Before there was the Internet, or television or even radio, there was the residential library.

And George Washington Vanderbilt’s library at Biltmore Estate in Asheville was state-of-the-art for 1895.

“It was a showplace for his astonishing collections and a space for entertaining,” says Leslie Klingner, Biltmore’s curator of interpretation. “It was the television of the 19th century – he’d read aloud here after dinner.”

Accessible via the home’s tapestry hall, the library faces southwest on one side, opening out to a loggia with breathtaking mountain views, and to the north on another, where a courtyard full of the garden’s original wisteria still climbs its trellis.

But the space itself, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, also endures. Not only are 10,000 of Vanderbilt’s volumes on display here, but some of his favorite collectibles too. “The busts around the room are of French royalty, writers and composers,” she says. “The three-foot globe – and there aren’t many of that scale anywhere – was what President Obama was drawn to when he was here.”

Three ceramic Ming Dynasty fish bowls have been placed strategically about the room. Two are blue and white, and the third contains rare polychrome elements of yellows, browns and red. Each depicts the five-fingered dragon, a symbol for the emperor, as well as flaming pearls, a cipher for enlightenment.

“Goldfish were a symbol of abundance and power – they’re almost identical words in Chinese,” she says. “They were raised in ponds and brought out on display in aquariums like these.”

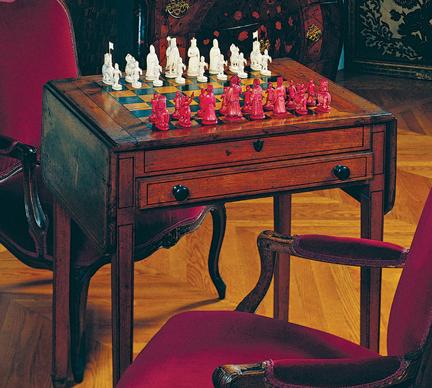

Perhaps the most intriguing item in Vanderbilt’s library, though, is Napoleon’s chess set, used by the French emperor before his death in exile on the island of St. Helena. “I think George was a Napoleonic collector, and that’s interesting, particularly for an American at that time,” she says. “For his wedding gifts he received a bust of Napoleon and a snuff box that once belonged to him.”

According to Biltmore archives, the chess set is 19th-century ivory from China. It rests on a gaming table in which the heart of the emperor was said to have been placed after his death at St. Helena. Vanderbilt acquired the set and table between 1880 and 1889.

Peering down on all in the library is an 18th-century Pellegrini painting known as “The Chariot of Aurora.” It once adorned the Pisani Palace in Venice. “Hunt probably found it and collected it,” she says. “The canvas was cut into 13 strips, shipped here, and then basically nailed up.”

The ceiling painting depicts dawn and the light of learning.

That’s a central theme for Vanderbilt’s life and home alike. On his bookplates – and above the black marble mantle of his fireplace where he once read aloud to guests – is the central motif of the man’s existence. “It’s the lamp of wisdom,” she says. “It’s a symbol of enlightenment.”

It’s brought to life in three dimensions by the Aladdin-like lamps around the library, illuminating all within it – including the flaming pearls emblazoned on the Ming dynasty emperor’s fish bowls.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=207]