Poplar Forest, completed in 1826 near Lynchburg, Va., is far less known than Monticello, partly by design — Jefferson didn’t want people following him there — and partly because it remained in private hands until 1984. But it was Jefferson’s most intimate space, where he spent much of his post-presidency time, and it’s recognized by preservationists as the first full-sized octagonal house in the United States.

“It fills in a large missing chapter — 14 years — of his retirement,” said Travis McDonald, director of architectural restoration at Poplar Forest. “It was his most perfect and idealistic work of architecture.”

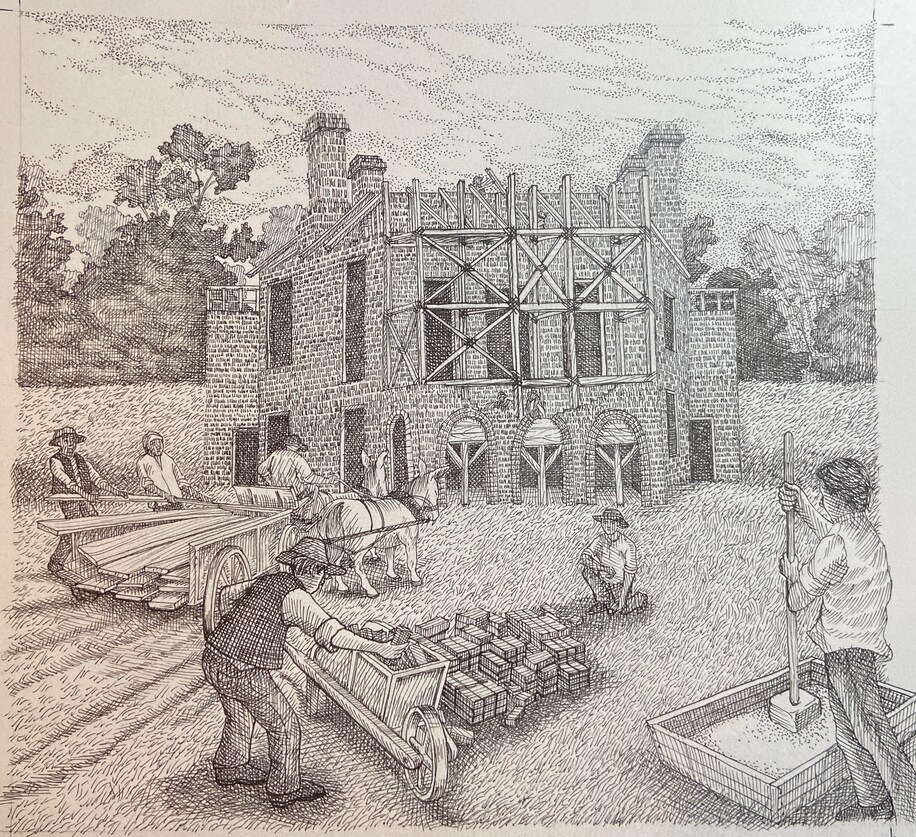

McDonald was hired in 1989 by the Corporation to Restore Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, a nonprofit formed in 1983 to acquire the much-degraded property and rebuild it to resemble its original state. It was meticulous work. Over three decades, McDonald, his staff, a pair of architectural consultants and an advisory panel restored the exterior and took the interior down to bare bones, then slowly realized Jefferson’s vision. To fill in the details, they looked to correspondence between Jefferson at Monticello and his workers at Poplar Forest 93 miles south — especially Hemings.

The former president, his family and his favorite joiner enjoyed a relationship that was unusually respectful for enslavers and the enslaved. Jefferson’s granddaughters taught Hemings to read and write. “He was very well regarded, and may have held Jefferson’s family in very high regard, even in the condition he was in — that condition being slavery,” said C.J. Frost, senior craftsman and supervisor of restoration work at Poplar Forest.

McDonald added, “The fact that Jefferson trusted John Hemings to work at Poplar Forest independently without supervision says a lot, since Jefferson always wanted to supervise even his best workers.”

In one letter from Monticello to Hemings at Poplar Forest in November 1819, Jefferson was specific about how their long-distance correspondence would work best:

“Write to me every Wednesday and put your letter the same day into the post office of New London or Lynchburg and it will be sure to be in Charlottesville on Saturday evening. In these letters state to me exactly what work is done, and what you will still have to do, and endeavor to guess at a day by which you think it may all be finished, that I may be ready to send for you by that day.”

For his part, Hemings worked sunrise to sunset on the 5,000-square-foot, four-bedroom retreat, as noted in his letter of November 1821:

“I am at worck in the morning by the time I can see and the very same at night. I have got the cornice nearly don. I am bout the tow last members dentil and quarter round. I should put an architrave on the skie light frame befour I take the Scaffold down.”

For more, go here.