Back in the 1970s, New York architectural historian Mosette Broderick hit the motherlode of municipal records.

It consisted of the New York City docket books from 1866-67 on, when construction documents were just beginning to be recorded. “Every time a builder went to get a permit, he had to write by hand where the location was, what the cost would be and who the architect was,” she says.

Seated in a dilapidated Tweed Courthouse, she pored over every page. It was a revelation at a time when most art historians were more interested in visual elements like architectural motifs and column orders.

“In reading the docket books I saw the city arise before me,” she says. “I could visualize it coming to life.”

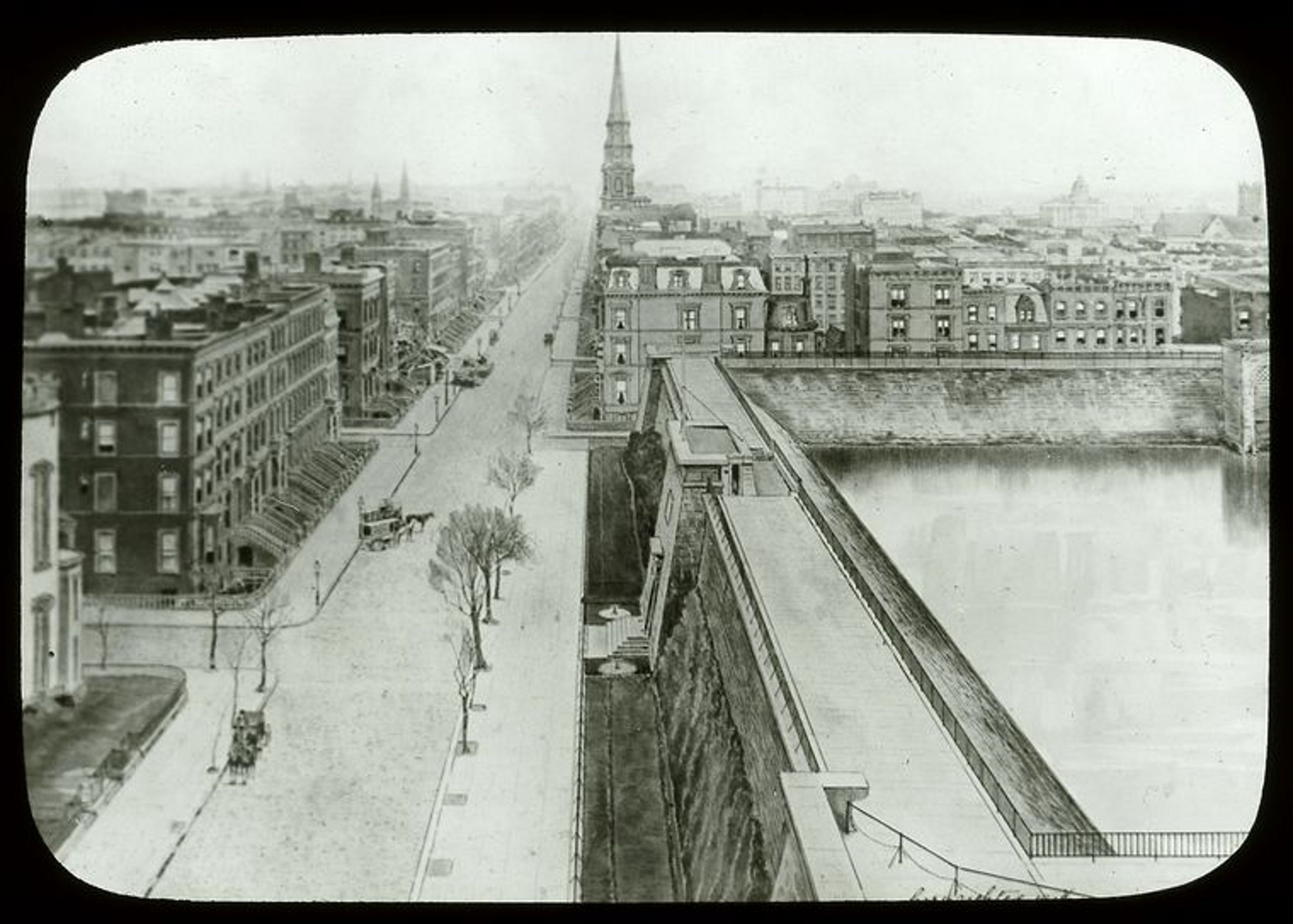

More specifically, she could witness the birth of Fifth Avenue – and its sumptuous mansions as they ballooned from Washington Square north to 95th Street. “The upper middle class and the rich were building north and farther north, like a turkey baster,” she says. “It fanned out to the back and west – it pulled New York City up.”

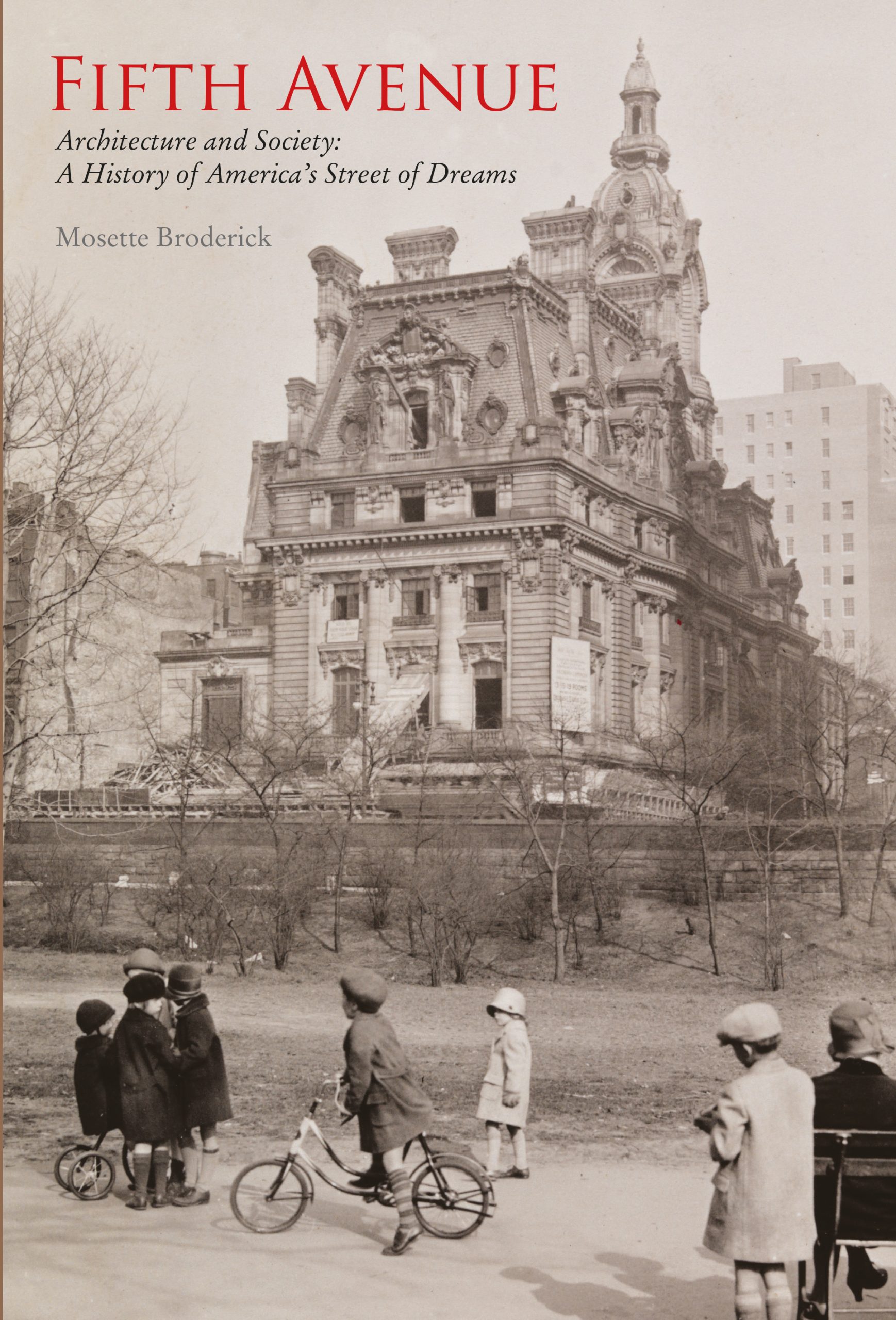

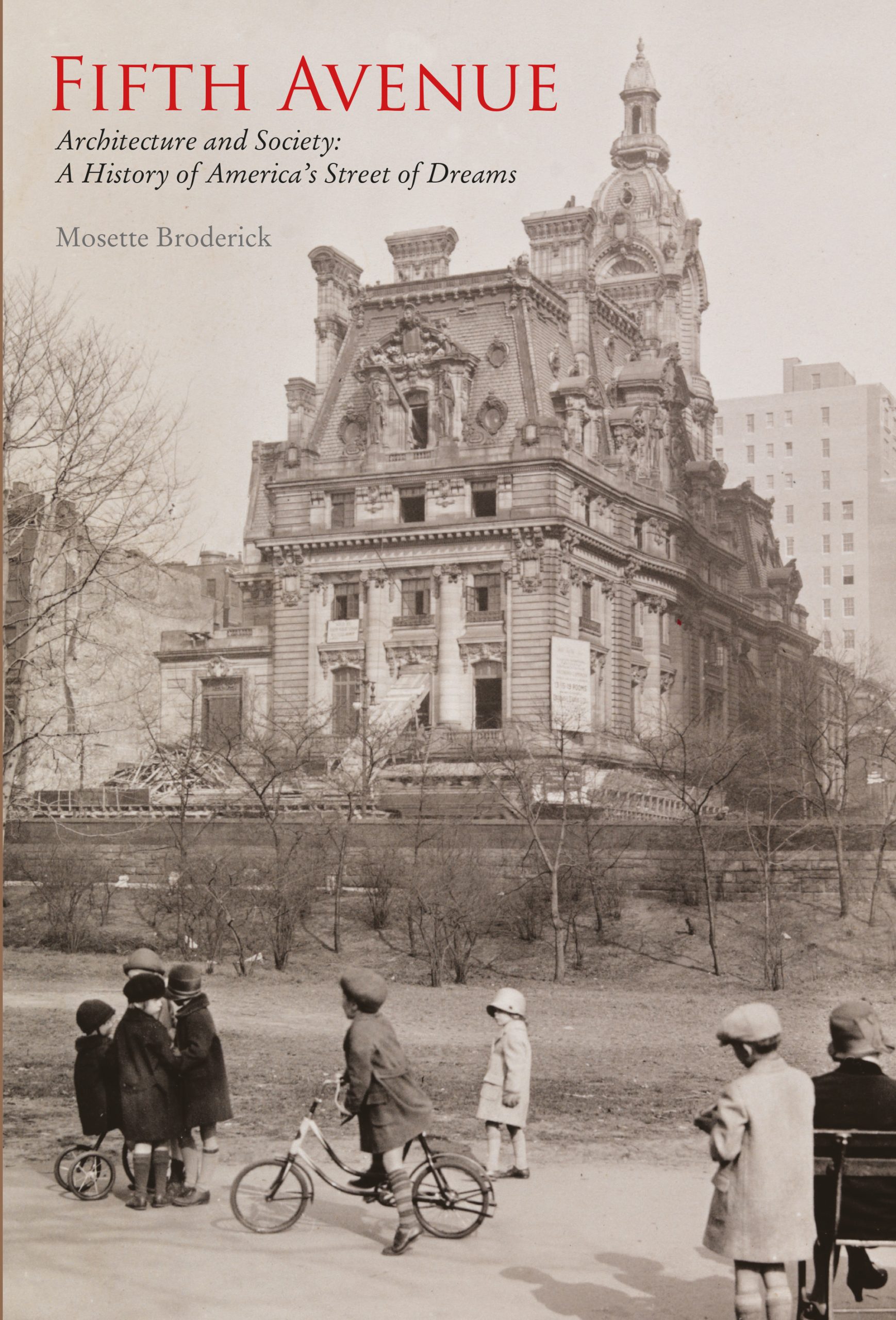

Decades later, after penning books on the Villard Houses and McKim, Mead & White, she’s authored a new one on the rise and fall of those mansions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It’s called “Fifth Avenue: History of America’s Street of Dreams,” and it’s available now.

These were no ordinary mansions. They were social and business vehicles for the upwardly mobile, like today’s yachts tied up in Nantucket or the Ferraris displayed at “Cars on Fifth” in Naples.

But on 19th-century New York’s Fifth Avenue, the mansion was the desired status symbol. “Businessmen didn’t trust anyone, and did all their business in their house where they trusted only the family, like Commodore Vanderbilt” she says. “The family and house were their centers of projection of success in family and business.”

Eventually, business districts and financial centers like Wall Street would draw the men of the house downtown to work. That left the women at home with new conveniences and immigrant servants “Now there was social prestige – and the societal dreams of the wife,” she says. “Someone like Alva Vanderbilt could have built a normal house, sure, but she wanted to make a statement.”

Aided by architect Richard Morris Hunt, she did exactly that with her Petit Chateaux on the northwest corner of Fifth and 52nd. It was three and a half stories tall, a blend of French Gothic and Beaux Arts styles and took up the entire block. Alva hosted a costume ball for 1,200 invited guests there in March, 1883 – and cemented her position in late 19th-century New York.

The competition? Up until then, it had been mostly the early 19th-century Stuyvestants and Knickerbockers who’d intermarried, joined the Episcopal Church and shifted New York’s language from Dutch to English. But Alva, her new mansion and her compatriots would leave them looking.

Instead of wanting to fit in, women like Alva wanted to break away and show off with the most glamorous houses ever seen. “Marietta Stevens and Alva forced society to accept them by turning to Europe and establishing themselves as an American aristocracy like England’s,” she says. “It was a shoehorn to get into New York society.”

Hunt would design only a handful of Fifth Avenue mansions. From the 1840s to the 1890s, most were designed by speculative builders. One exception was Austrian architect Deklas Lineau, who’d spent time in Paris and arrived in New York in 1848, landing a number of large commissions on lower Fifth Avenue.

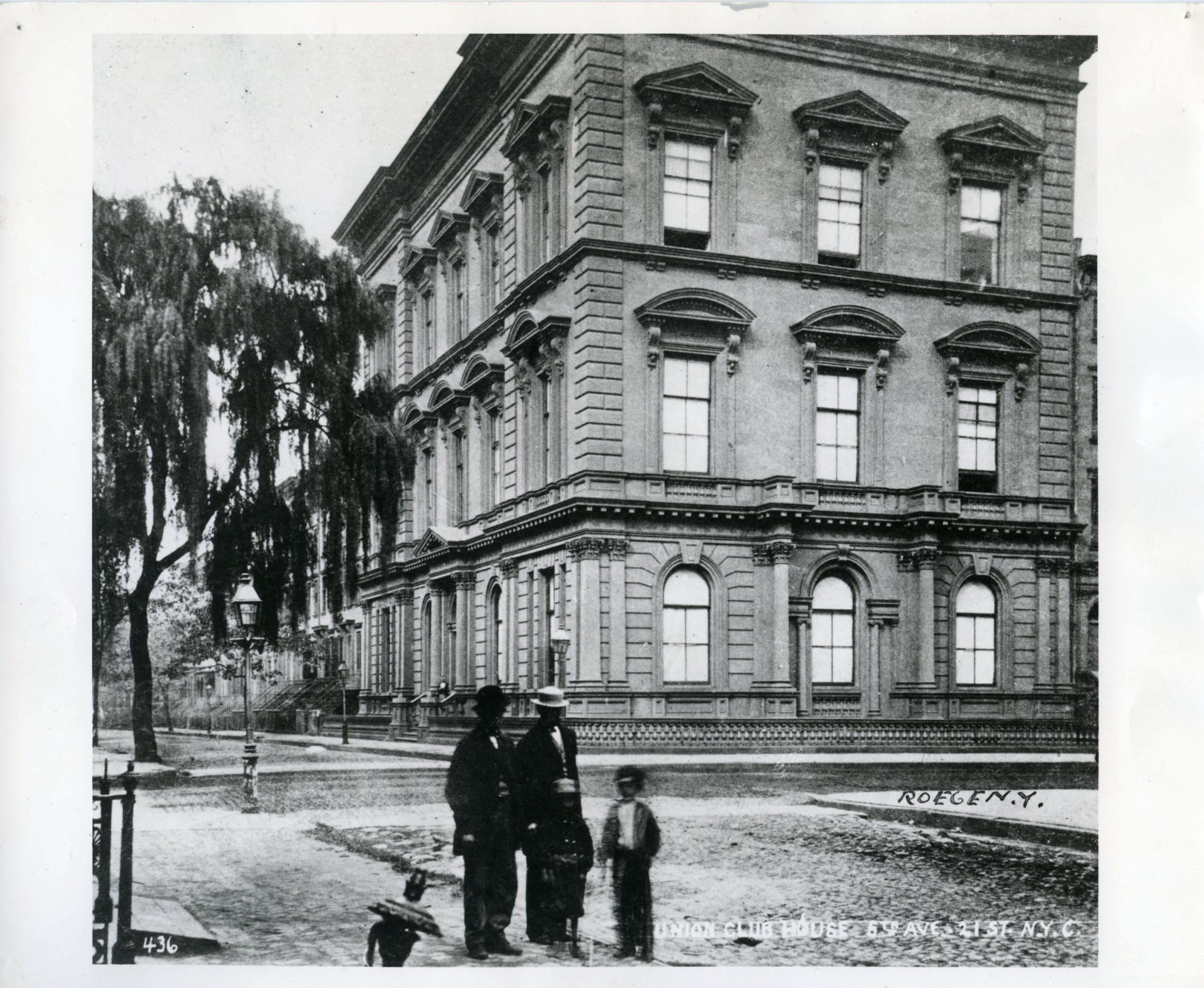

Englishman Griffith Thomas was the most prominent architect in the 1850s, though he was a builder by training. “He produced the brownstone type that you see everywhere,” she says. “He was also building in the Garment District and did the Union Club Building.”

By 1897, C. P. R. Gilbert was designing a sophisticated mansion in the late Medieval style on 79th Street for Isaac Fletcher. And philanthropist Frieda Schiff Warburg wanted one too – so by 1908, Gilbert had built it for her and her family. Located at Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street, it now houses the Jewish Museum.

Some have estimated the number of mansions to be as high as 400; actually it was about 182. But by the 1920s, almost all the mansions were demolished. One still stands in lower Manhattan as the Salmagundi Club. The Duke House is now the Institute of Fine Arts; both the Andrew Carnegie House on 91st, and Willard Straight’s mansion on East 94th have survived.

The big surprise is how short these mansions’ lifespans were. The cover of Broderick’s new book shows one being pulled down, rather than going up, in 1927. “Most were primarily accessed for 20 years by families, who then moved uptown or died – and then all were gone,” she says.

But not forgotten. In this book, she’s saved the images and the stories that bring them back to life.

For more, go here.

![[St. Luke's Hospital.]](https://architectsandartisans.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Chapter-11_St.-Lukes-Hospital_X2010.11.4761_MCNY-scaled.jpg)

![[Cornelius Vanderbilt's residence.]](https://architectsandartisans.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Chapter-11_Cornelius-Vanderbilt-House_X2010.11.4828_MCNY-1-scaled.jpg)

![[54th Street and 5th Avenue.]](https://architectsandartisans.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Chapter-10_Looking-West-from-St.-Lukes-Hospital_x2010.11.14182_MCNY-scaled.jpg)