(Today’s post is the first of a number planned to explore a new exhibit of Andreas Palladio’s drawings at The Morgan Library and Museum in New York. A peerless display of the Italian master’s work, it features drawings never seen before in the United States.)

The drawings by Andreas Palladio at The Morgan Library and Museum have arrived in New York via a circuitous route over seven centuries. But for the efforts of a dedicated group of afficionados, it’s a near wonder that they are here at all.

Their history reaches back to 1414 and Poggio Bracciolini’s discovery, at the monastic library of St. Galen in Switzerland, of a manuscript copy of “De architectura,” the treatise written by Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century AD

“That was long before Palladio’s lifetime,” said Dr. Irena Murray, co-curator of the exhibit and also the Sir Banister Fletcher Director of the British Architectural Library at the Royal Institute of British Architects. “But later, one of his patrons wanted to publish a new edition of the manuscript.”

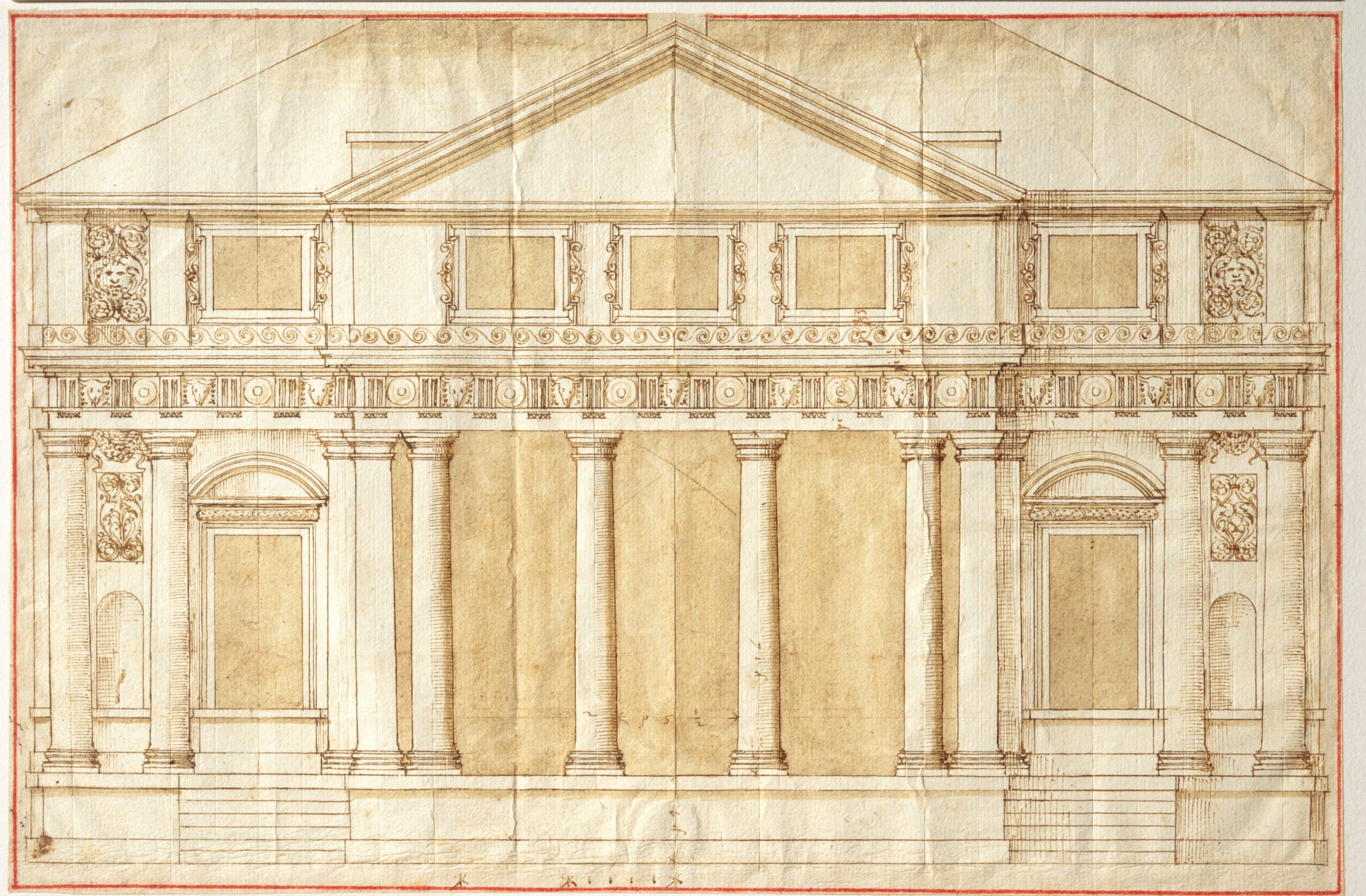

The Vitruvius work called for illustrations, but lacked them. So in 1556, Palladio’s friend and patron Daniele Barbaro engaged him for the drawings in a book to interpret the Roman’s writing.

“That’s our copy in the exhibition,” Dr. Murray said. “It’s edited by Barbaro and illustrated by Palladio. Our copy was owned by a 17th-century French architect and theorist whose signature is on the book. He was the first person to translate Palladio into another language, in 1650.”

The Royal Institute of British Architects came by many of its works by Palladio through the efforts of British architect Inigo Jones, who traveled twice to Italy in the early 1600s, returning with 150 drawings sold to him by either a Palladio collaborator or his son. “When he brought them to London, he made them the focus of his social circle of painters, sculptors, architects and like-minded people at court,” Dr. Murray said. “It was the birth of Anglo-Palladianism.”

In 1719, Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, brought back the second half of the Royal Institute’s collection. The Institute’s web site notes that, according to tradition, these had been found in a trunk at the Villa Barbaro at Maser, where Palladio had died in 1580.

The rest is history. “We have the largest collection of Palladio drawings in the world – 330 of them,” Dr. Murray said.

There were plans for an exhibit at the National Gallery in Washington to mark the 500th anniversary of Palladio’s birth, until the world economy slipped off its rails in 2008. Then Charles Hind, co-curator of the drawings, came up with the idea for a smaller exhibit of a different group of Palladio’s drawings – the ones that influenced early architecture in America.

The Institute found willing supporters in the Richmond, Virginia-based Center for Palladian Studies in America. “It’s so exciting to get to know people who love Palladio in America,” Dr. Murray said. “The center as a group was one of our supporters, so we owe them a lot.”

The rest of us, though, owe them all much more.

Next: Palladio’s influence on 18th-century American architecture.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=98]