Now that a newly renamed Arthur Ashe Boulevard bisects Richmond’s Monument Avenue precisely where a three-story-tall statue of Stonewall Jackson is mounted on an outsized “Little Sorrel,” tongues are wagging around the nation – thanks to the The New York Times and The Washington Post.

After more than a century of adulation and silence about five Confederates overlooking the urban fabric from that City Beautiful-era promenade, local discussions actually are taking place.

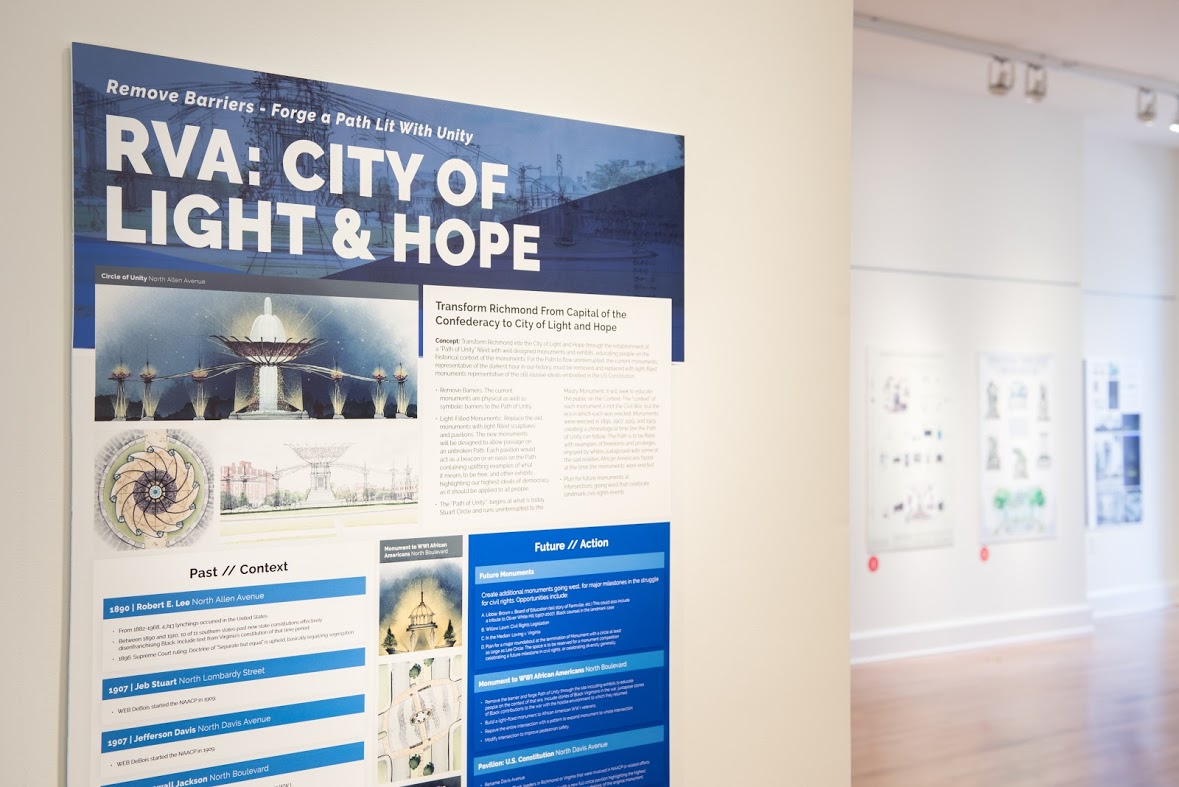

Leading the charge is Richmond’s Valentine Museum, which opened an exhibition called “Monument Avenue: General Demotion/General Devotion” in February. It’s the culmination of a conceptual competition that generated 70 responses from national and international artists, planners, designers and architects.

“The assignment was to re-imagine the entire 5.4 miles of Monument Avenue, including the mile from Jeb Stuart, the first monument, to Arthur Ashe, the last,” says architect and organizer Camden Whitehead, associate professor of interior design at Virginia Commonwealth University. “The idea was to look at what the options might be and how to deal with things precious to some and offensive to others.”

One entry suggests burying the statues and leaving only heads visible, to eliminate opulence and allow people to see the figures at eye-level. Another wants to replace all Confederate statues with light-filled sculptures and pavilions to create new monuments celebrating major milestones in the civil-rights movement.

All are intended to begin a lengthy process of discussion. “It took 20 or 30 years for the older monuments to be built, and discussion has been going on for a long time now, and it’s not going to be resolved overnight,” he says. “We’re trying to develop civil habits that will allow us to talk about difficult subjects.”

They’re not the only monuments in the city, to be sure. There’s A.P. Hill on Northside and Harry Byrd on the Capitol Grounds, not far from Washington surrounded by his Praetorian Guard.

But this exhibition is looking hard at five Confederates who mean different things to different people. “It’s not directly challenging Monument Avenue, but challenging people to think about the monuments,” he says. ”It’s an opportunity to see how others view Richmond and Monument Avenue.”

And to talk about it while listening carefully – and realize that a pedestal is a poor place for taking the measure of a man.

For more, go here.

[slideshow id=2061]