In about two weeks, Oro Editions will release North Carolina architect Frank Harmon’s new book, ‘Native Places: Drawing as a Way to See.’ It’s a book of 64 drawings selected from the author’s website of the same name. Today, we reach back into the A+A archives for a 2011 post that Harmon wrote about one of the South’s most iconic plantations. Rich in layered observations, the post’s drawings are equally potent:

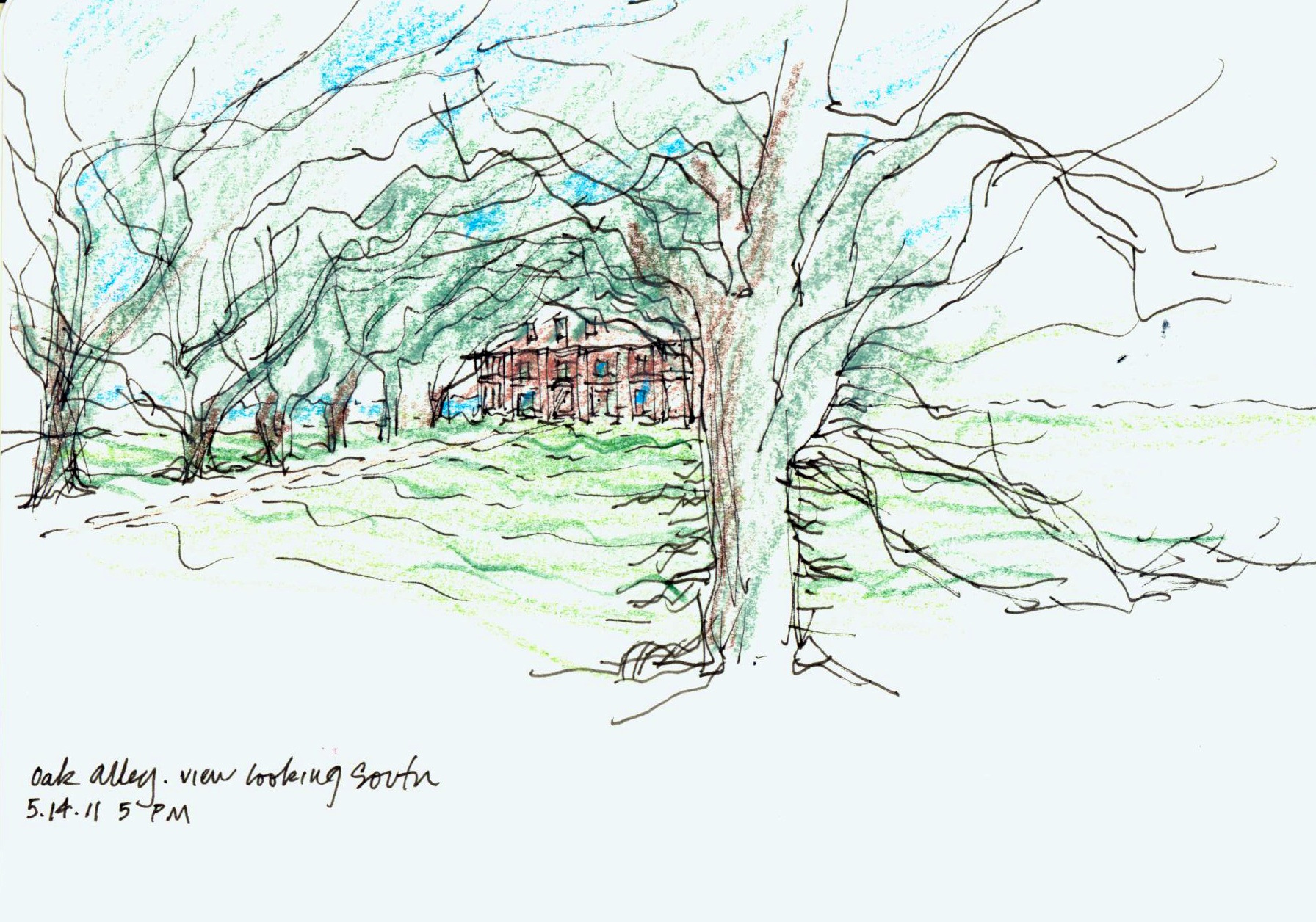

I went to see Oak Alley plantation in St James Parish, Louisiana, because of its shadows. An architect friend told me that the pattern of light and shade cast by its double row of 300-year-old live oak trees was unforgettable. The Mississippi River flows past one end of the alley of trees, which is about the length of two football fields. At the other end stands the plantation house, three stories high and wrapped in dusky pink columns that appear like trees of stone surmounted by foliage and dappled in shadow.

Few buildings are as evocative of the Deep South as the pillared mansion preceded by an alley of live oak trees. These ante bellum houses represent a gracious way of life, of languid afternoons on shaded porches, of mint juleps and magnolias, of a world of well-being.

Yet behind Oak Alley’s columns lie some practical strategies for coping with long, hot summers, such as porches that shade the mansion’s rooms, and the symmetry of spaces that allowed the family to inhabit rooms on the east side in summer to escape the afternoon sun, and to live in west-facing rooms in winter when the sun’s heat was welcome. Tall ceilings allowed hot air to circulate upward, and the legendary oak trees, planted 100 years before the mansion was built, shade the house and help steer the breeze through the house’s tall windows.

Today, Oak Alley’s plantation house is a flourishing events center where visitors arrive for business retreats, hold reunions, dine at sorority luncheons, and shop at crafts fairs. And then there are the weddings: Marriage ceremonies are as common at Oak Alley as magnolia blossoms, as are the preceding bridal showers, catered luncheons, engagement parties, bridal photographs and, later, anniversary dinners. Think Gone With the Wind that you can rent. Columns, trees and the river vista create a perfect wedding backdrop, suggesting a life of Southern charm, beauty and perfection.

It is easy to idealize a place as beautiful as Oak Alley, and the lives of the people who lived there. Perhaps our sense of a lost world is part of its fascination.

Yet the irony of Oak Alley is that life there was very different than we imagine.

Built in 1841 by a Creole planter for his bride, it suffered a series of misfortunes. First, the bride hated the remoteness of the house and refused to live there, preferring the social life of New Orleans. And of course, the entire enterprise was founded on human bondage.

Also, the man who built it died of pneumonia after living there only seven years. His wife died two years later. Indeed many of its inhabitants lived short lives as a result of malaria, cholera and yellow fever. In fact, one of the 20 rooms was a mourning room to shelter the deceased prior to burial.

After the Civil War, the children who inherited Oak Alley were forced to sell it at auction for a pittance. The house stayed empty for decades until it was restored in the 1920s to begin its present life as a wedding backdrop and tourist attraction — just in time for Margaret Mitchell’s epochal Southern novel “Gone With The Wind.”

One might say that Oak Alley has a far happier life today than the life that originally took place there – a life we have romanticized over time.

Twenty-eight columns surround the house just as there are 28 trees that form the alley. Trees and columns cast shadows that vary daily and seasonally, much like a sundial. There is something timeless about this uniquely American dream house and its enchanted grove of trees.

In London recently, another enchanted grove of trees adorned the great stone nave of Westminster Abbey for Kate Middleton’s and Prince William’s royal wedding. Elizabeth Sinclair, the wife of the recently disgraced Dominique Strauss Kahn, wrote of the royal wedding, “I can understand those who didn’t want to miss a crumb. As if, quite simply, we were children who, before going to sleep want a tale, a story with a princess and a dream, because real life catches up with you soon enough.”

Late on the May afternoon when I visited Oak Alley, one wedding was in progress while another was queuing up — pretty girls in gowns laughing, young men in formal wear chafing each other. Hopes for the future contrasted with a more troubling reality at the other end of the alley, where the levee held back the Mississippi River, now surging at a level higher than the roof of the plantation house. Perhaps its witness to slavery, plague, war, and flood makes the beauty of Oak Alley more poignant.

As evening fell and the wedding candles were lit, none of that seemed to matter. We were bathed in the shadow of romantic art.

– Frank Harmon, FAIA

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=397]