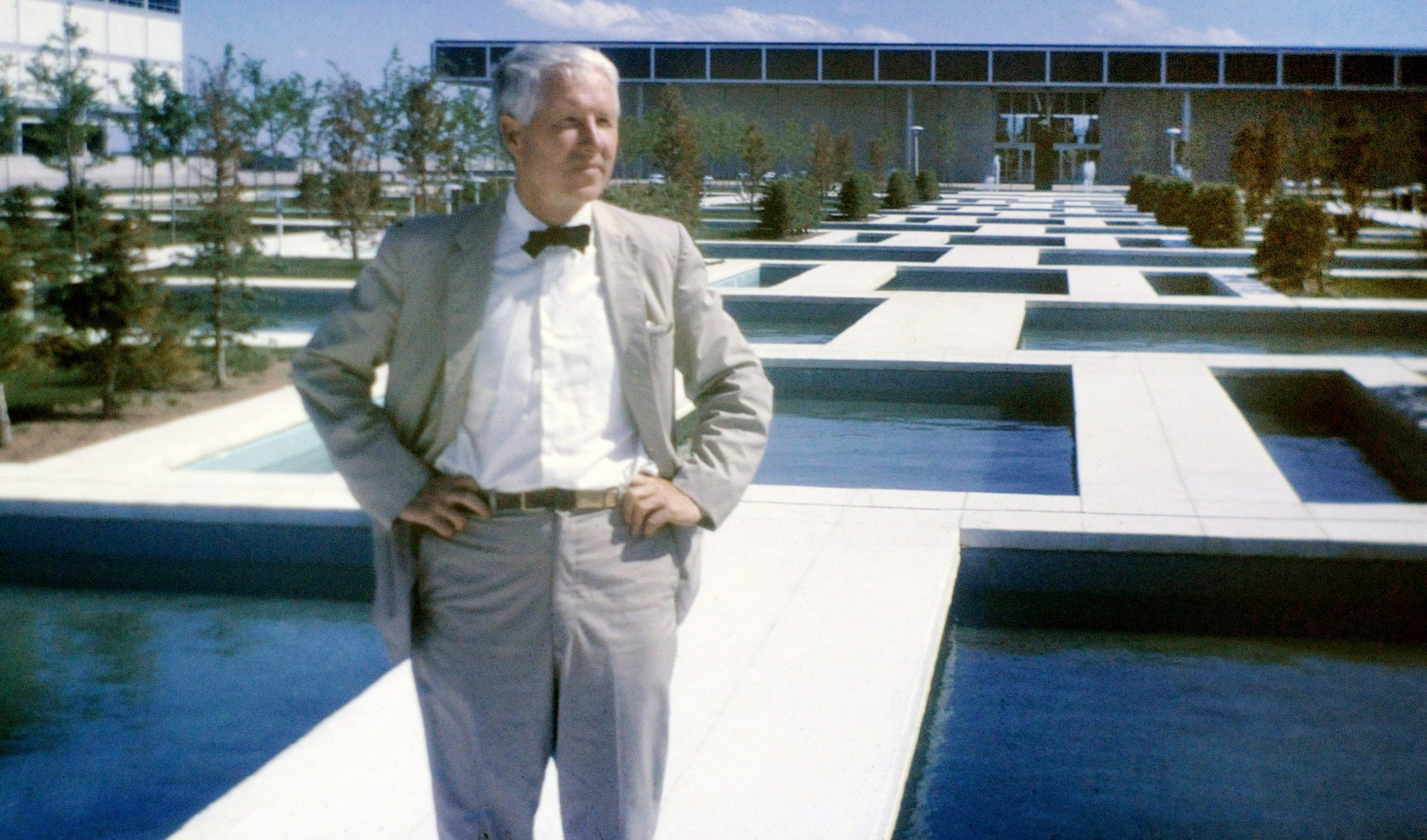

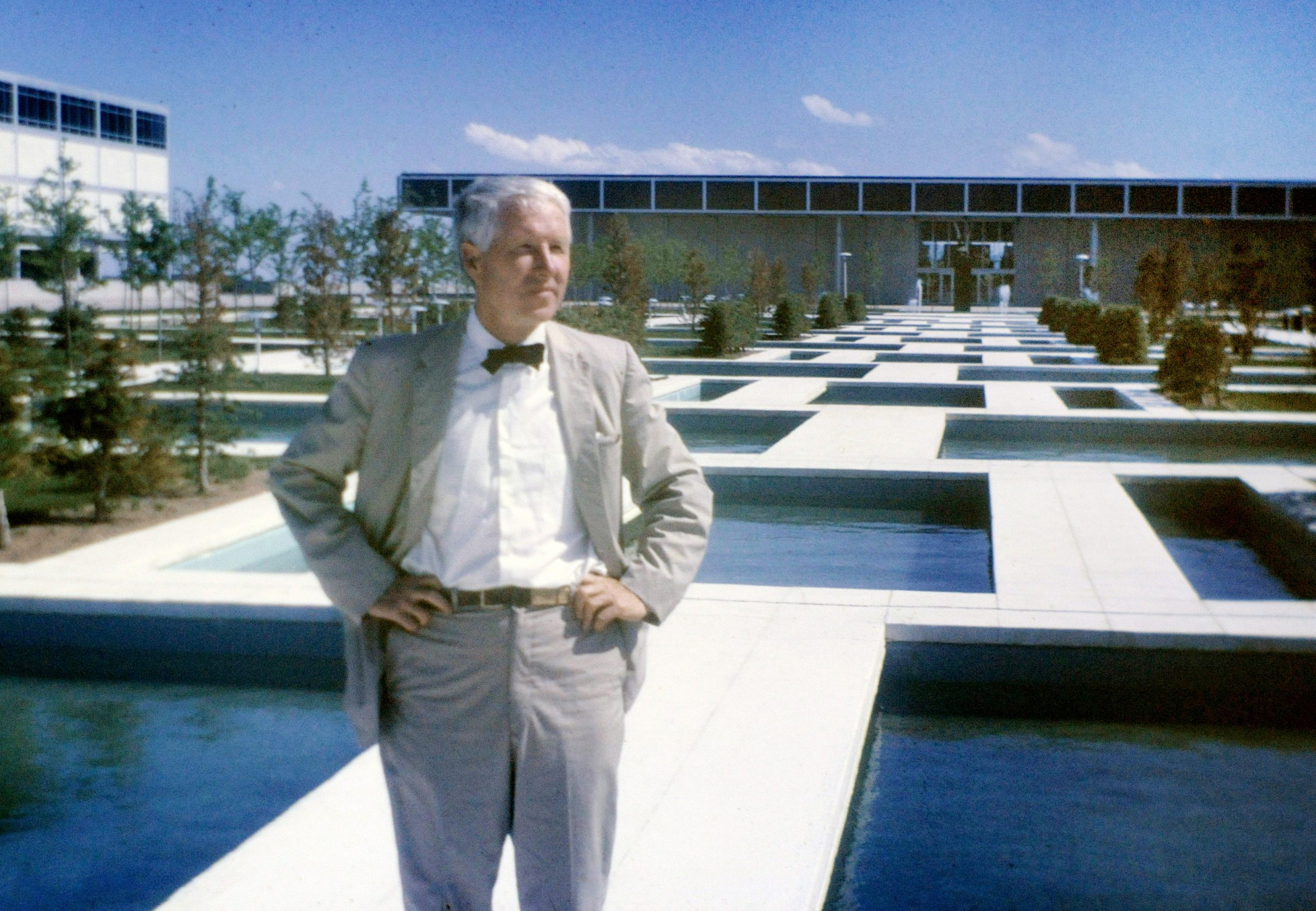

A traveling photographic exhibition of legendary landscape architect Dan Kiley is set to open on January 18 at The Exhibition Space @ABC Stone in Brooklyn. (Opening reception details can be found here).

The show was organized by the Cultural Landscape Foundation in 2013, on the centennial of the late modernist’s birth.

“This the 21st location for the exhibition and the only time the the full exhibitions’s been in New York City,” says Charles Birnbaum, founder, president and CEO of the foundation. “This includes the addition a half-dozen video clips, with former employees, to the original exhibition”

Kiley was known for working with some of the great modernists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including Eero Saarinen, Kevin Roche and I. M. Pei. His widely acclaimed landscape architecture at Lincoln Center has been largely erased. The exhibition is designed to honor Kiley and his legacy while calling attention to the need for informed and effective stewardship of his work and, by extension, modernist landscape design.

“We did the exhibition as part of our Landslide education and advocacy program – Kiley’s designs, which can pose maintenance challenges – include grids that are inspired by French formal gardens,” he says. “Changes in plans or maintenance of a project can diminish it.”

Not so with the 2019 Ford Foundation Atrium restoration in Manhattan, by Gensler and Raymond Jungles. “That rehabilitation was incredibly thoughtful and sensitive,” he says. “It set a high bar.”

Among Kiley’s other significant works of modernism include landscape projects at The St. Louis Arch, the South Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Dallas Museum of Art. Fountain Place in Dallas was a seminal work of Postmodernism with I.M. Pei, and features 200 floating bald cypresses in water. “Then there’s the Miller Garden in Columbus, Indiana, where you can see the mature design intent,” he says.

In 1953, Cummins Inc. CEO Irwin Miller had commissioned Saarinen as architect for his home, Alexander Girard as its interior designer and Kiley as landscape architect for its garden. A few years later, when Miller established the Cummins Foundation Architecture Program, he created a list of 12 architects to design churches, banks, firehouses and businesses across Columbus.

His choice for design in the environment, however, was laser-focused. “His list of landscape architects only had Kiley’s name on it,” Birnbaum says. “I joke that Columbus, Indiana is ‘Kileyville’ because the great majority of landscape architecture there is his.”

Kiley was a modernist who recognized that landscape was an extension of a building’s architecture – and vice versa. Nowhere is that more evident than at the Cummins corporate headquarters in Columbus, designed by Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Architects. There, Kiley worked on a huge scale, but didn’t forget the human element.

“The massive pergola at the Cummins headquarters building is monumental – a great, celebrated work of classical architecture, but a modern design with a grid of pavers and laden with vines,” he says. “He takes something monumental and brings it down to human scale and provides shade in summer months.”

Second only to Frederick Law Olmsted in terms of National Historic Landmark designations, Kiley died in 2004 at the age of 90. And his legacy lies not just in his built work or clarity of design, but in those who followed him.

The Kiley renaissance began in 1978 when Peter Walker mounted an exhibition of newly commissioned photographs by Alan Ward of the Miller Garden. Walker stated at the time that the Miller Garden was “where modernism began.” A next generation of landscape architects that studied under Walker including Andrea Cochran, Gary Hilderbrand and Doug Reed, to name a few, who continue to carry that torch for clean, restrained minimalism, often with grids,” he says.

The exhibition at 189 Banker Street runs through April 30, 2024 and is free and open by appointment, Monday-Friday, between 9:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M.

For more, go here.