Peter Bafitis, managing principal at New York’s RKTB Architects, joined the firm in 1995.

But RKTB had been on the leading edge of adaptive reuse in the city since the 1970s, riding the wave of developer-driven, repurposed buildings in Manhattan, Brooklyn, the West Side and the West Village.

“It began with the dwindling number of warehouses and manufacturing businesses that left a lot of vacant buildings,” Bafitis says. “Developers saw opportunities, and we were pioneers in reuse for residences in them.”

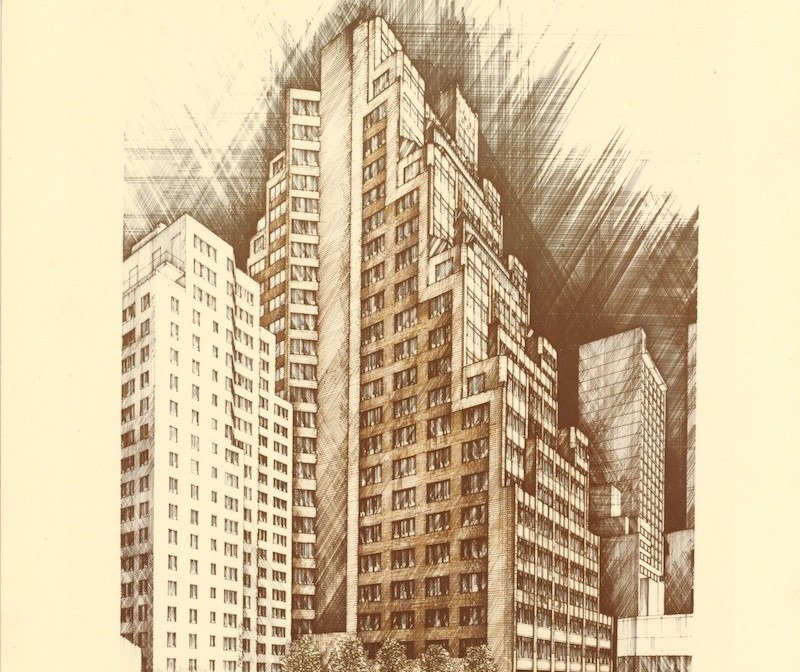

In the 1980s, they took on Turtle Bay Tower on the East Side of Manhattan, a former home to offices and light manufacturing. It had outlived its original functions, then suffered structural damage in a gas explosion. RKTB was hired to remake it into a landmark of adaptive reuse, with residences and lofts.

“It was when SoHo was gaining currency – and it was a new way of inhabiting a building,” he says. “That established our chops, and we’ve been doing it ever since.”

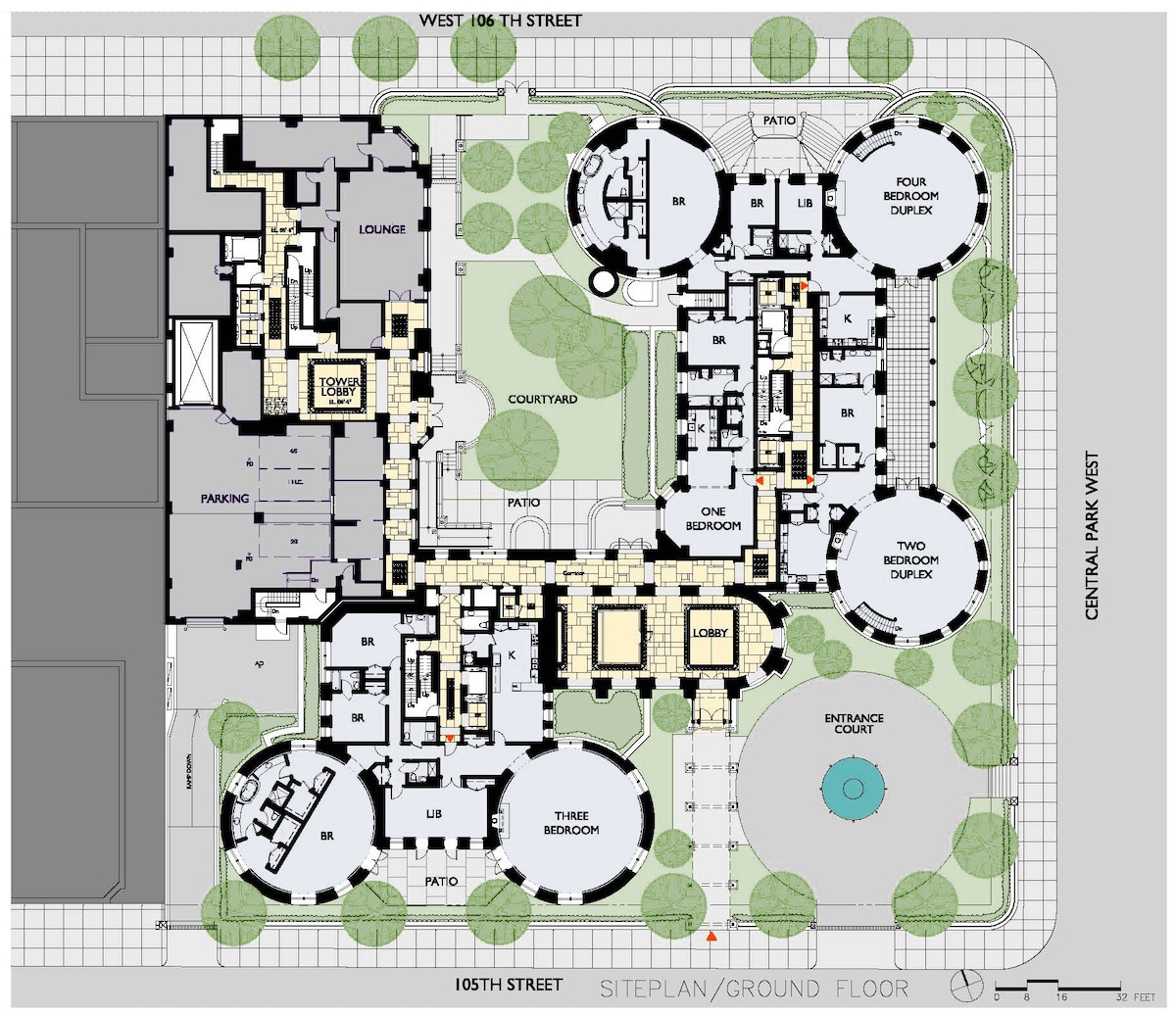

By the 1990s they were working through Lower Manhattan and a class of older, pre-World-War-II office buildings with small floor plates, seeking as much natural light as possible. “Those buildings lent themselves to adaptations,” he says. “They were good examples of buildings being converted because the original financial institutions were spreading out.”

Then came the newer, post-World-War-II buildings in Midtown with larger floorplates and more glass. The architects sliced off pieces of the structures to create atriums. “Still, it’s expensive to do that,” he says. “And it’s not economically viable if you have to do a total makeover.”

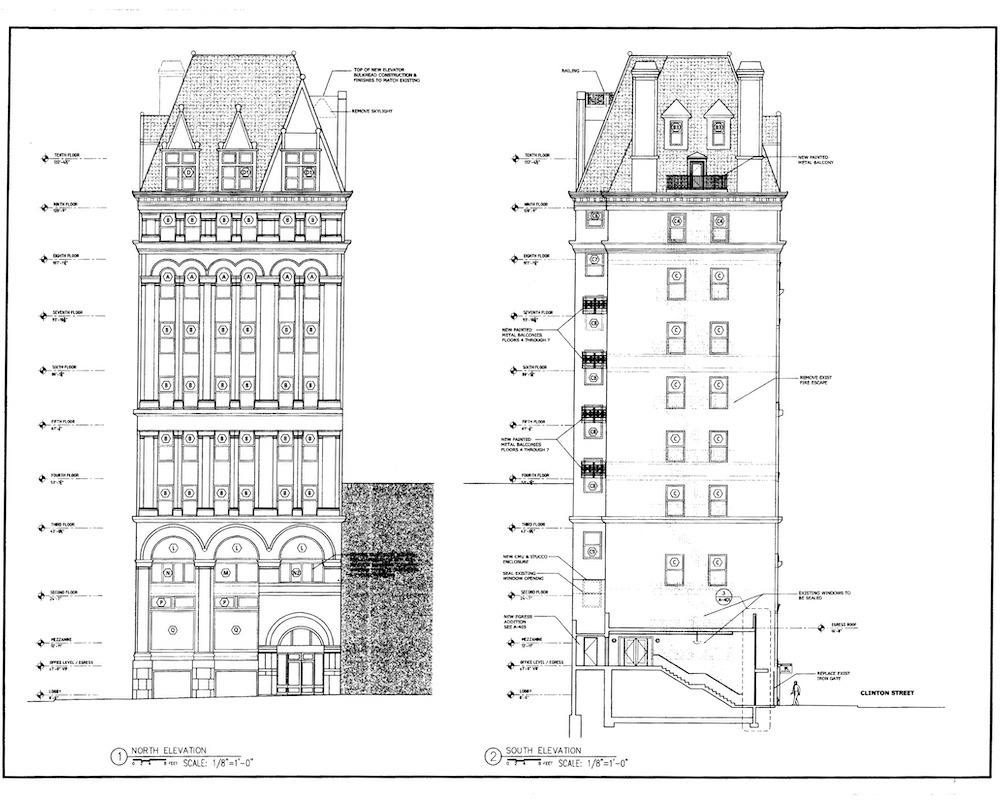

Today, the firm is eyeing the Class B and C buildings clustered predominately above 14th Street and below 59th. “It’s America’s largest office development district with millions of square feet – 20 million maybe,” he says. “It’s enormous.”

The aging building stock there is becoming obsolete, as businesses move to Class A space like Hudson Yards. Most of those structures have 1950s and 60s curtain walls, and need to be reskinned, with potential for new footprints. “And they need to be mixed use – you allocate residential on the periphery of the building,” he says. “There could even be urban farming for portions of it – there’s an opportunity to think creatively outside the box with them.”

After Mayor Adams’ recent push for adaptive reuse – specifically to turn empty commercial office space into affordable and market-rate housing – RKTB sees significant challenges, but also opportunities to alleviate the city’s housing crisis.

And they’ve got the chops to take them on.

For more, go here.