On August 31, the Sarasota Art Museum will open ‘Art Deco: The Golden Age of Illustration,’ bringing together 100 rare and iconic posters from the interwar period, created by some of the most influential American and European graphic artists.

The exhibition showcases how both visual and material culture reflect the dynamic and progressive spirit of the interwar years—a turbulent, transformative era that found the perfect expression of its ideals and aspirations in Art Deco.

A+A recently interviewed Rangsook Yoon, senior curator at the Sarasota Art Museum via email about the exhibition. We’re pleased to run this interview in two parts – today and Tuesday:

Some background on the origins of Art Deco?

Art Deco was not a singular movement with a manifesto, but rather a convergence of diverse design ideas that took shape in the interwar years. The catalytic moment can be traced back to 1909, when the Ballets Russes’ arrived in Paris. The company’s spectacular performances accompanied by Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois’ bold, exotic costumes and Sergei Diaghilev’s experimental staging, electrified Parisian audiences. Their production and overall aesthetics challenging conventions epitomized their Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork) approach and sparked shifts across fashion, book illustration, interior design, architecture and the decorative arts. Another catalytic moment was the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter, which fueled a craze for Egyptian motifs and contributed to the broader sense of exoticism that permeated Art Deco design.

The style, referred at the time as style moderne or Jazz Moderne among other terms, was equally concerned with modernism, technological innovation and the rise of mass production and consumer culture. Its defining moment was the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) in Paris, which presented cutting-edge modernist design in national pavilions and showrooms representing twenty countries. This landmark event ultimately lent the style, or the movement, its name, Art Deco, establishing it as an international phenomenon. The term “Art Deco” itself, however, was not widely used until decades later, when British art historian Bevis Hillier popularized it in his seminal 1968 book, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.

Who were the original champions of the movement?

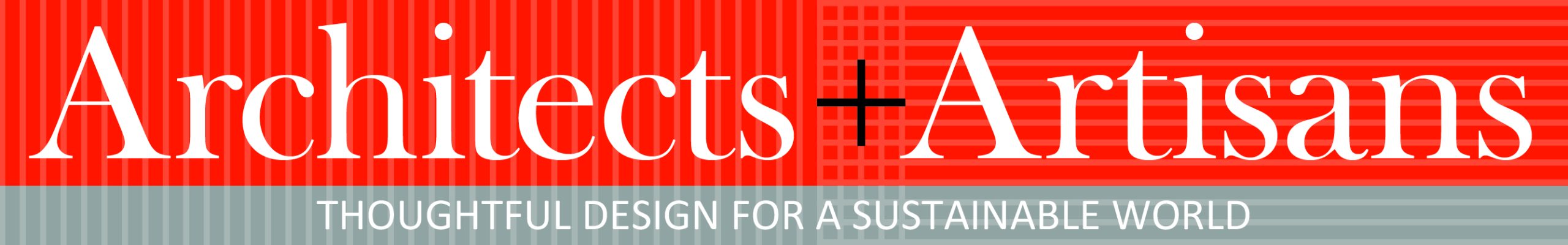

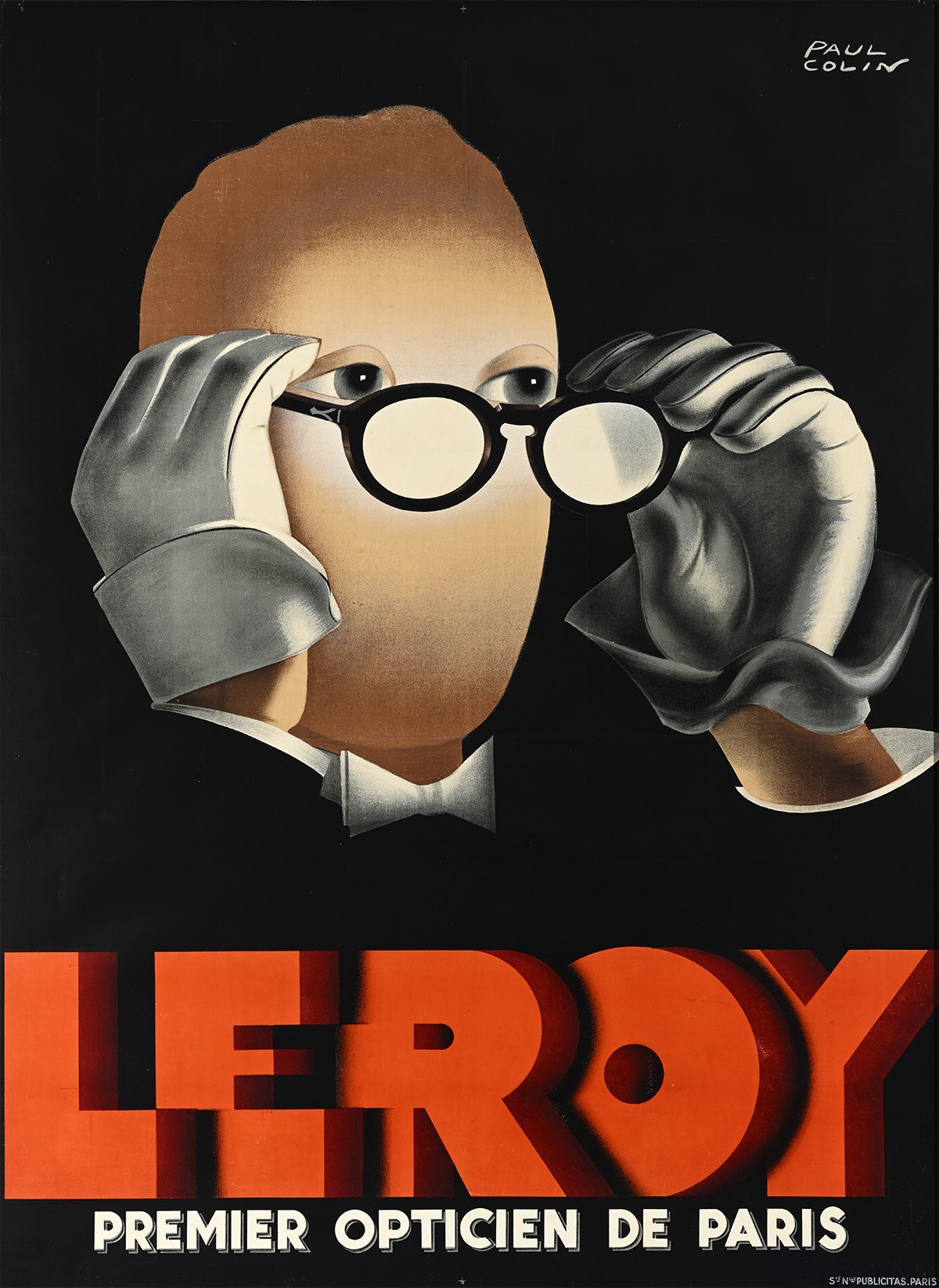

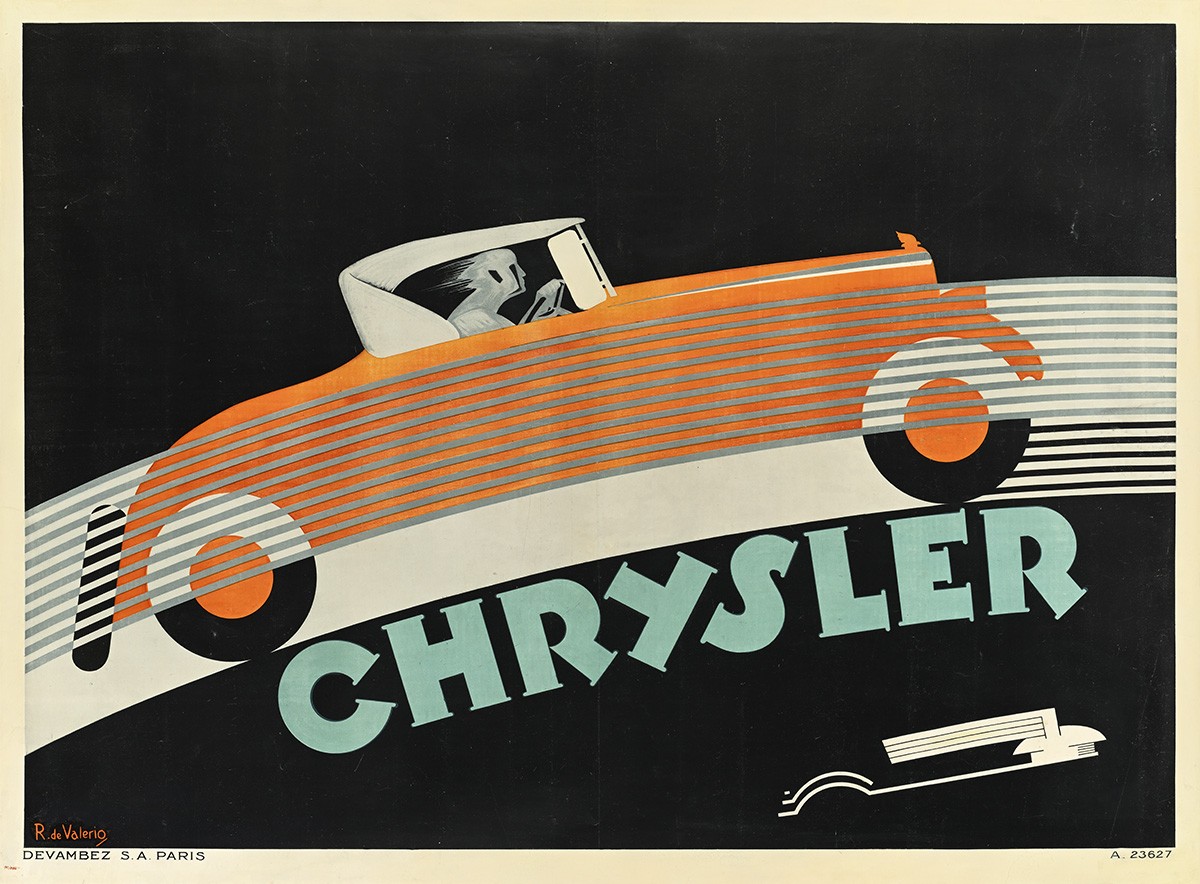

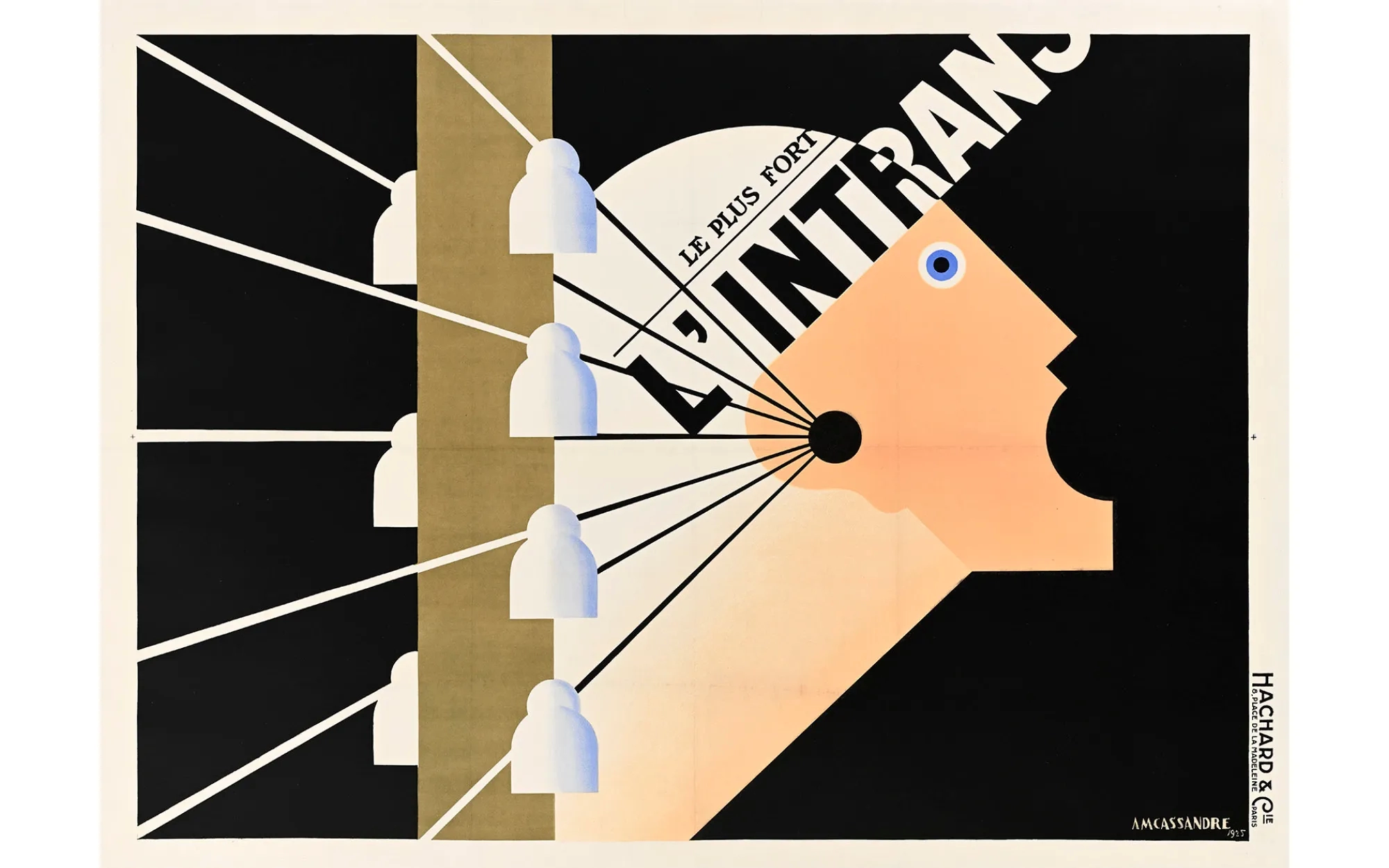

If we think about the figures who championed and defined Art Deco, they span many disciplines. To name only several “champion” artists, designers, and architects, in furniture design, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann was a leading figure. Among architects, Auguste Perret and Robert Mallet-Stevens in France, and William van Alen in the U.S. (best known for the Chrysler Building) helped establish and popularize the architectural language of Art Deco. In the realm of graphic design, A. M. Cassandre stands out for his stunning images, and Romain de Tirtoff, better known as Erté, for his elegant, highly stylized illustrations. In the fine arts, Tamara de Lempicka became emblematic with her sleek modern portraits. In fashion design, Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel translated Art Deco’s modern spirit, emphasizing functionality, streamlined elegance and a break from restrictive traditions.

At the Sarasota Art Museum, our exhibition highlights several champions directly. We are showcasing 19 posters by Cassandre, along with the only known poster designed by Mallet-Stevens, depicting La Pergola Casino at St. Jean-de-Luz, a building he himself designed.

What were they reacting against? What did they propose?

As a movement standing for modernity and progress, Art Deco emerged in reaction to several preceding design currents. It distanced itself from Art Nouveau, with its organic, flowing forms, sinuous and curvilinear lines, excessive ornamental elaboration of the Belle Époque. It also rejected various historicist revivals of the 19th century. While indebted to both Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts movement, Art Deco was against Arts & Crafts’ outmoded emphasis on handcraft and resistance to industrial production and luxury, which limited its appeal to a broader audience.

Instead, Art Deco championed a bold new aesthetic that reflected the spirit of the rapidly changing 20th century. By combining geometric abstraction with modern materials such as steel and glass, perceived as symbols of industrial age, and by drawing inspiration from both contemporary technology and distant cultures, artists and designers aspired to create a look that was forward-looking and celebratory of the modern progress, conveying optimism, sophistication and cosmopolitan flair as well as technological progress and the “machine aesthetic,” so visible at the 1925 Paris Exposition.

For more, go here.

On Tuesday: Art Deco’s reach beyond the decorative arts, its design intent and its links to modernism.