A recent issue of Ocean Home magazine featured an article I wrote about a new home in Coconut Grove, Fla. Designed by Jacob and Melissa Brillhart, it draws on their firm’s deep commitment to sustainable design – and its Corbusian roots. We’re re-posting it here on A+A today:

Three floods in 12 years led Brad Hermanto an abrupt epiphany about his Coconut Grove home: “After Hurricane Irma in 2017, there were three to four feet of water in the house and I said: ‘I’m over this,’ and I decided to raze the house and build a new one.”

“I contacted Jake,” he says. “And I discovered that what I wanted and what he could do gelled.” Herman wanted an urban industrial look, with materials that could stand up to South Florida’s rising waters, steamy climate, and salty air. Since the Brillharts had been practicing their savvy brand of tropical modernism since 2007, they were a natural choice. “We bounced some ideas off each other,” he says. “It came down to concrete, glass, and steel.”

It was a smart move. Miami’s sea level is expected to rise 10 to 17 inches over the next few years. There’s a FEMA mandate that a new home’s first floor must rise 12 feet above grade. So the initial design idea was a no-brainer: Build the house above any flood threat.

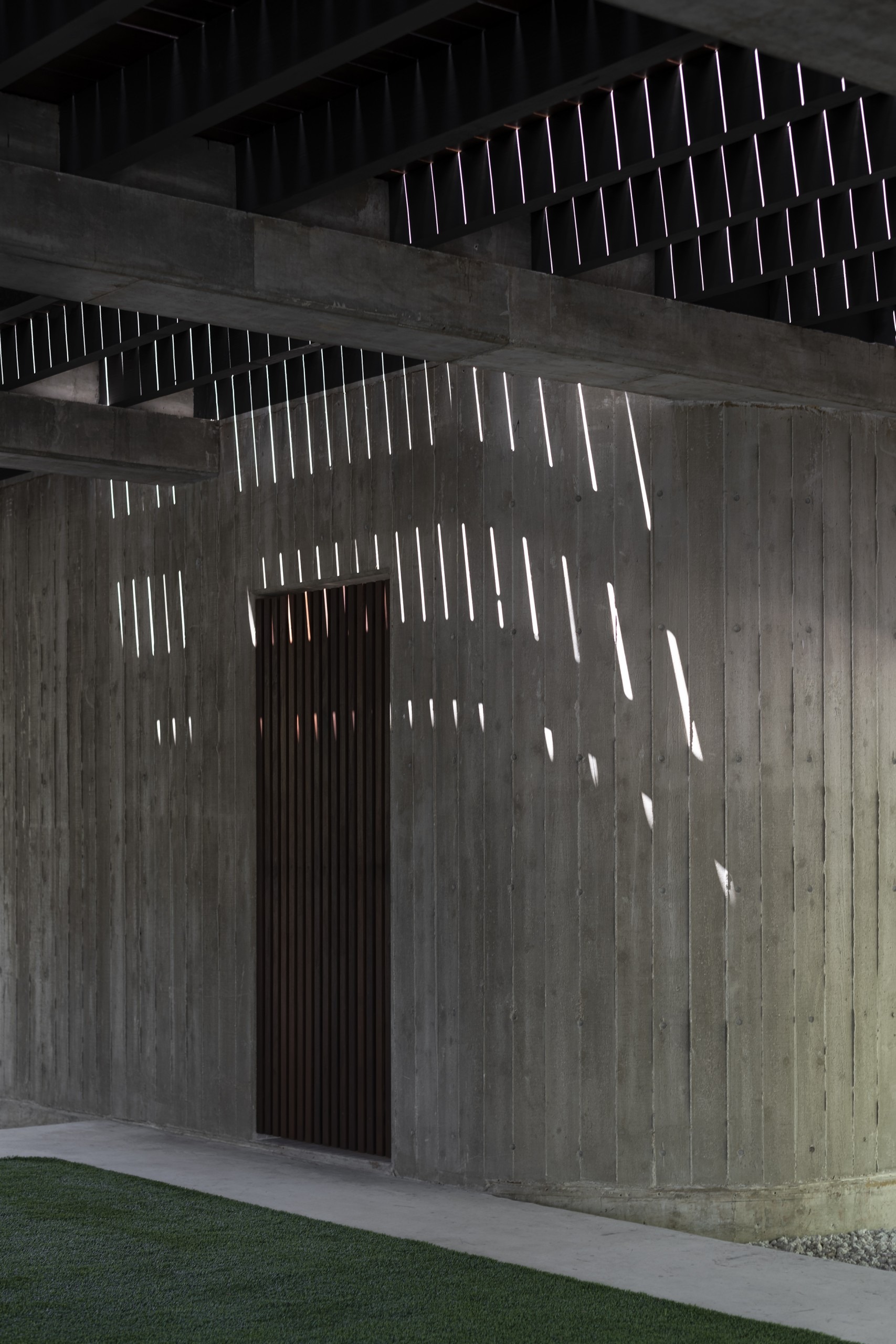

Stilts were one possible option, but Herman demurred—and his architects looked back to Swiss modernist Le Corbusier. “This was built with three Corbusian sculptural columns, or cilopes, at the bottom in a grid,” says Jacob. “There’s a stiffness to them, and they’re large enough to house storage space in the garage.”

Then there’s a series of slender steel columns for further support of two upper levels. The ground floor is also home to a small, artificial-turf-clad soccer field for Herman’s son. Now when sea waters rise, damage will be minimal.

“The bigger idea is that the ground plane is sort of an afterthought,” Brillhart says. “You come in past a coral rock wall, saved from the original homesite, to concrete piers that hold up the house. There’s practicality, but it’s beautiful.”

Herman now drives under his house and ascends a stairway to a breezy, open-air deck and lap pool. “The deck on the first level with the pool is 3,000 square feet, and we added another 500 square feet on the porch above,” says Melissa Brillhart. “It’s a total of about 6,000 square feet, with the understory deck and the porches above.”

Besides the Brazilian Ipe deck on the first level are enclosed living and dining areas, as well as kitchen, gym, bath, bedroom, and powder room. The master suite, two bedrooms, and two baths are above that. “Every bedroom and every living space has outdoor space connected to it,” Jacob says. “It’s only one room deep, so they’re immediately connected with balconies, decks, and windows—it’s an important part of living in the tropics.”

The material palette was limited but imaginative. “I wanted a minimalistic house, but not one without any warmth,” Herman says. “The entire interior upstairs have vaulted wooden ceilings, and there are exposed glass and concrete walls.”

The concrete was board-formed from Western cedar. “That gives an incredible texture to the home, so it doesn’t look like a concrete box,” he says. “People ask: ‘What kind of wood is that?’ because it has the texture of rough cedar.”

The Brillharts worked with general contractor Martin Rodriguez to bring the concrete to life. Trained as an architect, Rodriguez sees eye-to-eye with Jacob. “We have a real cohesion,” Rodriguez says. “And we really care about our concrete—it has to be perfect, poured at the right temperature on the right day.”

The roof is steel-framed and copper-covered, with overhangs kicking out three-and-a-half feet so rain doesn’t run down the structure’s side. Insulation was added below the copper to keep it cool, with plywood beneath. “It’s an Oreo sandwich with black plywood, white high-density foam insulation, and then the roof,” Herman says. “It’s seven inches thick and rated R-40—it’s incredibly efficient and it gives us a nice, thin roofline.”

In essence, as Melissa Brillhart says, the structure itself is the architecture. “All our projects use the chemistry of space as ingredients—they create atmospherics that affect us emotionally,” she says. “You can feel the site, weather, material, light, color, craftsmanship and local hands doing the work.”

Adds her husband: “You feel the weather with the overhangs,” he says. “The house is ready for the rain, and you feel the wetness.”

Then there are the serendipitous beams of light that penetrate, cathedral-like, between deck boards. “It’s a happy accident,” he says. “The natural world did its thing.”

But it had huge help from a material-driven team of architects.

For more, go here.

Photography by Stephan Goettlicher