Alphonse Mucha, the artist synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement of Paris in the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, was not exactly a fan of the movement.

Nor was he French.

“He said there is no such thing as new art, but that art is eternal,” says Michele Frederick, associate curator of European art at the North Carolina Museum of Art. “It was more that his artistic language is universal harmony and timeless beauty – he was interpreting it.”

Mucha was born in 1860 in what was Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire ruled by the Hapsburgs, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His home now is known as the Czech Republic. “He spoke French and Czech, and there’s Latin in some of his posters too, but they’re mostly in French and Czech,” she says. “He spoke English as well, and lectured in the U.S.”

In October, Frederick and the NCMA opened an exhibition that explores 120 of the artist’s objects, including photographs, drawings sculptures, prints, watercolors, paintings and decorative arts.

His models were stunning beauties. “He used professional models – they would pose in his studio and he would hand-draw them and sometimes photograph them and then transfer the images to posters.” she says. “He was interested in capturing images of his female models directly.”

His most famous was actress Sarah Bernhardt, who actually discovered Mucha – and launched his career like a rocket in 1895. “She commissioned a poster for one of her plays, and on New Year’s Day in 1895 the poster appeared,” she says. “She signed him to a contract for posters and sets and costumes, and then he signed a contract with a printer for advertising commercial products.”

Though known to many as a commercial artist, Mucha was in fact blurring the lines between commerce and fine art. “He did fine art with a commercial aim, and art for the people at a time of art for art’s sake – he would not only break down art barriers, but economic barriers too” she says. “And technology like lithograph prints made his work available to a larger audience, so he saw what we would categorize as commercial art as just art.”

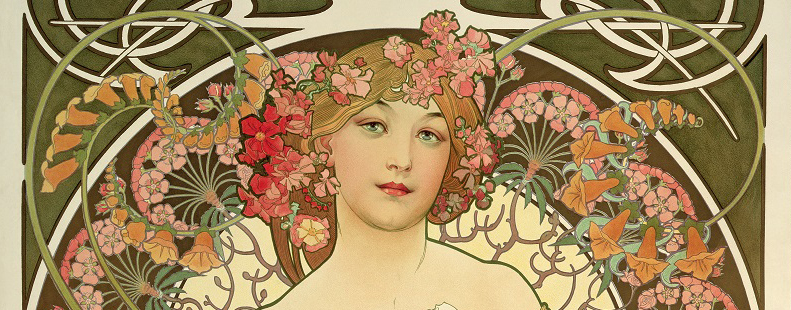

While other artists were making advertising posters that were bold and bright, his color palette was distinctively different. “His is a muted, subdued palette that was unique to him,” she says. “He wanted to create harmony over something bold in color, so he used a more gentle palette – there were not electric reds and yellows.”

Mucha’s overarching belief was that a work of art should create harmony in the world. He portrayed powerful, monumental women surrounded by curvilinear, floral lines, to create something beautiful and harmonious. “He thought beauty contributed to a unified world and peace,” she says. “He was inspired by the natural world – it was a driving force, even in Paris, that the social good of his art be a positive social force.”

His art was also his way of preserving the Slavic culture. His region had been invaded by the Hapsburgs and that culture was falling under the umbrella of the Germans. So, in France, he asserted his cultural heritage. “The headwear and gowns were patterned after formal dress of the Slavic region,” she says. “He portrayed universal social good, but protected the Slavic culture also – he’s associated with the French now, but really his work is Slavic or Czech.”

An artist working toward timelessness in a moment that is his own time and place, Mucha eventually returned to his homeland, dying in 1939 – the year Germany invaded Czechoslovakia.

The exhibition closes on Jan. 23. Don’t miss it.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2367]