Educated at Princeton and the École des Beaux-Arts, Marion Sims Wyeth arrived in Palm Beach at precisely the right moment.

An intern for a New York architecture firm, he visited in 1919 to look at one of the houses he’d worked on. And he found a town filled mostly with wooden, Shingle-Style homes, says Palm Beach historic preservationist Dr. Jane S. Day.

“There are four left,” says the author of “From Palm Beach to Shangri La: The Architecture of Marion Sims Wyeth” (Rizzoli, 2021). “Three are at the Breakers and one is next to Whitehall, Henry Flagler’s former residence.”

He also found one other practicing architect: Addison Mizner.

“Mizner offered him a job when he first got there, and that would have been the sane, conservative thing to do,” she says. “But he doesn’t do that – he starts out on his own.”

Thanks to his Alabama-based family of doctors (both his father and grandfather served as head of the AMA), he landed a commission for the Good Samaritan Hospital, the first in West Palm Beach. It ushered in a style he described as “quiet, subdued, and rational.”

Those terms certainly apply to the design of his own office, designed in 1925. “The design of his office building is brilliant,” she says. “The first floor has a small lobby, and then you go upstairs to his second-floor office, and on the third floor is his staff, with an interior courtyard behind his space.”

Serendipity played a role in his first residential commission – for Marjorie and E. F. Hutton. “He was walking down the street with the manager of the Everglades Club, and he met the couple as they were overlooking a lot at the club’s golf course,” she says. “By the end of the day, he had a commission and becomes the realtor – on a handshake and a gentleman’s agreement.”

Their home at 17 Golfview Road was to be called Hogarcito, or ‘Little House.” Designed in the Spanish Mediterranean style, it’s more than 10,000 square feet, and features an open-air colonnade. It was completed in 1921, and opened the door to a spectacular series of homes Wyeth designed in Palm Beach and West Palm Beach.

Among them were the master planning for Mar-a-Lago, also designed for his friend Marjorie Hutton, later known as Marjorie Merriweather Post after her divorce from Ned Hutton. She would hire Hollywood set designer Joseph Urban for the over-the-top decor at Mar-a-Lago.

“Wyeth did the bones of the house, the central cloister and the way the wings came off center, and Urban did the ornamentation,” she says. “There’s nothing subtle and rational about that house – it’s a Hollywood set, and that’s what it’s being used as now.”

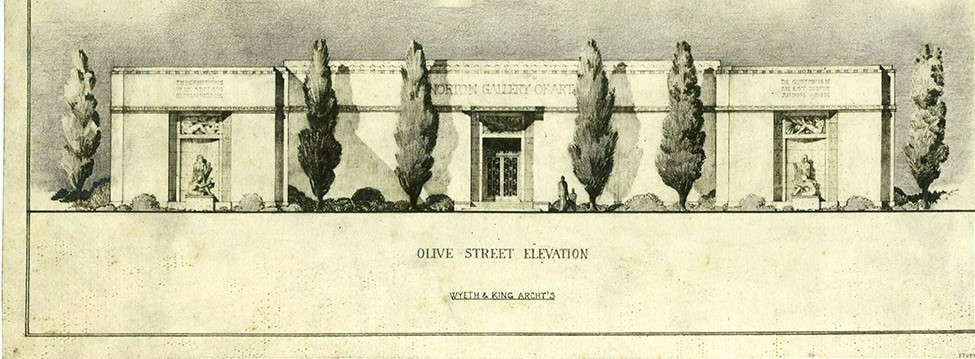

More residential work would follow, including Shangri La for Doris Duke, and La Claridad for Mrs. Clarence Geist. Wyeth also designed the Seminole Golf Club in 1929 – and a restrained, Art Deco Norton Museum of Art in 1941. That museum was restored to its original charm by Foster + Partners in 2019.

In 1955, he designed the Florida governor’s mansion, inserting it into a rise on site. “It looks like it’s two storie, but from rear approach you can see it’s three,” she says. “It’s a more complicated building than you think it is on first approach – Wyeth said it was the most complicated one he worked on.”

He lived from 1919-1982, retiring in 1973. “He was still living behind Mar-a-Lago,” she says. “Marjorie built a gate so he could come across and play golf.”

And why not? This was an architect who lived, worked and designed as if he were the Prince of Palm Beach.

Which, in fact, he was.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2383]