Here we have a feature I penned for the online edition of Metropolis, which was published yesterday. It describes the intricate cut-paper work of Christina Lihan, the handmade cotton tapestries of Marilyn Henrion, and the Puerto Rico-inspired oil paintings of Enoc Perez. We’re pleased to re-post it on A+A:

Three artists, each working in different media, have independently discovered their true north—in the world of architecture.

One reimagines the bas relief in cut and layered paper, creating huge installations and smaller shadow boxes to mimic familiar landmarks. Another shoots photographs of old and new buildings, prints them as fiber art on organic, polished cotton, then hand-stitches them for the human touch. The third works in oil on canvas from his New York studio, looking back to the modern architecture of his native Puerto Rico.

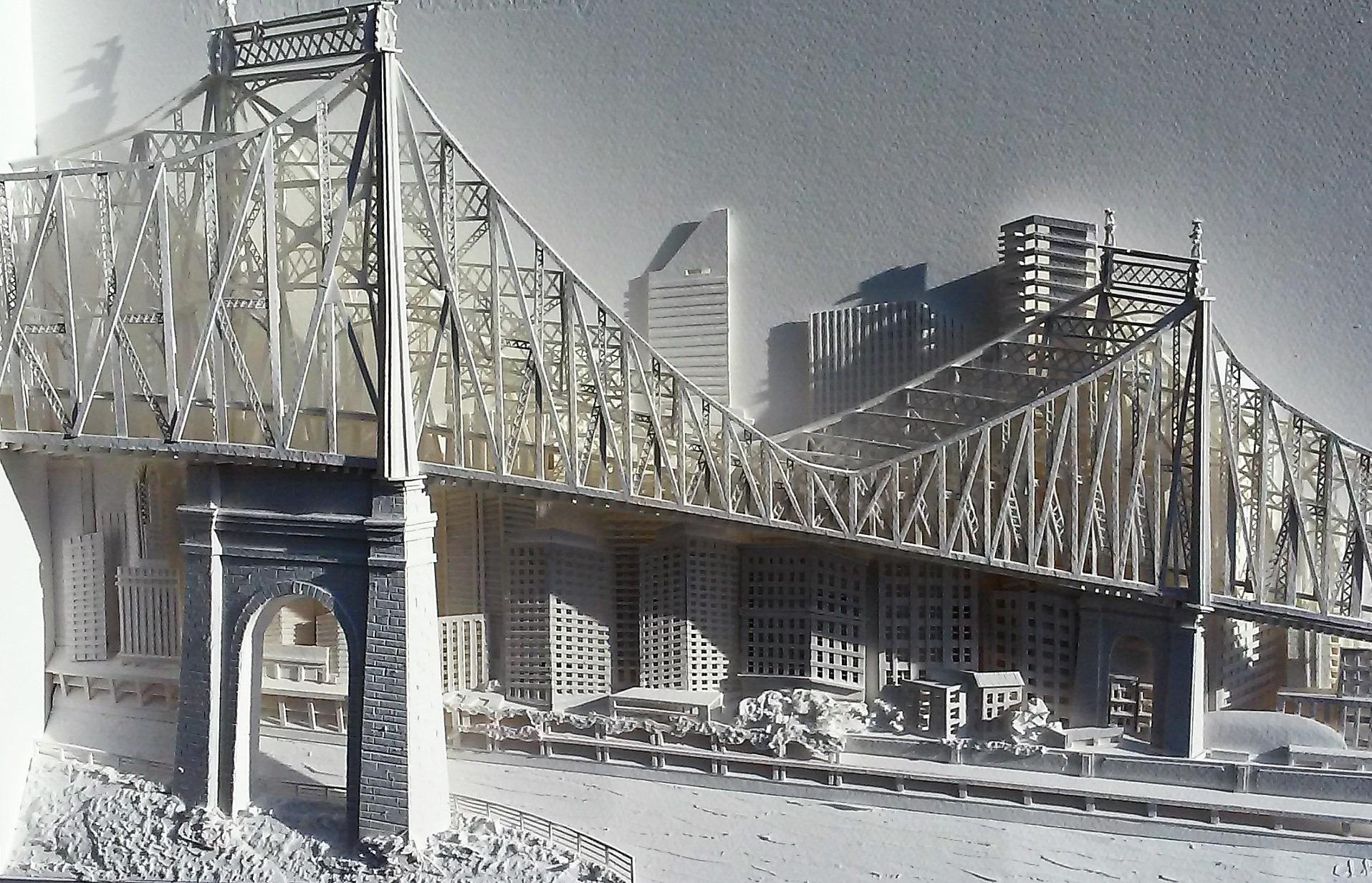

Christina Lihan learned to work with cut paper in a design class as a first-year architecture student at the University of Virginia. She earned her graduate degree in architecture from Columbia in 1992, then began practicing in South Florida and Atlanta. All the while, she was creating cut-paper sculptures on the side.

She jumped into making them full-time in 2008, piling on sheet after sheet of 300-pound watercolor paper from Fabriano in Italy. “It cuts like butter,” she says. “You can score it, put water on it, then shape it— and it holds.”

Her first major commission was in 2006 for the lobby of the 28-story Spire Condominiums in Atlanta. In 2016 she installed a major cityscape on the ground floor of New York’s Flatiron Building. Her latest works include eight pieces in the lobby of England’s new Londoner Hotel, and another for Biltmore House in Asheville, North Carolina.

“She’s the real deal,” says New York architect Daniel Frisch, who owns two of her shadow boxes. “I don’t think any other artist is doing what she does.”

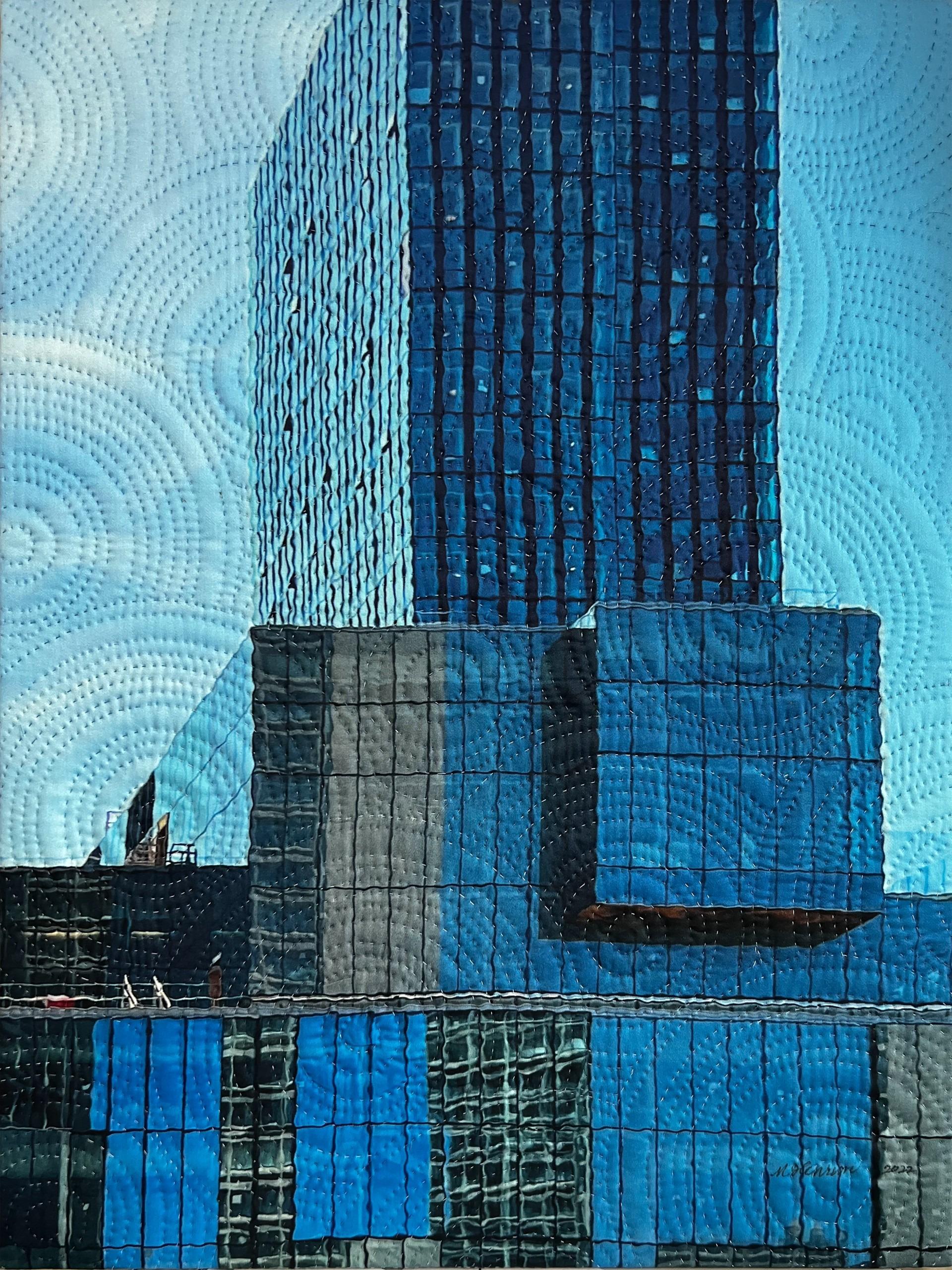

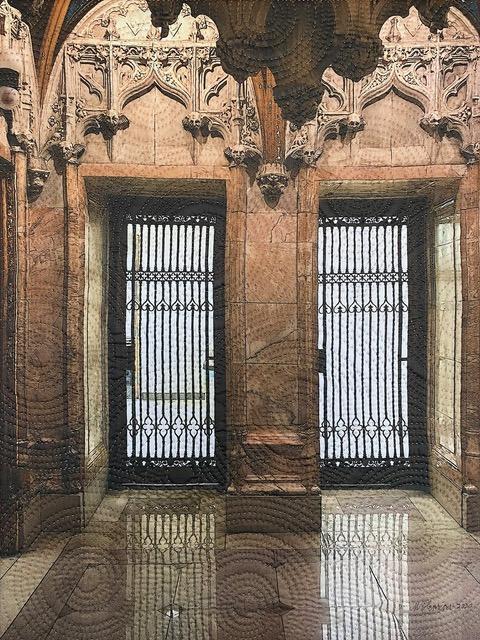

Marilyn Henrion is a 1952 graduate of Cooper Union who started out as a painter, took time off to raise four children, then began creating fiber art in the 1970s.

Manmade structures are her preferred subject matter. “The hand of man on the environment is interesting to me, kind of like ‘Kilroy was Here,’” she says. “I’m 90 years old—and now I have something to leave behind.”

At the moment, she’s living in Plano, Texas, but she maintains her 23rd-floor apartment overlooking Greenwich Village just below Washington Square, where she can see from the Hudson to the East River. “All my life, that’s what I’ve seen in urban architecture,” she says. “I’ve done tapestries of all these big buildings, plus the High Line.”

Enoc Perez is a painter born and raised in Puerto Rico. His father told him that if he wanted to study art, he should go to New York. And he did—graduating first from Pratt Institute in 1990 and then from Hunter College in 1992.

His first order of business was to establish his own New York language of painting. “I set out to make a painting through the process of printmaking like Warhol used silk-screening in his painting process,” he says. “I thought you should have a relationship to what came before you.”

Eventually, he began to show his work, little by little, in New York galleries. But his “Eureka!” moment arrived on 9/11, with the collapse of the World Trade Center. “I found that to be painfully significant to me about architecture,” he says.

Today, at age 50, he’s moved on to painting the tropical modernism of his native land in what he calls the second chapter of his career. “The natural landscape and architecture of Puerto Rico are almost like an identity for me,” he says. “I’m telling stories of the Caribbean that never get told—and for me, that’s a cool thing to do.”

Like Lihan and Henrion, he’s creating art from designs that delight him.

For more, go here.