While much has been written about the life and the innovative organic architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, little scholarly attention has focused on Wright’s third wife, Olgivanna, the individual who sparked a renaissance in Wright’s career from the time of the couple’s first meeting in1924. There’s a new book about her out from ORO Press, by Maxine Fawcett-Yeske and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, and A+A recently interviewed Fawcett-Yeske via email:

Who was Olgivanna and why was she important?

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, third wife of America’s innovative architect, not only sparked a renaissance in her husband’s career but possessed a creative spirit distinctly her own.

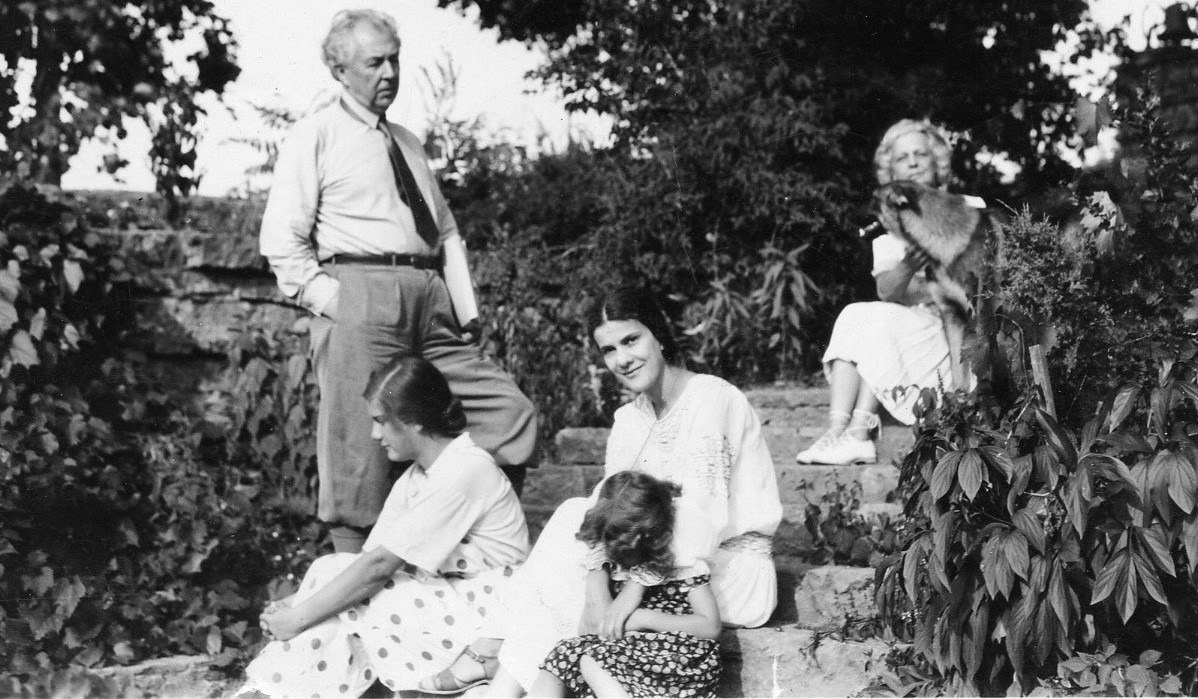

Olgivanna Milijanov Lazovich Hinzenberg met Frank at a ballet performance in Chicago in 1924. While it was love at first sight, it was four years before the two could marry as both were seeking divorces at the time of their meeting. In their life together, Olgivanna created an environment in which Frank could flourish. Inspired by her love and worldliness and steadied by Olgivanna’s practicality and resourcefulness, Frank imagined some of his most breathtaking designs, from Fallingwater to the Guggenheim Museum. It was through Olgivanna’s creative genius that the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, also known as the Taliesin Fellowship, was formed. It was a school of architecture like no other. Apprentices “learned by doing,” working alongside Mr. Wright and realizing many of the designs that came out of this collaboration. Olgivanna oversaw all administrative aspects of the school as well as the holistic curriculum that, in addition to architectural design, taught apprentices about the arts, public speaking, etiquette and decorum, and much more. Mrs. Wright was also an author and composer. She wrote five books on philosophy and about the life she and Frank shared. She composed over forty musical compositions that enriched the lives of the apprentices as well as audiences who came to the music and dance festivals at Taliesin in Wisconsin and at Taliesin West in Scottsdale. In many ways, Mrs. Wright was her own kind of architect—crafting melodies and sonorities deserving of recognition among the works of other composers of the mid-twentieth century. She was also an architect of the human spirit, an advocate of architectural apprentices for whom music, art, literature, dance and philosophy are “organic” and fundamental to the structural design of the mind, body, and character.

Her life before Wright?

Her full name was Olga Ivanovna “Olgivanna” Milijanov Lazovich Hinzenberg Lloyd Wright. She was born in Cetinje, then the capital of the small principality of Montenegro. Her father, Iovan Lazovich, was the first chief justice of the Montenegrin Supreme Court. Her mother was a general in the Montenegrin Army. Olgivanna’s mother, Melitza, was the daughter of Duke Marco Milijanov (1833-1901), a general credited with preserving Montenegro’s independence from Turkish rule in 1878. Melitza was the youngest of three daughters of the Duke. In the absence of any sons, Milijanov took Melitza into the army and trained her as a soldier. Thus Olgivanna came from a strong and diverse aristocratic background—a mother skilled in social rebellion and military tactics and a father dedicated to peace and justice.

Olgivanna’s father had gone blind by the time of her birth, so during her early childhood in Montenegro, Olgivanna served as the eyes of her father. She read everything to him—newspapers, legal documents, books on poetry and philosophy, at the same time developing a worldview of her own that was far advanced for her years.

At the age of nine, Olgivanna went to Russia to begin more formal schooling. She lived with her sister Julia (who was studying to be a physician at that time). Julia was married to Russian nobleman Constantin Siberiakov, whose family owned gold mines in the Ural Mountains.

At the age of 20, Olgivanna married Russian architect Vlademar Hinzenberg. Also while in Russia, Olgivanna was introduced to Greco-Armenian mystic and philosopher, Georgi Gurdjieff, with whom she studied for several years. In 1917, at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution, Olgivanna fled Russia along with Gurdjieff and his followers. During that same eventful year, Olgivanna’s daughter with Hinzenberg, Svetlana, was born.

Olgivanna lived for a time in Tiflis, in Georgia near the border of Turkey, along with Gurdjieff and his followers. After several other sojourns, the group finally established the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Avon, France at Fontainebleau in 1922. Gurdjieff believed in developing the “complete person”—mind, heart, and body. His curriculum was holistic and strict, incorporating dance, exercise, personal hardship, physical labor, and psychological discipline. Olgivanna remained a loyal student, and under Gurdjieff’s tutelage, she acquired basic skills she had not learned in her privileged upbringing. She did laundry, cooked, painted and repaired the Study House, fed the livestock and cleaned the barn, and in the evenings assisted with teaching the dance movements that were central to the development of each pupil’s self-awareness. As word of Gurdjieff’s teaching spread, many individuals came to the Institute for personal growth and healing. When writer Katherine Mansfield, suffering from the later stages of tuberculosis, arrived at the Institute, Gurdjieff assigned Olgivanna to look after her. Indeed Mansfield’s final days were spent in the care of Olgivanna Hinzenberg. When Gurdjieff finally deemed it time for Olgivanna to go out into the world on her own, she emerged as a dancer, musician, educator, and philosopher in her own right.

Her life with Wright?

Much of the previous writing about Olgivanna and Frank’s lives focuses on the tumult of the years when Frank was seeking his divorce from Miriam Noel, while other sources underscore the unique aspects of the Taliesin Fellowship and the apprenticeship experience.

One of my favorite stories from the autobiography is about the bi-annual migration of the Wrights and the apprentices between Spring Green, Wisconsin, and Scottsdale, Arizona. After a long and exhausting drive that on one particular trip took the entourage to the Grand Canyon for some sightseeing, the Wrights stopped, well after dark, to camp for the night. Upon rising the next morning at sunrise, Frank called to Olgivanna, “Get up and look!” “I leaped out of bed, throwing a blanket over my shoulders, and as I stood beside him I saw to my horror that we had laid our sleeping bags no more than four feet from a sheer drop-off of the Grand Canyon. If we had driven our cars a few yards further . . . a terrible thought. We had been so tired the night before that we had done no exploring, and did not notice the precipice that plunged more than a mile down into the Colorado River. We look cautiously over the edge. Far beneath us the river wound like a gray snake. We quietly put on our warm, heavy clothes and sat down by the blazing breakfast fire. The sun was rising now above those prehistoric rock-hewn plateaus and the colors unfolded over the canyon in fantastic beauty.” “After all,” my husband said, “this is what we came for. And it was all worth it.”

Life was never boring for Frank and Olgivanna. They seemed always to be on the brink of some new and exciting adventure.

Her life after Wright?

The death of her husband on April 9, 1959, left Olgivanna with complete responsibility for the business operation of the Taliesin Fellowship. Meanwhile, her music began to pour forth, page after page. In addition, Mrs. Wright maintained a demanding schedule of speaking engagements— speaking across the globe about her husband and his concept of “organic architecture.” After many years of indefatigably keeping her husband’s name alive, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright died on March 1, 1985.

Your inspiration for the book?

I initially came to know of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright through her music. An avid admirer of Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture, I was pleased to have the time during a trip to Phoenix in June of 2003 to tour the Wright’s home at Taliesin West in Scottsdale. At one point, while the tour was in the kiva, the guide mentioned that we were going to watch a brief video about Mr. Wright’s signature “destruction of the box,” Wright’s affinity for dissolving the corners in room design to create more openness. The tour guide mentioned in passing that the music we would hear on the video was composed by Frank’s wife. As a musicologist my interest was piqued. While the excerpt we watched was very brief, what I heard was this highly expressive cello solo, subsequently surrounded by rich orchestration. I was determined to find out more about the woman who had composed this music. In the months that passed, I corresponded with Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the Director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, and, as it turned out, the person who worked closely with Mrs. Wright in her musical endeavors. As I learned more about Mrs. Wright’s music and began to transcribe the works from their manuscript form, over forty compositions comprised of chamber music as well as dance dramas the length of full-scale operas, I became more and more engrossed in the life experiences that fostered these intriguing compositions. Exploring the life of Mrs. Wright inspired my two trips to Montenegro where Olgivanna spent her early childhood and where her parents and grandparents had played significant roles in the history of this small Balkan country. Later, during one of my research trips to the Frank Lloyd Wright Archive at Taliesin West, I discovered from Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer that Olgivanna had actually written an autobiography, rough, unpublished, and read by very few people at that time. As Bruce and I discussed the autobiography, it became clear to me that before I prepare selected works editions of Olgivanna’s compositions and before I write Mrs. Wright’s biography, her words should be allowed to speak for themselves. So began the work of compiling and editing what would become Crna Gora to Taliesin, From the Black Mountain to the Shining Brow: The Life of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright.

The intent of the book?

The intent of the book is to give voice to Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, to allow her narrative to speak for itself, and to reveal the many dimensions and accomplishments of this remarkable woman.

What do you want the reader to do, think, feel after reading it? Why?

The reader will definitely laugh and cry along with Olgivanna as she tells her story. Remarkable in her tenacity, resourcefulness, and undeniable strength, her life was lived to the fullest extent.

[slideshow id=1827]