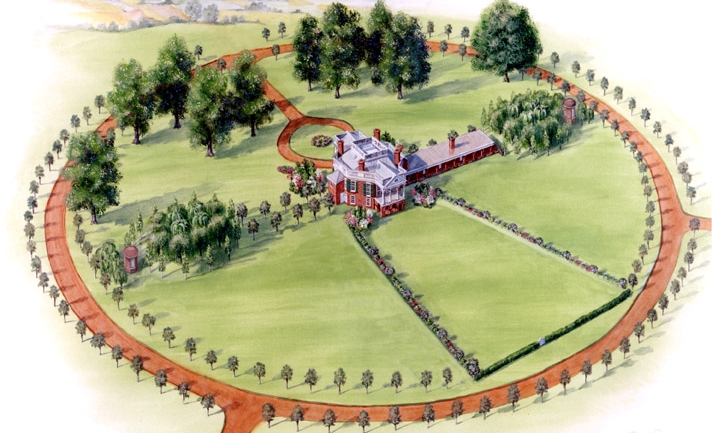

Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest near Lynchburg, Va. is the work of a master designer exploring both geometry and landscape as architectural elements.

By the time it was finished, he’d already designed Monticello in Charlottesville, the state capitol in Richmond, two wings for the White House in Washington, and the campus for the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Poplar Forest, though, is about as perfect a union of natural and man-made forms as the early 19th century could produce.

At the center of the home is a 20-foot by 20-foot cube that’s 20 feet high, a nod to the Villa Rotonda. It’s surrounded by an eight-sided structure. Its original approach was a circular drive all ’round it, flanked on either side by two rows of trees.

“He was fond of French neoclassical landscape design,” says Jack Gary, director of archeology and landscapes at Poplar Forest. “The circular drive allowed visitors to get a rotating view of the house as they moved around it.”

The drive has all but disappeared today, as has a western allee of trees connecting the home to one of two symmetrical mounds flanking the residence. Gary and his crew of archeologists are working now not just to locate the double row of paper mulberries that Jefferson planted between house and mound, but also to replace them.

“The trees were Jefferson’s own take on a Palladian design,” he says. “He was blending landscape with architecture. He used the natural element of trees as actual architectural elements. Using double rows of trees to create a building is pretty unique.”

“It was Jefferson’s perfect house,” says Travis McDonald, director of architectural restoration at Poplar Forest. “He was doing it to please himself. It took him 14 years to get every piece in the right place.”

And come fall of 2011, his allee of paper mulberries will be aligned precisely where he planted them in the second decade of the 19th century.

Can his circular drive, lined with a double-row of trees, be far behind?

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=226]