Since 2010 – the year A+A launched – this website has been covering the ongoing restoration of Poplar Forest, Thomas Jefferson’s rural retreat in Bedford County, Virginia. The project was undertaken by the Corporation to Save Jefferson’s Poplar Forest in 1984. In 1989, the group hired architectural historian Travis McDonald to oversee its restoration and build a team to make it happen. After 34 years of archeology, architecture, research and documentation, the first phase of the villa’s resstoration is complete. I penned a profile of McDonald for Virginia Living’s April issue, and A+A is pleased to post it today:

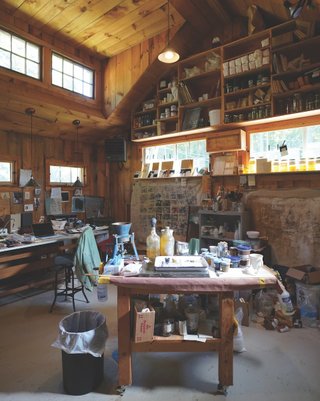

In a late afternoon in September, paint conservator Erika Sanchez Goodwillie pours pigments into a mill that resembles an oversized coffee grinder.

One at a time, she grinds black, brown, and reddish powders, mixing them until she finds her desired color. Then she stirs the compound into a creamy blend of chalk and water, adding glue as a binder. “You let it cool overnight, and it gels,” she says. “We make it fresh, the day before application.”

The final product, called distemper—a French term for “soaking the chalk”—is destined for the interior walls of Poplar Forest, Thomas Jefferson’s octagonal-shaped retreat, which stands a few steps away.

This is no ordinary paint job. Instead, a specialized team, a Who’s Who of America’s historic paint conservators, spent nearly a month formulating and applying Poplar Forest’s original interior colors. Sanchez Goodwillie works closely with Christopher Mills, whose Massachusetts-based firm has recreated museum finishes at historic sites, including Mount Vernon, Stratford Hall, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“We work from 18th-century treatises,” Mills says. “One of them describes distemper as ‘a quivering jelly.’” When applied to the dining room walls, the blackish distemper turns a rich and luminous gray as it dries. The paint specialists had already mixed linseed oil and pigments to cover the cream-colored baseboards, chair rails, architraves, and entablatures. Their brushes of choice? Antiques, made of horse and hog hair. These 19th-century tools deliver a finish that’s as authentic as the paint itself.

An April Celebration

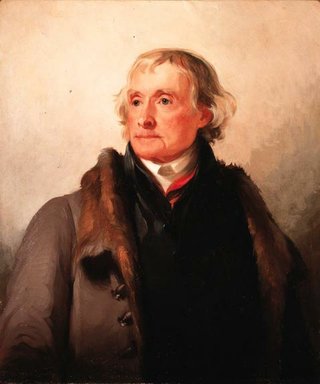

Travis McDonald, Poplar Forest’s meticulous architectural historian, has been overseeing its restoration for the past 34 years—32 years longer than the Corporation for Jefferson’s Poplar Forest had planned when they hired him in 1989.

“When they offered me the job,” McDonald says, “I asked whether they wanted to do it right.” Assured that they did, he set about the task ahead. Three-plus decades later, Poplar Forest will mark the first phase of the project’s completion with a public celebration on April 28, two weeks after Jefferson’s 280th birthday.

In 1989, Jefferson’s original design was almost unrecognizable. Subsequent owners had altered the home over time, adding electricity, running water, closets, and dressing rooms. The spectacular dining room skylight—among the first seen in an American residence—was concealed in 1846 behind a dropped ceiling. “It was totally denatured, including the roofline and even the fenestration,” says Bill Beiswanger, Monticello’s former director of restoration and a member of the Poplar Forest advisory panel.

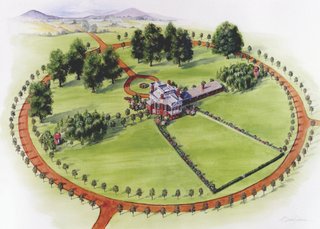

Jefferson was President when he broke ground on Poplar Forest in 1806. He left Washington, D.C., to assist in laying its foundation. By 1809, he’d begun using the house as a retreat from the whirlwind of post-presidential life at Monticello, even as construction continued over the next 17 years.

Once the shell of the home was complete, John Hemings, Jefferson’s slave and brother of Sally Hemings, would work on its joinery. A skilled craftsman, Hemings had been trained first by British joiner David Watson, then by Irish joiners James Dinsmore and John Neilson. Jefferson provided Hemings with his own set of tools and paid him $20 annually to work on Monticello and Poplar Forest.

From Monticello, Jefferson dispatched Hemings to Poplar Forest in 1815, accompanied by three assistants: Beverly, Madison, and Eston. Not only were the men Heming’s nephews, they were also Jefferson’s offspring by Sally, McDonald confirms. Together, their work on the home’s joinery would continue until Jefferson’s death in 1826.

Searching for Clues

The workers’ correspondence with Jefferson left a delicious paper trail for McDonald to savor as he compared details of the existing house—from window hardware to brickwork and decorative trim—through written documentation. “John Hemings knew the language of classical architecture, including the names of moldings,” he says. “After 1815, the letters between Jefferson at Monticello and Hemings at Poplar Forest tell you a lot about what’s happening.”

In 1823, three years before his death, Jefferson turned the home over to his grandson, Francis Eppes, who sold Poplar Forest to a neighbor in 1828. A fire destroyed the interior in 1845, but in the years that followed, the house was rebuilt and updated.

To get Jefferson’s paint colors right, McDonald collected antique paint chips and scraps of plaster from Jefferson’s palette and shared them with Susan Buck, a Williamsburg-based conservator and paint analyst who then cracked the home’s color code. “It’s a medium gray, using lampblack and carbon black pigments,” she says of the dining room walls.

Applying the distemper was the crowning achievement in the first phase of Poplar Forest’s restoration, a process McDonald has nurtured steadfastly over decades, as he strives to recreate Jefferson’s architectural vision. Subsequent phases in the coming decades will focus on the surrounding landscape.

Fielding His Team

And he’d already impressed noted architects Charles Philips and Paul Buchanan, who was known for 30 years, McDonald says, “as the ‘Yoda’ of architectural investigation at Colonial Williamsburg.” Pleased with McDonald’s work on the restoration of the site’s 18th-century Public Hospital Museum, Buchanan had recommended him for the restoration of Richmond’s Wickham House, built in 1812, and now part of the city’s Valentine Museum.

Over time, McDonald’s peer advisors would boast some of the nation’s brightest minds in archeology, architecture, historic preservation, and landscape architecture. Included were experts from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Park Service, and Calder Loth, Senior Architectural Historian from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, now retired. Those advisors chose Jeff Baker and John Mesick to serve as consulting architects, while McDonald hired Andy Ladygo as architectural conservator.

With the team in place, McDonald began two years of painstaking research to assemble the architectural evidence—gleaned from historic documents and the structure itself—that he would need to restore the home. From there, McDonald says, “we had to keep documenting what we found and send that to the architects to draw it up.”

Finding Jefferson

When he removed interior plaster that covered brick walls, for example, McDonald discovered the ghosts of Jefferson’s original wooden trim. He restored the roof with its Chinese railing, a detail described just once—in a letter from Hemings. From there, he moved to the eastern terrace, part of Jefferson’s five-part Palladian scheme, and worked with landscape architects to reconnect a 12-foot-tall grassy mound on the western side with an allée of six paper mulberry trees, just as Jefferson had done.

He then returned to the interior, leaving two eastern rooms with exposed brick, beams, and floors. The rest he restored following Jefferson’s intent—not room by room, but one step at a time throughout the house. The restored dining room entablature—horizontal molding—is based on the Doric order from the Baths of Diocletian in Rome, and depicts the face of Apollo alternating with bucrania, or ox skulls. Architectural historian Calder Loth traced the entablature to a 1650 French book on the ancient and modern versions of the classical orders of architecture, one owned by Jefferson.

Through it all, McDonald kept the doors open to 30,000 annual visitors, who witnessed the work as it progressed. Each summer, from 1990-2019, he ran a two-week restoration field school for handpicked students. More importantly, he assembled a paper trail of documentation, including two books, for future historians to peruse and learn from.

Now faithfully restored, the building resonates with Jefferson’s presence. On a shelf near his Campeche chair, a pair of his glasses sits folded on top of a book, as if he’s just set them aside.

Do the results match McDonald’s vision from 1989, the year he arrived? “Of course not,” he quips, adding: “Jefferson was in hiding.”

Now that the original architecture has been restored, that’s no longer true. “Travis is like a horse whisperer,” says fellow architectural historian John Larson, a member of the Poplar Forest advisory committee who’s also overseen restorations at Old Salem Museum and Gardens in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “He looks at a building, listens to it, and reads it like nobody I know.”

McDonald understood how long it took to build Poplar Forest, and he soaked up the layers and levels that had unfolded in every room. Then he transformed the building to bring Jefferson—and his most private spaces—back to life.

For more, go here.