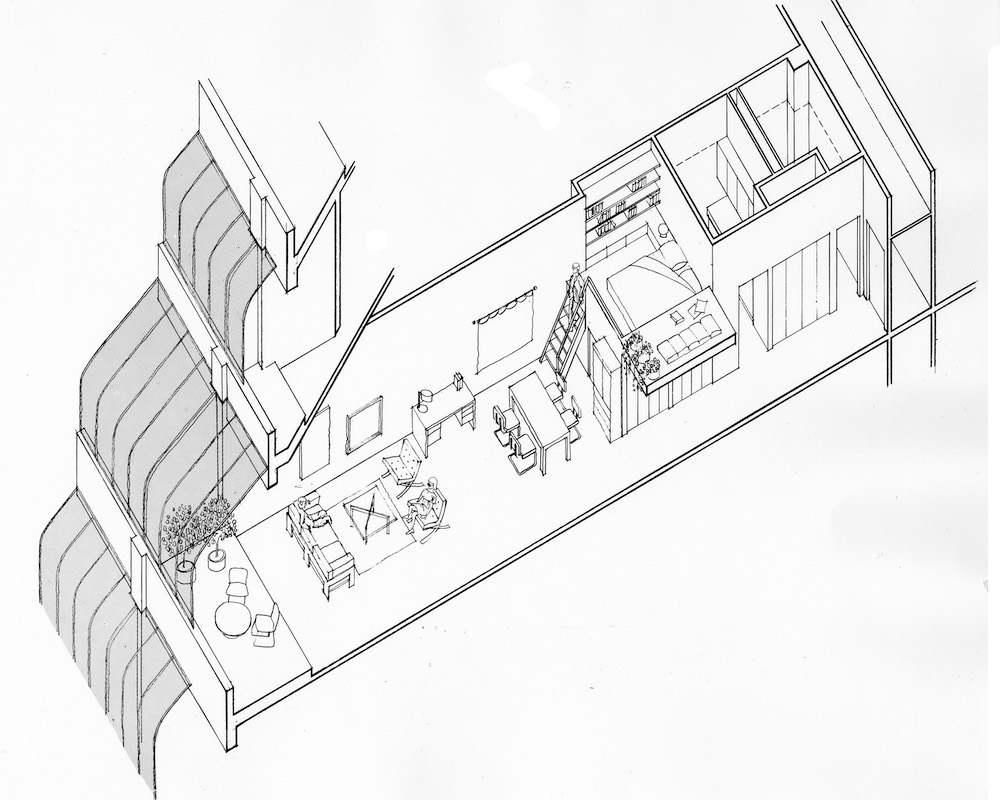

In 1978, RKTB renovated the 26-story Turtle Bay Towers, a 1928 structure badly damaged in a gas explosion. The resulting 341 luxury rental apartments were recognized with a 1979 AIA National Award. “That was a seminal piece of design – an office and manufacturing building turned into luxury residences,” he says. “It coincided with artists flocking to live and work in loft spaces.”

This time, though, affordable housing may drive a new transition.

“There’s all this incredible vacant space and such a need for affordable housing,” he says. “Sooner or later it’s going to happen, and people will have to get used to the idea of workforce people and lower income people living cheek by jowl with people of means.”

To convert offices to residences there’s the practical, required ratio of window size to depth, to allow light into an apartment. Educational facilities could be prime tenants for empty offices, with similar needs. “They’re perfect to move into office space, as long as you can have access to an exterior wall with windows,” he says.

With many buildings like Turtle Bay Towers already converted in areas like the Garment and Financial Districts, all eyes are turning now to the new glut of office space. And while developments like Hudson Yards are likely to attract large corporations seeking success symbols, affordable housing is likely to play a key role elsewhere. “If life comes back to New York as it seems to be doing now, it’ll be figured out,” he says. “You’ll have to differentiate between existing and new office space.”

And if existing office space is to be opened up to affordable housing, financial incentives will be needed. “New York is so much in need of affordable and special needs housing – it’s staggering and pathetic,” he says. “It’s really badly needed, because of the lack of governmental programs to allow people to have affordable rent.”

The economics of the recovery, he says, will precede political will. “You make the economy of these buildings work, or politically we’re in a bad place,” he says. “Political will is a result of financial stimulation.”

He predicts that out-of-town corporations will return to the city, attracted by a ready-to-work, youthful labor market. “Young people will continue to want to be here and sow their oats,” he says. “Big corporations like Google have established themselves in New York because of the pool of young people who are ambitious and into stuff like food, art, and other people.”

All in all, Bee’s an optimistic architect who sees big things for the future of his native city – even as a pandemic lingers.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2300]