The Assembly, a statewide magazine that publishes deep reporting on power and place in North Carolina, recently ran a feature I wrote about a small town’s resilience from major flooding. After being overcome by Hurricane Florence, tiny Pollocksville used grit, grants and gumption to recover – and created a model for responding to rising water, especially after Hurricane Idilia in recent days.

By J. Michael Welton

it’s a summer afternoon in Pollocksville in Jones County, 14 miles southwest of New Bern. A cool breeze stirs the leaves of sycamores along the banks of the Trent River. Near a boat ramp and kayak launch, cars and trucks rumble across a steel-truss bridge, slowing on U.S. 17 Business to cruise the town that’s home to just 275 people.

A glittering-blue bass boat drifts quietly upstream, powered by a bow-mounted trolling motor. Its lone fisherman slings a topwater lure near the far bank, slipping his line over cypress knobs above the surface. The Trent’s about 50 feet wide here, and 10 feet deep at mid-channel.

Today, this river’s a gentle portrait of slow-moving serenity. But in September 2018, it was anything but calm. When Hurricane Florence arrived early on September 14, the Trent began its rise up and over the boat ramp, the kayak launch, and the bridge—then lumbered 2,000 feet into town.

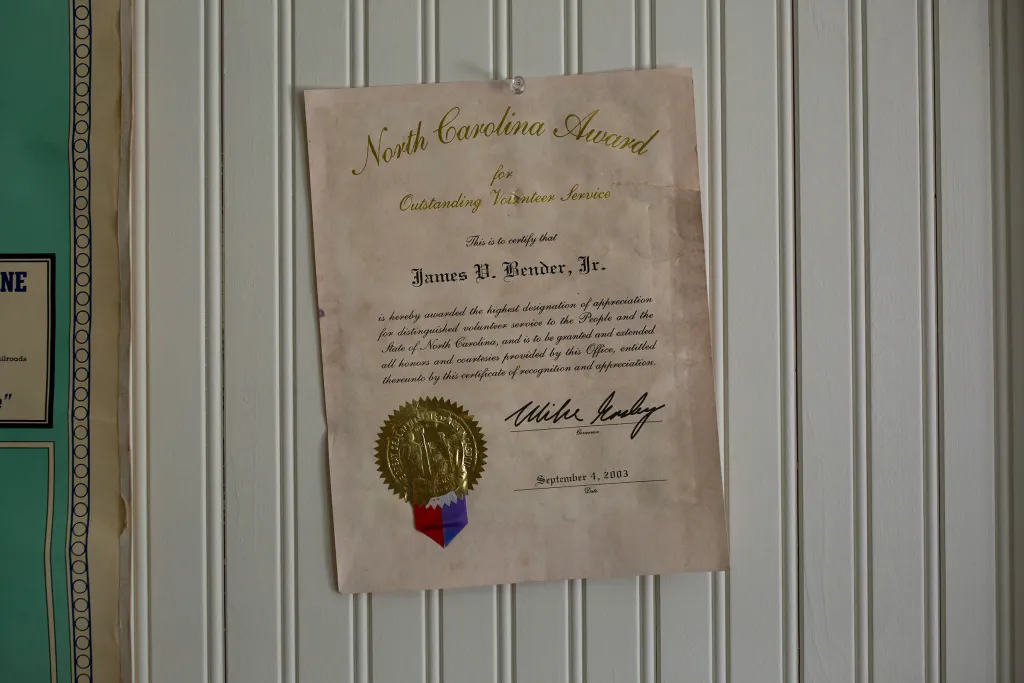

“We just got whomped,” Jay Bender, who’ll mark his 41st year as Pollocksville’s mayor in November, told The Assembly.

Florence also flooded New Bern with 3 to 4 feet of water, and backed the Neuse River up into the Trent. On September 15, Pollocksville was pummeled by a 10-foot storm surge from downstream. Three days of rain unleashed torrents of upstream water and submerged much of the town. On September 17, the river crested higher than 20 feet.

Sixty-nine homes and 14 commercial structures were flooded. Town hall, on the banks of the Trent, saw water up to its eaves. The post office stood in 5 feet of water. Miraculously, no one was injured or died.

The town was without power for 11 days. Sixty percent of its citizens were evacuated or departed on their own, including town commissioner Nancy Barbee. She’s a lifelong resident who lives in the home her parents bought during the Depression, in the center of town.

Water had reached her driveway during hurricanes before, but didn’t venture into her home because floods never reached the level of a 100- or 500-year storm. Florence, however, was a 1,000-year hurricane.

Barbee’s home may have been elevated 4 feet above ground, but 2 feet of water still sloshed across her first floor. “The New York City police came in a pontoon boat and picked me up,” she said.

Like most other residents, she would leave for six weeks. But she was determined to come back, clean up, repair the damage, and rebuild her town. “Our attitude was: ‘Stay and make the best of it,’” she said.

A Waterlogged Mess

The mayor’s home, once his grandfather’s, sits on higher ground untouched by floodwaters. When Florence hit, he and his wife took his mother, 95 years old at the time, to their still-intact beach house and came back five days later. There was no gasoline, so most generators couldn’t function, but his was powered by natural gas. It ran his computer and charged his phone.

Bender made a “zillion” calls to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the state Department of Emergency Management. His community was a waterlogged mess, exacerbated by the fact that all five town commissioners had left. “My clerk lost her roof, my maintenance man couldn’t get to town, and neither could our water/sewer operator,” he said.

But he did have influential contacts, and he used them. Among the state agencies he reached out to were the governor’s office, the attorney general’s office, the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, the Wildlife Resources Commission, and the Golden Leaf Foundation. All responded positively, though there were questions.

A former three-star general friend asked him if he would even still have a town. “But our folks are resilient,” Bender said. “They refused to give up.”

The Coastal Dynamics Design Lab in N.C. State’s College of Design became an important resource. It’s a group of six landscape architects who develop resiliency strategies for towns like Pollocksville.

Unlike large municipalities, these small towns aren’t flush with resources or staff to deal with disasters. Working with elected officials, town staff, residents, and business owners, the lab analyzes flooding, land use, and transportation networks.

They look for nature-based landscape solutions like restoring stream channels and wetlands to better absorb rainfall and floodwaters, especially in areas altered by development in floodplains. They also look to cultural and natural resources, like riverfront recreation, for potential economic development.

The lab’s budget is tiny—about $600,000 annually. It doesn’t take a cent from the communities it serves, but works with them to write, manage, and implement state and federal grants.

After hearing about Pollocksville’s fate from a friend of the town, lab director Andrew Fox and associate director Travis Klondike traveled to meet its mayor and commissioners. “They came, we told them our vision, and they started working on it,” commissioner Barbee said.

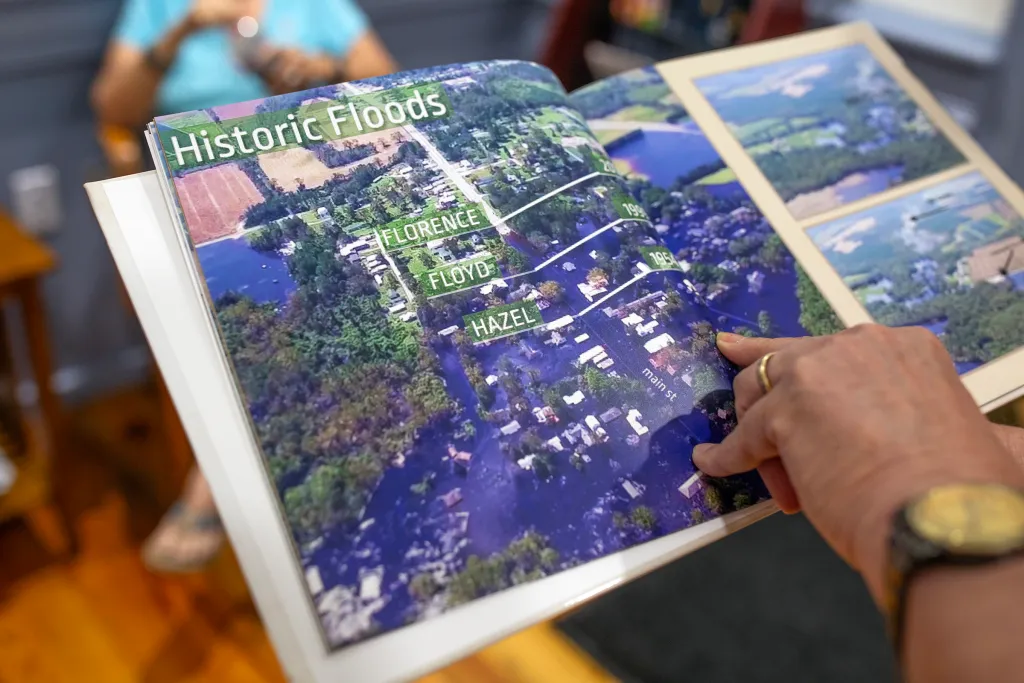

The result was a 120-page document called a floodprint that lays out a phased development to make Pollocksville resistant to future storms and hurricanes.

It reinforces Jones County’s mandate requiring all new and substantially improved structures be elevated 4 feet above base-flood elevation. It offers solutions for rebuilding the riverfront with bioretention areas and native plantings. And it proposes new sidewalks, plants, and rain gardens for the town’s five-block-long downtown.

To date, Pollocksville has received $15 million in grants from state and federal sources.

Where the town hall once stood on the riverfront, a mix of bioretention and native wetland plantings now flourish on an acre of land. When the river overruns its banks, water is held there, with roots from trees and plants acting like sponges. Those plants also bring in more animal life—pollinators, butterflies, birds, bats, flies, and beetles.

“That support is really important to the biodiversity of the region and enhancing native ecosystems,” said Leslie Bartlebaugh, a lab extension specialist.

The new riverfront area is now laid out with a boardwalk, sidewalk, and seat wall. Funds for the project totaled $240,000, with $114,00 from an environmental enhancement grant from the North Carolina Department of Justice, and the balance from a North Carolina Emergency Management grant. Restoration of the boat ramp was covered by a grant from the state Wildlife Resources Commission.

For more, go here.