A constrained site led architect John Sather through months of problem-solving for a new clubhouse at Lake Tahoe.

To the south is a golf course. To the north, a nature preserve. To the east is a residential complex. And to the west lies Lake Tahoe itself.

Then there was the easement that runs through the property, plus the mountain of lake regulations to abide by, and the environmental groups to be satisfied.

“It took us a year to figure out how to really work through all that,” the senior partner at Scottsdale-based SWABACK says.

But in the end, the graduate of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture took the most direct course: He followed the sun.

“The view is to the west and that’s where the most dramatic overhang is, to shield ourselves from the sun,” he says. “The sun drove the location of a lot to the rooms.”

In fact, the architect envisioned the entire project as a light-filled, community living room. “We wanted to create a place where everyone could congregate and gather, almost like a big house party,” he says.

His precedents? Old Lake Tahoe estates like the 1935 Thunderbird Lodge built by George Whittell, Jr. and designed by Frederic J. DeLongchamps, Nevada’s state architect at the time. It’s one of the last and best examples of grand residential estates built on the lake by prominent San Francisco society.

This clubhouse though, is thoroughly modern throughout. “It came from the great estates, but it looks forward as well as backwards,” he says.

He wanted more than just a private club and restaurant, but a place where people can gather year-round. “In the design and siting of the building there was the understanding of the sun that creates warmth in winter and shade in summer,” he says. “You cozy up to the fire in winter and wear flip-flops in summer.”

That created a building that’s a wide-open pavilion when it’s warm outside, but cozy and comfortable when it’s cold. “We think of a building as not what it looks like from the outside but how it functions inside,” he says. “It’s the flow that brings it together.”

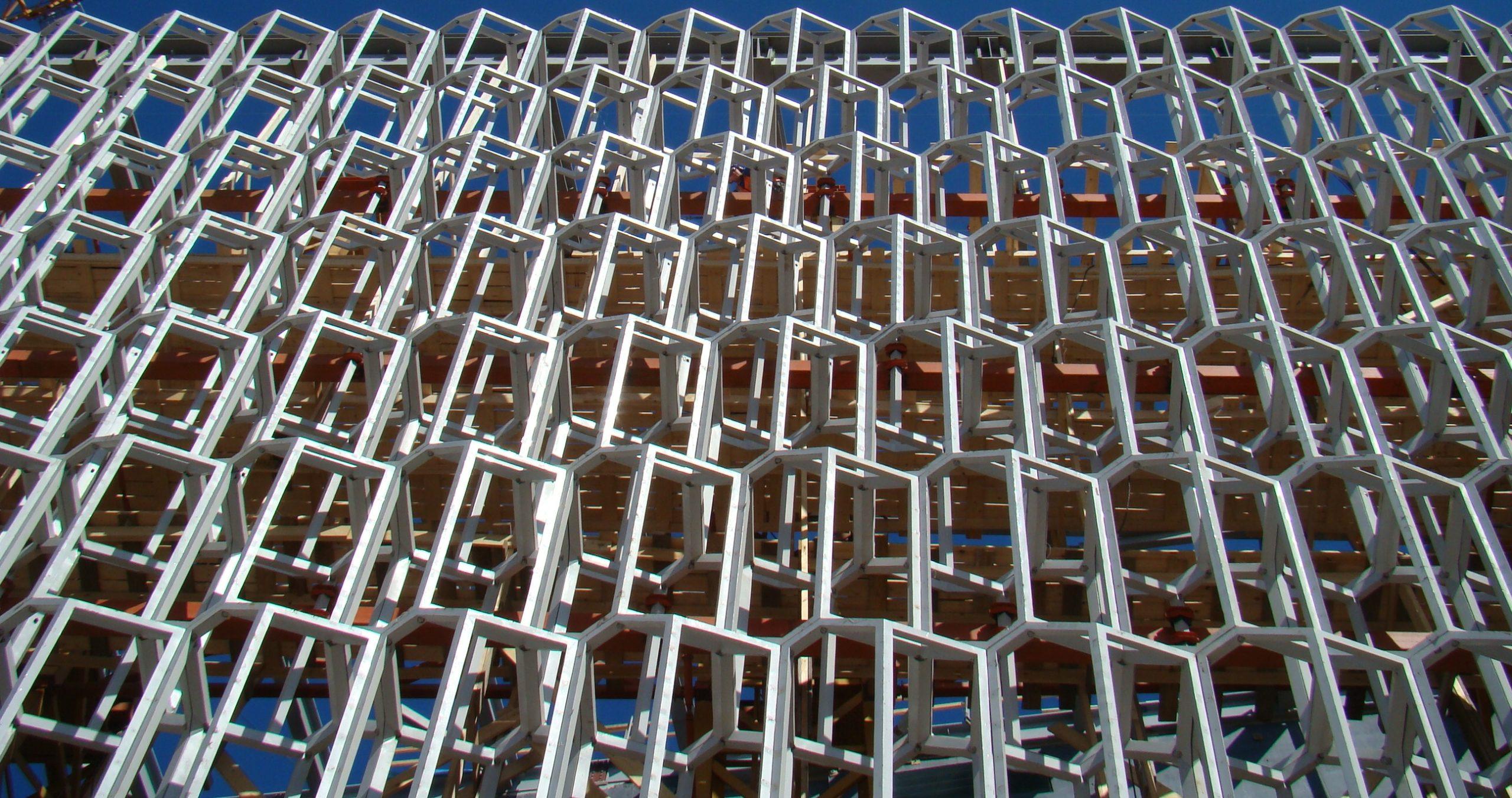

He used the tools of shade and shadow as part of his architecture, as the sun tracks across the sky daily. He framed the views of mountains on the west side of the lake. And because he wanted a building that expressed strength, he created broad overhangs, stout beams, and columns supporting the mass of its roof, steeply peaked for the snow load.

“We knew it had to be storied because it’s a small site to capture space,” he says. “The second level is where most of the building lives and has the best views.”

Rather than a single door, he designed multiple entries to blur the line between inside and out. “It’s not just: ‘Let’s have a front door and walk in’ – it’s much more welcoming than that,” he says. “It’s a friendly building – you drive up and a fire pit greets you,” he says.

This is a building that’s truly engaged with its surroundings, with local granite and timber, and restraint in its placement of glass. “There’s glass but there’s a minimized reflection so if you’re out boating there’s no glare,” he says. There’s an evergreen tree screen to mitigate that.”

Most importantly, though, this is a place to socialize, make new friends, and spend all day. “You can exercise, have meetings, or use the residential component for extra guests,” he says. “There’s great food, and then there’s the idea you could come down, and have a quick cup of coffee in morning. All these aspects come together in a great stew.”

As for context, it’s surrounded by nature, not structures – and so it’s scaled down to the human experience.

Its site and design may be driven by the sun – but its function and form are all about the people it serves.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2305]