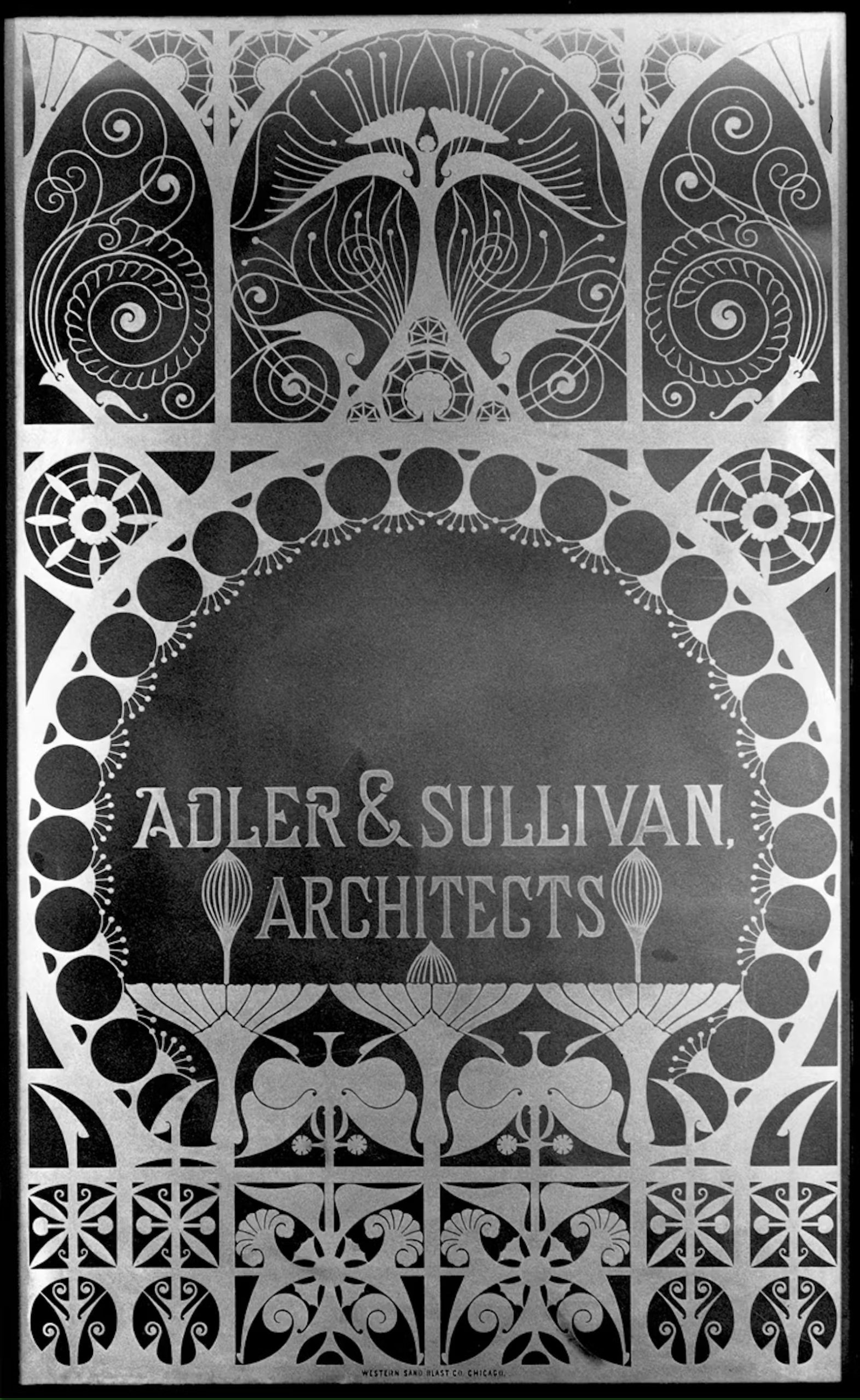

I was pleasantly surprised last week when Dwell’s online edition reposted a book review and interview I penned for the magazine back in 2011. It chronicled the publication of a book about Chicago photographer Richard Nickel’s efforts to record the architecture of Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan. The feature article also includes a Q+A with Ward Miller, who co-authored the 2010 publication of “The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan” with John Vinci. A+A is pleased to repost the start of that feature here, with a link to the complete interview at its end:

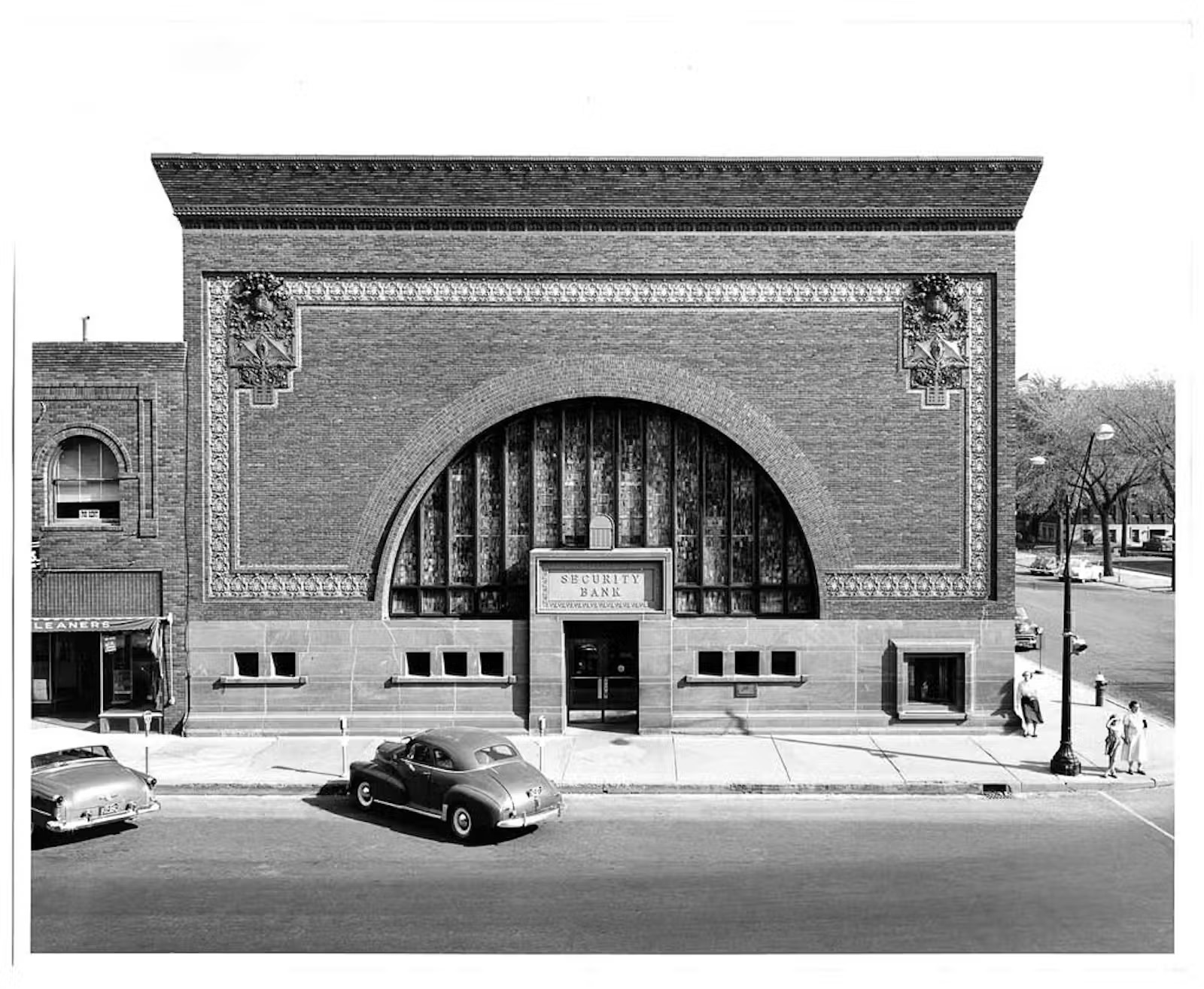

In 1952, a photography student named Richard Nickel began to document the works of Chicago architects Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan within the context of aging neighborhoods, crude remodeling, and outright demolition. Of the 256 buildings designed by the late-19th- and early-20th-century architects, both as a team during their 15- year partnership and as individuals, only about 30 still stand. Most were demolished in the ’50s and ’60s during the age of urban renewal. Of these, the majority were in Chicago, where their firm, Adler & Sullivan, was based.

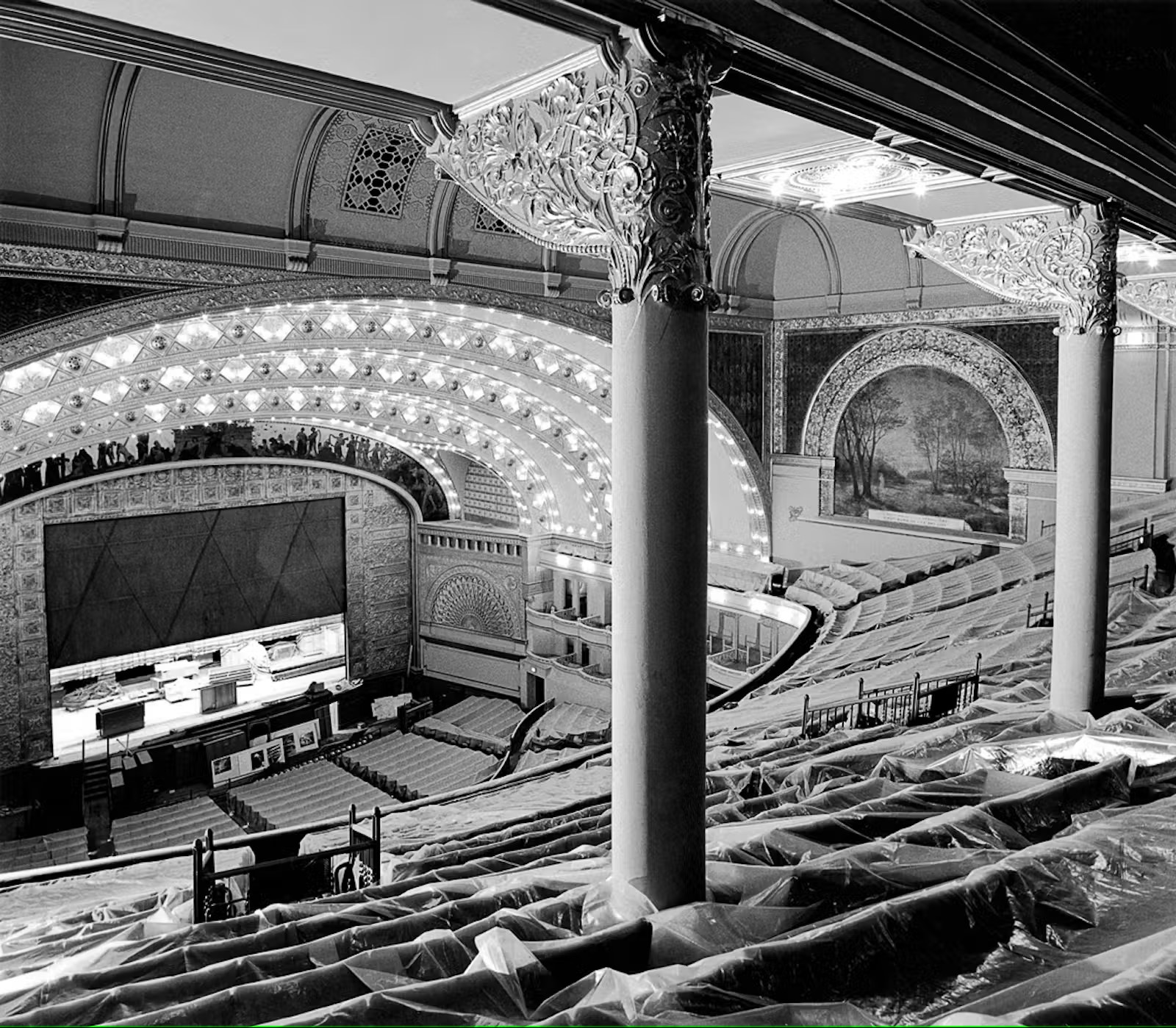

Though Nickel’s documentation of Adler & Sullivan works began in a graduate-level photography course at Chicago’s Institute of Design (now the Illinois Institute of Technology) instructed by photographer Aaron Siskind, he continued cataloging the architects’ projects into the early ’70s, with plans to produce a book. In 1972, however, Nickel died in an accident at the demolition site of the Sullivan-designed Chicago Stock Exchange building. Upon his passing, Nickel’s friends and colleagues formed the Richard Nickel Committee to retrieve his archive and continue his project research. In late 2010, the University of Chicago Press published The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan, a hefty book with more than 800 photographs by Nickel, Siskind, and other noted photographers, as well as architectural plans and essays that catalog the oeuvre of Adler and Sullivan (the latter often called the “father of skyscrapers” and “father of modernism”).

Chicago preservation architect Ward Miller was the executive director of the committee that brought Nickel’s work to fruition and coauthored the 2010 publication. I talked to him about the significance and influence Adler and Sullivan’s buildings, and why Nickel’s documentation of them is something everyone ought to know about.

Dwell: What was the relationship between Adler and Sullivan during their 15 years of practicing together? Their roles? How did it affect their architecture?

Ward Miller: Adler & Sullivan are most associated with being an innovative and progressive architectural practice; forwarding the idea of an American style and expressing this in a truly modern format. Their work was widely published and at the forefront of building construction. Their buildings—especially their multipurpose structures, like the Auditorium Building and Auditorium Theater in Chicago—were unequaled. The expression of a tall building, its structure with a definite base, middle section or shaft, and top or cornice was a new approach for the high-building design. These types of tall structures developed into a format. It’s most evident in expression in the Wainwright Building in St. Louis and later the Guaranty Building in Buffalo, New York. Even today, the vertical expression of a building employs these design principals.

For more, go here.