Like Charles Gwathmey, Michael Graves believed that a building should be more than its appearance.

“It should be an idea also,” says Ian Volner, author of a new critical biography of the modernist-turned-postmodernist-turned-healthcare architect.

“Michael’s life paralleled most design trends of the 20th century,” he says. “It was a little primer on one who passed through it, even with his illness, into design history.”

To be sure, his career was not without criticism and controversy. Graves was a lightning rod of sorts – someone who publicly attracted a non-architecture crowd to the profession, especially with his product designs for teakettles, mops, and brooms.

“Michael was the vector by which postmodern design entered the mainstream here,” he says. “He had a way of synthesizing it to the liking of the American public – and his work was far more palatable than Venturi’s.”

He was criticized by some for shifting gears from modernism to something new. The result was a reputation within the profession that began to crater in the 1980s. And his fame built on product design was derided as a money-making scheme – as a sellout for public attention.

But that wasn’t actually the case. “The contemporary architects who piled on for that were unfair,” he says. “The Arts and Crafts movement and the Bauhaus created a unified design environment, with no fear of designing a chair or a lamp, just as Michael did.”

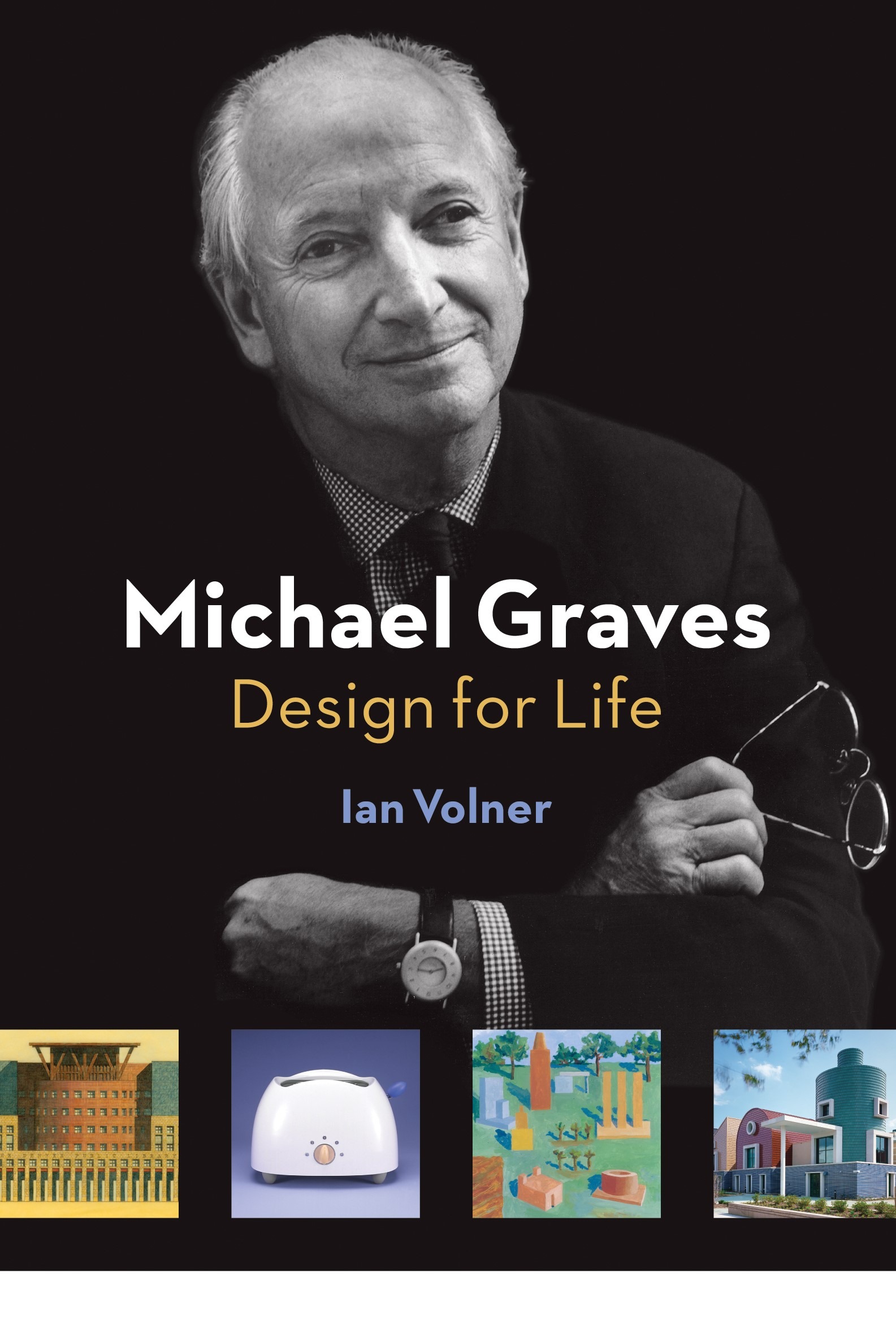

Volner got to know Graves as a public relations representative two years out of graduate school. He would travel from Manhattan to Princeton with him and his publicist, with considerable private access. That relationship would eventually turn into a collaboration on a memoir. When Graves died two years ago, the project was left in limbo – until Volner and Princeton Architectural Press decided to take the existing material and develop the biography.

Volner could have sought to rehabilitate Graves, or do a hatchet job on him. He chose neither. “It’s a qualified work of archeology,” he says. “There’s a core of Graves fans out there, and a lot of others are starting to reconsider him.”

For good reason. Anyone who’s slipped into the solemn, sanctuary-like lobby of the Humana Building in downtown Louisville can attest with certainty that they’ve basked in the work of a true modern master.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=1831]